The Weekly Anthropocene Interviews: Bill McKibben, Climate Activist Extraordinaire

Bill McKibben has been called “one of the world’s leading environmentalists,” “lion of the climate movement,” and “a living legend in environmental activism.” Among many other accomplishments, he has written the first major general-audiences book on climate change in 1989 (and more than 15 other books since), founded global grassroots climate activist network 350.org in 2007, spearheaded the movement that convinced President Obama to block the Keystone XL pipeline in 2015, worked closely with the Bernie Sanders campaign and eventually co-wrote the Democratic Party platform in 2016, and founded Third Act, a seniors-led climate action group, in 2021.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Mr. McKibben’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

There are so many things I want to talk to you about. Let’s start with this one: you wrote a great Mother Jones article about how the environmental movement needs to switch from saying “No” to saying “Yes,” to move from an oppositional "NIMBY" framework to supporting widespread new renewables development. Can you tell me more about that?

I was writing more aimed at people like me, old white guys who have been pretty good at using the system to stop things, and trying to come up with some principles for learning when it’s appropriate to let things go instead. It’s clear that people are going to object sometimes to solar panels or wind turbines. I think that they should first think about questions like, “If it’s not in my backyard, whose backyard is going to get wrecked by climate change?”

“It’s clear that people are going to object sometimes to solar panels or wind turbines. I think that they should first think about questions like, “If it’s not in my backyard, whose backyard is going to get wrecked by climate change?”

-Bill McKibben

Because, as you know, climate change is not only dangerous, it's one of the most unfair things we've ever done, and the burden has fallen mostly on people in other parts of the world who haven't done much to cause it. We also have to think about the temporal debt we owe. People like me have been putting carbon in the atmosphere for many, many decades, and it’s all still up there, so even if you bought a Tesla now it doesn’t absolve you of the debt that you owe.

I think there’s a good argument for being enthusiastic whenever we can about the possibility of putting up solar panels and wind turbines and so on, and maybe even learning to think of them as beautiful.

This doesn’t mean we should demand that people who’ve been screwed over the years get screwed some more. I have great sympathy for indigenous groups and frontline communities that have taken it on the chin from the fossil fuel era, and it strikes me that if they’re wary of renewable energy development, we should be able to listen to that and hear it.

That is really interesting. Because there’s increasingly this weird shift happening where we’re seeing the traditional bad guys of the environmental movement, like big multi-national corporations, wanting to build renewable energy, and scrappy grassroots opposition groups who have historically been the good guys opposing renewable projects and sometimes seriously slowing down decarbonization.

Like in Nevada, there was the Battle Born Solar Project, which would have been 850 megawatts of clean power, and it was shut down by a coalition of local and environmental groups who opposed it. And as a young person who is concerned about climate change, and who really has loved the environmental movement since childhood, that feels like a betrayal to have people who call themselves environmentalists opposing solar and wind energy that is really critical for the future of the world.

And so I was really happy to hear you, such a respected figure among environmentalists, call out this attitude and say, Yes, we really do need solar and wind. So what are your thoughts on how some of the traditional sort of dynamics have flipped a little bit? Like in many places renewable energy is now Goliath, and it feels right to support David against Goliath. But in this case we actually really do need the big energy projects.

I think that one of the things we can learn from looking at the rest of the world is that this often works better if, to the degree we can, we give local people some ownership and control over some of those assets. it really helps.

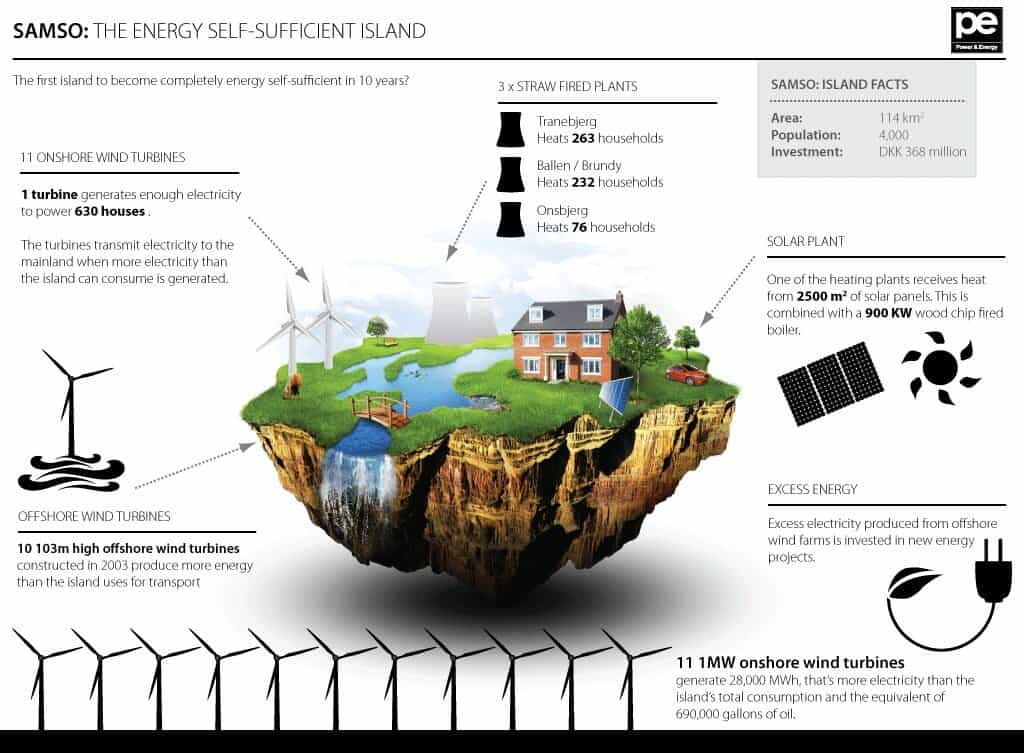

You know, I just spent a day with a guy who did that remarkable development on Samsø Island in Denmark over ten years, which became one of the first fully renewable places on the planet about a decade ago. And he kept stressing how much easier it was because the ownership of the turbines and things they were building was at least in part owned by people in the community, who had shares in them and things. I think there's even been research done to show that people report less health effects from wind development if they’re part-owners of the thing. Community ownership is a thing that would be really helpful in speeding up this process.

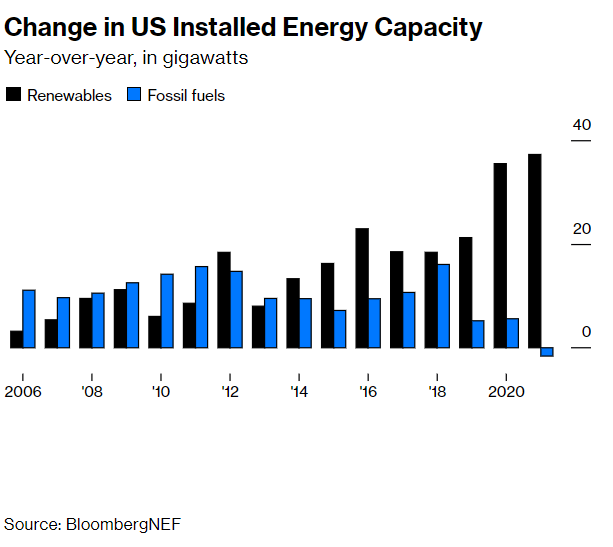

There's some unprecedented, amazing climate progress happening at the national level. Like with the Inflation Reduction Act, and 92% of new electricity-generating capacity added in India in 2022 being solar and wind, and solar and wind overtaking all fossil fuel energy in the European Union in May 2023 in terms of electricity produced.

But the international climate talks, many of which you visited and called out for this, seem increasingly “industry captured,” with Sultan Al Jaber, an oil company executive and dynast from an absolute monarchy, set to helm the upcoming COP28 climate talks. Which, as you pointed out, is kind of a travesty. So what do you think of this sort of bifurcation, with unprecedented progress on the national/supranational level in the US and EU and India, and yet fossil fuels seeming to entrench themselves at the international talks?

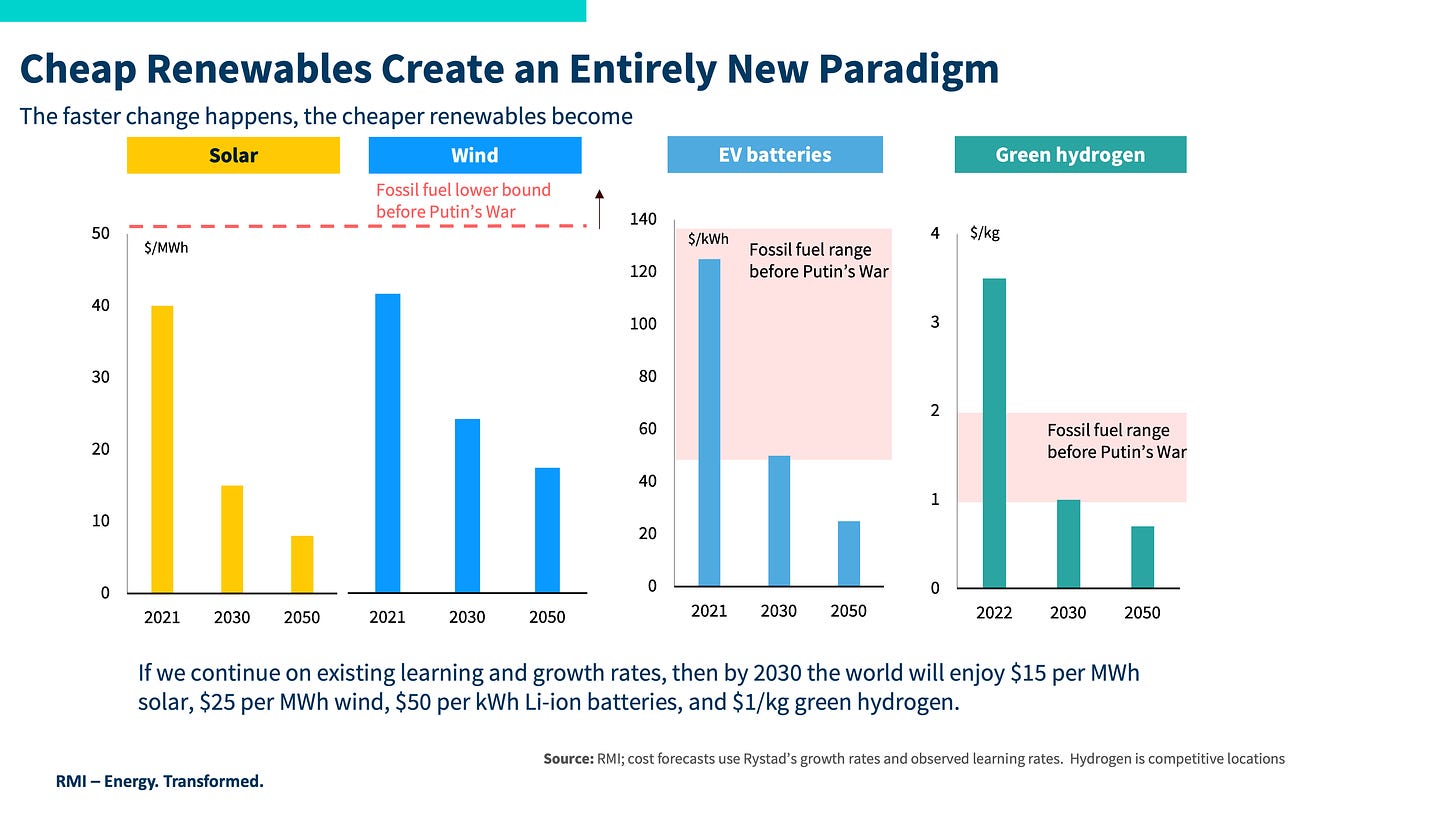

I think what's going on is the fossil fuel industry knows that it's at now a technological disadvantage. There are cheaper, cleaner ways to produce the same product that they produce. And that's a huge threat to them because they have tens of trillions of dollars worth of reserves that they may never get the chance to exploit. So what they're doing is playing the card that they're good at. They have built up enormous political power over many decades of being the most important industrial force in the world. So now they're relying on that political power to compensate for the fact that they've got a crappy product. That's what's going on all over the place. That explains Joe Manchin. And that explains Sultan Al Jaber.

“The fossil fuel industry knows that it's at now a technological disadvantage. There are cheaper, cleaner ways to produce the same product that they produce…They have built up enormous political power over many decades of being the most important industrial force in the world. So now they're relying on that political power to compensate for the fact that they've got a crappy product.”

-Bill McKibben

Do you think the international climate talks will become irretrievably captured? Do you think we can look for any meaningful progress at all at COP28 given that there’s an oil executive at the helm?

My slightly cynical guess is that the high point of the UN process was Paris [the COP21 meeting in 2015 that produced the landmark Paris Accords on climate action]. And that accomplished most of what we were ever going to accomplish through the UN system. And now, at best, it's a job of trying to hold people to the promises they made there.

The international system is unwieldy, and easy for the fossil fuel industry to game, and it takes extraordinary amount of work to get it to produce something useful. We built up to that in 2015, that was the high-water mark. But since then, the international community has gotten less welcoming to this kind of work. There are far more autocracies than there were in 2015, and so global organizing gets harder and harder. I’m spending part of this week trying to get my old friend Hoang Thi Minh Hong from Vietnam out of jail. There’s huge parts of the world where it’s very hard to organize.

You mentioned autocracies. Some have called this moment a second cold war between democracy and autocracy, between, broadly speaking, China and Russia on one side, and the US, EU, UK, Japan, Canada, Australia, and other democracies on the other side. And some have argued that this second cold war dynamic, as threatening as it is geopolitically, might actually be good news for climate action, because it means that China and the US are now competing to decarbonize faster. You see [American] politicians saying that we can't let China dominate EVs and batteries. And that's part of what got the Inflation Reduction Act passed, which single-handedly brought about an American green manufacturing boom. So, what do you think about the idea that the prospect of a big superpower rivalry might actually be speeding up investment in climate action technology?

There may be some of that. And I think the other thing that's going on is, you know, Putin's insane war in Ukraine has really wised up the European Union that they're going to have to move much faster on decarbonization. If it continues to weaken one of the biggest oil barons in the world, Vladimir Putin, then that’ll be a useful thing too.

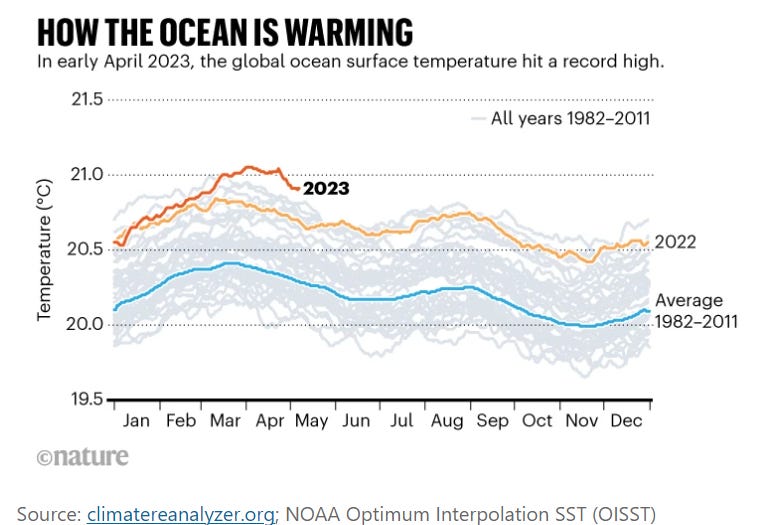

Absolutely. And building on what you said, I don’t quite know how to describe this, but both climate change disasters and climate action progress almost seem to be “fading into the foreground.” Clean energy investment is reshaping economies, climate consequences are impacting people’s lives from New York smog to European and Asian heatwaves to unprecedented ocean heat to the Panama Canal carrying less tonnage due to droughts. The Ukraine War and Europe’s decarbonization is a climate story. But even though climate change is in the news every day, it seems to have been…normalized. There was sort of a hope, for years, that there'd be some moment where people would wake up and go “Oh, my God! Climate change is here, we need to take action!” And I feel like climate change has been very clearly here for a while now, and it just seems be almost recognized without being recognized.

I think there's some truth in that. I also think that the next 18 months are going to be very intense, with the El Nino and the rapid rise in temperature. My guess is that it’s going to be so dramatic that they provide a real system shock. Perhaps the last one like that that we're going to get in a politically relevant time.

So this is a really tough one. But I've also noticed that there is a very difficult balance to strike as someone trying to be a climate communicator. Even as politicians and executives still underplay climate change, some people my age have almost overcorrected on climate change, and they say things like “civilization will fall before I can have kids.” Some people misinterpret the classic IPCC warning on trying to avoid 1.5 Celsius warming by 2030 as saying “the end of the world will come in 2030,” which is just not true. You hear about research on suicidal ideation among young people connected to climate change.

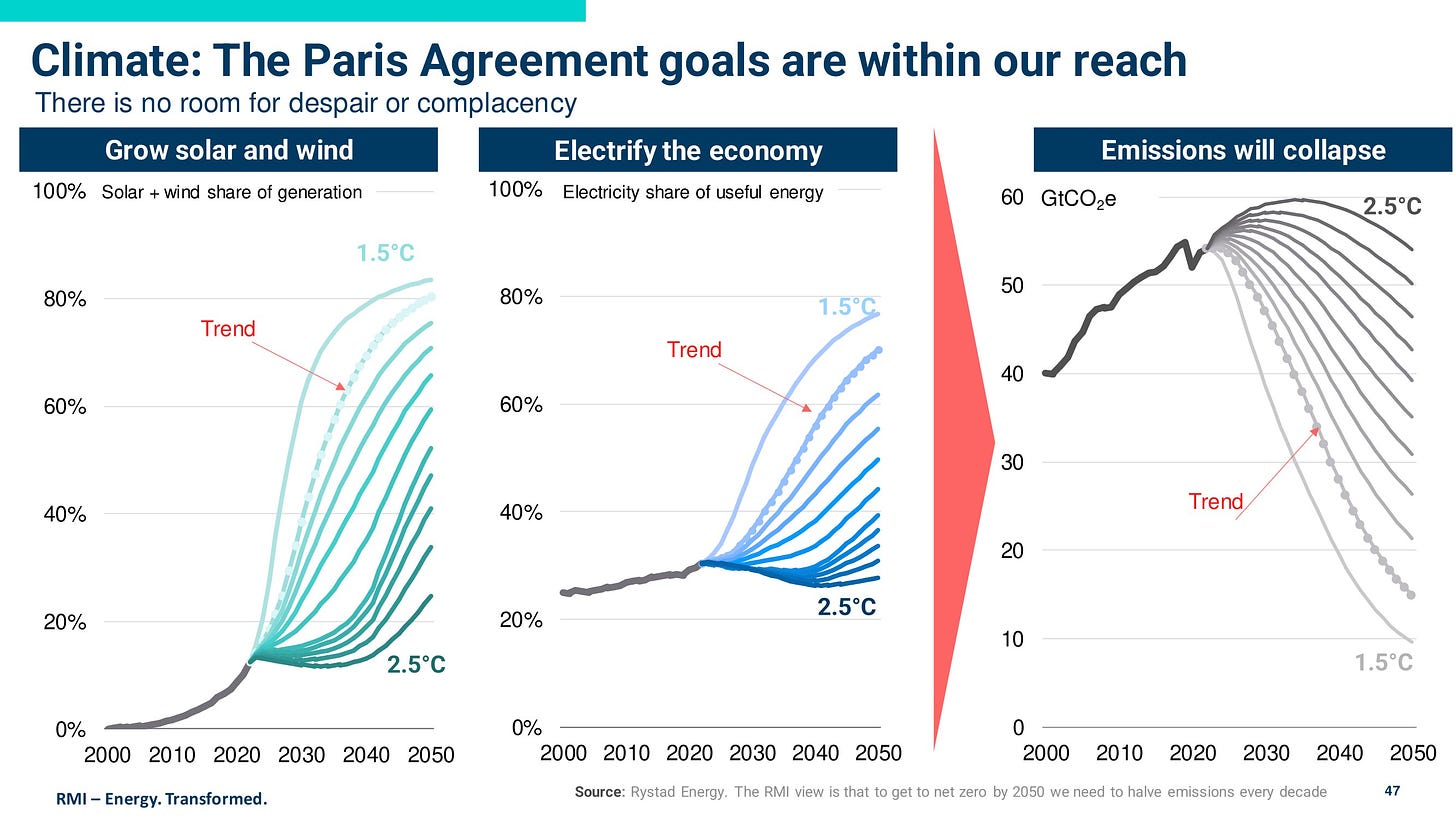

And what I try to tell people is that there no room for either complacency or despair. We’re close to missing the 1.5 Celsius target, but with the renewables buildout, we’re also on track to avoid the RCP 8.5 pathway. The worst of the pathways, to 4 or 5 degrees Celsius, what we would have done if we built coal through 2100. I know that you have spent decades warning people that this is huge and under-appreciated as a massive threat. But I'm seeing in my peer group that a lot of people have totally accepted that it’s a massive threat, and they're not being activists because they think it's hopeless, not because they think it's not a threat. So how would you push back on the doom-ism?

I think I’d say, it’s too early to be a responsible doomist. I’m not saying that there won’t be a point, perhaps, where we’ve more or less lost this battle. But we’re not there yet. We have enormous possibilities, due to the sudden and dramatic fall in the price of renewable energy for making progress at a faster pace than we've made it at any point in the past. We should play out at least this decade and see how much we can get done!

Now, I do think the climate science is scary. I have long thought that though science has gotten the relative rise in temperature just about right, the forecast of how much the temperature is going to go up, we’ve also managed to dramatically underestimate what the impact of each tenth of a degree was going to be. And the impacts we're seeing are very large and scary. The momentum, the impacts on polar ecosystems and things, frightens me. But I think we still have room for enormous amounts of good work to be done. And so I'm gonna keep trying to do it as long as it seems to me a sensible thing to be working on. I don’t really understand the point of despair in that regard.

What are your thoughts on the most promising decarbonization technologies and how citizens and policymakers can act to move them forward? For example, you’ve written about your landmark Heat Pumps for Peace and Freedom proposal, dematerializing shipping, et cetera.

The holy trinity is heat pumps, induction cooking, and e-mobility. E-cars or, as I’ve really begun to think, e-bikes. E-bikes are going to be a remarkably important technology. There are lots of other things that I hope develop over time. I wrote a piece about a year ago saying that I'm very much looking forward to the blimp era.

There have been some interesting international finance deals announced recently where richer countries and private-sector entities pledge to help finance a country’s energy transition if they pledge to meet emissions reduction targets. For example, the recently concluded Just Energy Transition Partnership deals with countries like Indonesia, Vietnam, and South Africa. [At almost the exact moment this question was being asked, a fourth JETP deal, with Senegal, was announced]. What’s your take on this?

There’s a huge amount of excess capital in the Global North and a huge amount of excess need in the Global South. You have to figure out a way to get capital from the north to the south to make that big investment happen. It’s not mostly going to come through direct government intervention, which would be the most straightforward way, but I don’t think there’s the political will in the north to do that. So I think that a lot of what's going on is an effort to figure out how to use global financial institutions to take enough of the risk out of important infrastructure investments that pension funds and whatever can join in and do them. You've got to be able to access that huge pool of capital, and that probably requires de-risking those investments in one way or another.

So, permitting reform. Permitting reform has been a really contentious subject. There’s an argument that we should go for permitting reform even if it means stripping back environmental protection laws like NEPA, because the overwhelming majority of new energy projects being built in the US are renewable.

So even if a permitting reform bill is sort of laden with attempts at giveaways to fossil fuels, if we just get some key stuff in there for renewables like making it easier to build transmission lines, it will disproportionately help renewables, because that's what international capital wants to build right now.

And we clearly do need permission reform, because we see really vital pieces of infrastructure, like the SunZia and TransWest clean energy transmission lines, taking like fifteen to twenty years to get through all the permitting! So what's your take?

I think that if I were in charge of permitting reform, it would come with a climate test like the one that applied to Keystone. If this thing, whatever you want to build, if it makes climate change worse, then you shouldn't build it. I would give real extra weight to frontline and indigenous communities because they've taken it in the neck historically, and they should have more right than anyone to stand up to these things. And I would structure permitting reform so that it's easier to get a permit if you have some community ownership, some skin in the game for renewable energy projects.

Another question: the Willow Project [a proposed oil extraction project in northern Alaska that President Biden controversially did not attempt to stop, likely in an effort to keep swing Senators Murkowski and Manchin aligned with the administration]. Just to start with, it’s a nightmarishly stupid project, they’re planning to use machines to freeze the ground where the permafrost is melting due to climate change, so they can extract more oil to continue climate change. But what concerns me is, I’ve seen people online saying, “Oh, this means Biden’s completely useless on climate change.” And that's just not at all true. The Inflation Reduction Act is economy-transforming, a much bigger move for good than Willow is a move for bad. How do we inject that nuance into the discussion where we say, yes, this is an awful thing, but on climate the Biden Administration is still moving very, very largely in the right direction? And also, this awful thing might not actually happen anyway because we're moving away from oil. It's very possible that by the time the Willow drilling platforms are ready in 2029, there won't even be market demand for that oil.

Part of the problem is that we’ve waited so long that we have very little margin here. Every new oil development is just a terrible idea. And of course it sends a really invidious signal to the rest of the world that it's okay to keep doing this stuff because we're doing it, and it’s not. You can't make the numbers work if we keep building out fossil fuel infrastructure.

I think it was a mistake, and truthfully I think it was a political mistake for Biden to do it. I think he loses more by alienating young people and climate-minded voters than he gains by whatever gains he makes with the Manchins of the world.

We’ll have an election next year, and my view of elections is that they are not morality contests. They’re usually a binary contest between two people and one of them’s going to be at least marginally better than the other one and so that’s the person you end up voting for. We’ll get there. But I don’t think one needs to congratulate Biden on doing this. I mean, 10 years ago the Obama-Biden Administration turned down the Keystone pipeline on the grounds that it was bad for the climate. That strikes me as a straightforward test. And you know, ten years further on, it's that much clearer. just how dangerous our situation is! It's that much warmer, and it's that much cheaper to build the alternatives.

To be clear, I agree that Willow is awful. It should not have been approved, and it should not be built. But what I’m worried about is the effect of that sort of attack on Biden from the climate movement. Given that the US is so precariously balanced between Democrats and Republicans, Biden and Trump essentially, there’s an argument that it’s massively counter productive to attack the Democrats, even when they do bad things, if there’s an election is coming up. Because any attack on them, even if it is a decision we strongly disagree with like Willow, might be pushing sort of young voters and climate voters who don't see the whole picture on other stuff like the Inflation Reduction Act into thinking that Biden is useless if you care about the climate. When, in fact, we really do need a Biden Administration to get like incredible wins like the Inflation Reduction Act.

I think that the wisest policy is just to try and tell the truth on all these things. When politicians do things that are bad, it's worth saying it, and when they do things that are good, it's worth saying it. And I think in general, it’s best never to count on politicians to be your salvation. They’re tools. And if we shift the zeitgeist, then they will shift in our direction. That’s why we keep building movements.

What do you you want to share that I haven’t already asked? What is the key piece of information you want to get out there that we haven’t already covered?

The key remains building movements that can push for change. We’ve got two tasks now, it seems to me.

One is to shut down as much of the fossil fuel industry as we can. And that’s a huge and ongoing and crucial task, because they are strong and deceitful and bad. Existentially dangerous.

And the other task is to figure out how we’re going to build out clean energy, fast. That’s also an organizing challenge, because there’s 140 million homes and apartments in America, and each one of them has three or four machines in them that need to change. And even if people are willing to do it, it's still a huge, organizational and logistical lift to make that happen, and it's going to require good organizing there too.

The American default is always to think of problems in very individual terms, what can I do as an individual in my house. That's important. But the most important thing an individual can do is join together in movements large enough to make dramatic change, both the change of shutting down the fossil fuel industry and the change of building clean, fair, thriving communities across the country.

And I think the other thing that I would say is that we’re at this moment where we could if we wanted to, end the burning of stuff. After 700,000 years of burning things, we don’t really need to anymore. We now can take full advantage of the fact that there is a large ball of burning gas up there in the sky.

“After 700,000 years of burning things, we don’t really need to anymore. We now can take full advantage of the fact that there is a large ball of burning gas up there in the sky.”

-Bill McKibben

And the biggest reason to do it is obviously the existential risk posed by climate change. That's the biggest thing humans have ever done. But there are two other reasons to do it.

One, burning stuff is just bad. Nine million people die a year, about one death in five on this planet, from breathing the combustion by-products of fossil fuel, mainly those particulates. But they don't need to anymore. And, you know, a lot of that's in urban Asia. But a lot of it's here, too. There's hundreds of thousands of cases a year of childhood asthma in America, and we all know who gets it because they're the ones who get to live next to the highway and the refinery, and whatever else.

And the other reason is, it sucks to live on a world where you depend on a few resources that are just available in a few places, because the people who control those places end up with way too much power. So the Koch brothers, who are our biggest oil and gas barons, can take their winnings and wreck our democracy. Vladimir Putin can take his winnings and launch a land war in Europe.

It'd be very nice to live in a world where we depended on the sun and the wind, because they are everywhere.

“It sucks to live on a world where you depend on a few resources that are just available in a few places, because the people who control those places end up with way too much power…Vladimir Putin can take his winnings and launch a land war in Europe. It'd be very nice to live in a world where we depended on the sun and the wind, because they are everywhere.”

-Bill McKibben

That’s a really powerful statement. I really like your quote “After 700,000 years of burning things, we don’t really need to anymore.” That’s huge, that’s really fundamental.

Yeah, I really do think that's the most exciting thing about our moment.

Humans have sort of been defined by combustion. Darwin said that control of fire and language were the two things that set humans apart.

It was good for us for quite a while. You know, we were able to cook food, which gave us the big brain. We could move north and south from the equator. And the anthropologists think that standing around the campfire for millennia developed the social bonds that mark our species. When we learned to control the combustion of coal and gas and oil in the Industrial Revolution, it produced modernity.

But now it’s causing us extraordinary trouble. Geopolitical trouble, public health trouble, and above all, that unbelievable climate damage. So it’s good news that we happen to be at the moment where we can substitute the fire from the sun for the fire on our planet, and do it easily and cheaply. That’s the great transition of our time, if we can.

Another great interview. McKibben is one of my heroes. Someone whose prescient wisdom has been born out time and again. Thanks for this!

The CHANGE in McKibben's focus is welcome because the former focus, to just say "no" to fossil fuel development and transportation projects in one rather important country, the US, reduces global net CO2 emissions very little and at a correspondingly high cost per unit of net CO2 emission avoided. And beyond the economic cost there is the political opportunity costs on not having advocated tor lower cost, more effective ways to reduce net CO2 emissions.

And the change to saying "yes" to investments that permit reductions in net CO2 emissions, although welcome and indeed necessary, is not enough to promote those investments. Nor has he abandoned the high-cost no saying.