The Weekly Anthropocene, August 3 2022

Dispatches from the Wild, Weird World of Humanity and its Biosphere

The Pacific Ocean

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) is a vast swathe of Pacific seabed named after the relatively nearby Clipperton Island, a tiny, uninhabited French possession off the Pacific coast of Mexico. Now, a new study chronicles the discoveries of a team from the UK Natural History Museum that used an undersea drone to collect faunal samples from the CCZ’s seamounts and abyssal plains. They found 55 specimens from 48 different species-and, amazingly, only nine of those were species known to science, meaning they discovered a whopping 39 new life-forms! (Pictured above: Psychropotes verrucicaudatus, a previously known purple species of sea cucumber)

I’m using generic words like “life-forms” here because the researchers’ haul was incredibly diverse, spanning five different phyla: Annelida (segmented worms), Arthropoda (insects, arachnids, most of what we think of as “bugs”), Cnidaria (corals, jellyfish, and company), Echinodermata (starfishes, sea cucumbers, and their relatives), and Porifera (sea sponges). For context, all animals with backbones, from lampreys to lions, are part of just one, the phylum Chordata. (Pictured above: a polyp from a newly discovered species of soft coral in the genus Chrysogorgia).

(Pictured above: a newly discovered red sea cucumber in the genus Psychronaetes). These multitudinous discoveries underscore how much we still have to learn about deep-sea megafauna. Fascinating news!

United States

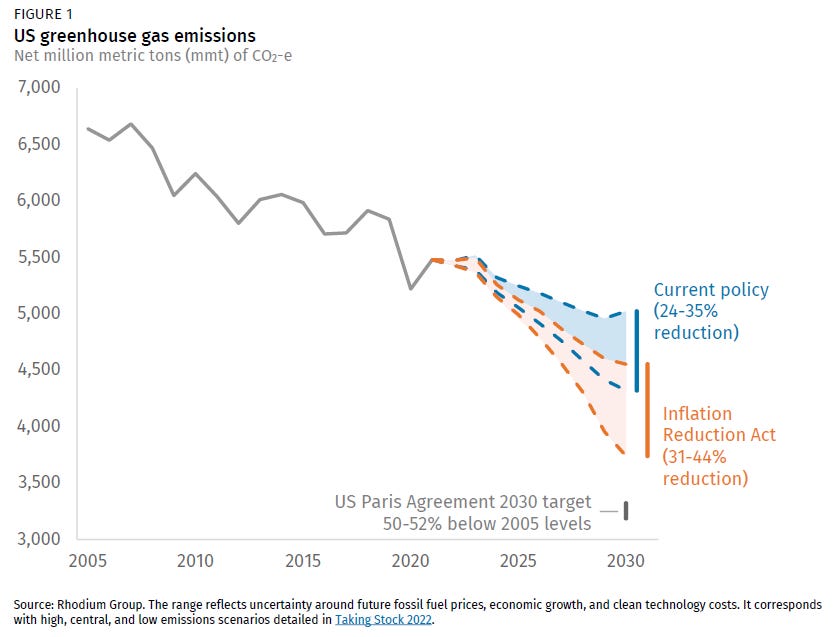

Maybe, maybe, maybe: by far the biggest climate/environmental news out of the US this week is that pivotal Senator Joe Manchin finally agreed to the text of a new reconciliation bill. The proposed Inflation Reduction Act would include a historic, potentially transformative investment of $369 billion in energy and climate spending. If passed, this would be by far the biggest federal climate action in US history, a massive win for the Biden Administration, and could reduce American emissions 37-41% from 2003 levels by 2030 all by itself! This comes just a week after Manchin appeared to rule out any new climate funding, and has left climate-conscious observers with both whiplash and breathless hope. (Pictured above: a preliminary assessment of the emissions reductions the Inflation Reduction Act would likely bring, from the Rhodium Group. Note how US greenhouse gas emissions are already falling due to coal retirement and renewables deployment; this would accelerate these trends closer to where we need to be).

However, there have been far too many close calls and deals that fell through over the last year to celebrate before the bill passes Congress and is signed into law. We’ll report on the act’s provisions in detail if and only if this happy outcome eventuates!

While the climate scene waits with bated breath to see what happens in the Senate, already-passed bills, executive orders, state governments, and private entities continue to advance the renewables revolution.

A coalition of 17 US states, Washington DC, and Quebec have signed on to the Multi-State Medium- and Heavy-Duty Zero-Emission Vehicle Action Plan, a jointly created action plan targeting 100% electric medium and heavy-duty vehicle sales (i.e. vans, pick-up trucks, large trucks and buses) by 2035. This plan is not legally binding, but it does illustrate a shared commitment to a policy agenda that can now be enacted through regulations and legislation. For example, California, Washington, and Oregon, all among the 17 states on board with this, have already adopted shared Advanced Clean Trucks regulations mandating that manufacturers sell increasing percentages of zero-emission vehicles in their states. New York has also passed legislation mandating that all new cars and light trucks sold in the state be zero-emission by 2035, and all medium and heavy vehicles by 2045. Great news!

The Senate and House have passed the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act, a $280 billion investment in American industrial capacity. (Interestingly, this may have only gotten Republican support in the Senate due to Manchin’s earlier and now-superseded ruling out of a climate deal, in a rather clever piece of political maneuvering from the Democrats). And President Biden said he’s excited to sign it into law shortly, making final enactment into law a sure thing. While it’s not primarily a renewables-focused bill, there are several important side benefits. In addition to $52 billion in direct subsidies for semiconductor manufacturing in America (already a help for climate action, as semiconductors are a key EV component), the bill invests over $11 billion in Department of Energy R&D into clean energy and carbon removal tech, $11 billion in regional technology hubs, and expands some climate-related NSF and NASA programs. As weird as it seems to write, great work Congress!

“The CHIPS and Science Act is another big step in our fight to lower energy costs and reduce America’s dependence on expensive fossil fuels,” said Chair Kathy Castor (D-FL) of the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. “By empowering America's industries to produce the semiconductor chips that are essential to our clean energy transition, we will ensure the United States remains competitive in the global market, limiting our dependence on countries like China and addressing supply chain issues for critical technologies. Importantly, we will also modernize our approach to challenges posed by the climate emergency, including risks to our economy, national security, and energy independence.”

“The CHIPS and Science Act invests in the best of American innovation and the strong spirit of the U.S. workforce. Through critical new funding, we will advance research to expand clean energy, modernize our grid, develop carbon removal and clean industrial technologies, and reach new frontiers in the fields of climate science, clean water systems, and critical minerals. This legislation will also benefit environmental justice communities, with investments to build regional technology hubs, expand grants to economically-distressed local communities and labor markets, and diversify our thriving STEM workforce.”

The six new climate-related executive orders President Biden announced on July 27 were (understandably) little noticed amidst the big news of the CHIPS Act and the potential Inflation Reduction Act. However, they’re still moving things in the right direction, including further expanding wind power leasing in the Gulf of Mexico, creating a new program to help connect low-income households with electric bill-reducing community solar projects, allocating more of last year’s infrastructure bill money to help communities prepare for floods, droughts, wildfires, and extreme heat, and establishing heat.gov, a one-stop shop for extreme heat information and advisories.

And in the last week of July, the largest utility solar plant in Connecticut (pictured above) was completed, after an unusually fast seven-month installation time. Located in Canterbury, CT, these 150,000 solar modules will now be feeding 66.5 megawatts of alternating current (MWac) into the New England grid. This isn’t at all an unusual occurrence these days, just one more of many clean, low-emissions renewable energy plants keeping the lights on.

Nepal

A new census announced on July 29 has found that Nepal is leading the world in tiger conservation, nearly tripling its tiger population in the last twelve years. In 2010, Nepal had 121 tigers, and with other tiger range countries pledged to attempt to double that by 2022. Now, the Himalayan nation is home to 355 wild tigers! That’s a number so high that some scientists think it’s nearing the maximum “carrying capacity” the country’s wild places can support. This comes on the heels of an International Union for the Conservation of Nature report estimating that there are now between 3,726 and 5,578 wild tigers total-a 40% increase from the 2015 estimate, but still far below the estimated 100,000 in 1900.

With Nepal’s new high tiger densities come new challenges: tiger attacks on humans and wildlife have increased in the past few years, especially around Chitwan National Park, part of a forest complex home to a subpopulation of 169 tigers. (Pictured above: a tiger in Chitwan). The high population densities have driven some weaker tigers out of the core protected area and towards human settlements, leading to tragedy: 16 people have died due to tiger encounters in 2021-22 in Nepal after just 10 tiger-caused human deaths in Nepal in the previous five-year period. This is already driving new efforts to “tiger-proof” local communities: local tiger protection teams are building more secure livestock stables and teaching local children about tiger behavior and safety in communities near national parks. Park authorities are creating more waterholes and grassland landscapes amidst the forest to encourage higher deer populations, to ensure the availability of non-livestock tiger prey. And the government has taken seven particularly dangerous tigers into captivity.

One constant that this writer has noticed in years of writing about endangered species and wildlife revivals is that the moment a species recovers to the point that it’s no longer on death’s door, a first-level victory against extinction, conflict with humans will start to ramp up again, possibly exacerbated by the lack of cultural memory or generational experience in how to deal with a species that’s been absent or scarce for a while. We’ve seen this pattern before in the US with once-rare white-tailed deer now commonly involved in car collisions, resurgent sperm whales “stealing” cod from commercial fishers off Alaska, and more. With big, dangerous animals like tigers, of course, it’s vitally important to keep working for the next level of successful conservation: finding a safe equilibrium that works for both the survival of wildlife and the safety and comfort of humans. The case of Nepal, both the original boom in tigers numbers and the efforts to find a safer way for humans to live alongside tigers after attacks, exemplifies the delicate balance of forging a thriving, coexistent Anthropocene.