Repost: Interview with Sy Montgomery, Wildlife Writer Extraordinaire

A conversation on animals, humans, and how they can coexist, now republished

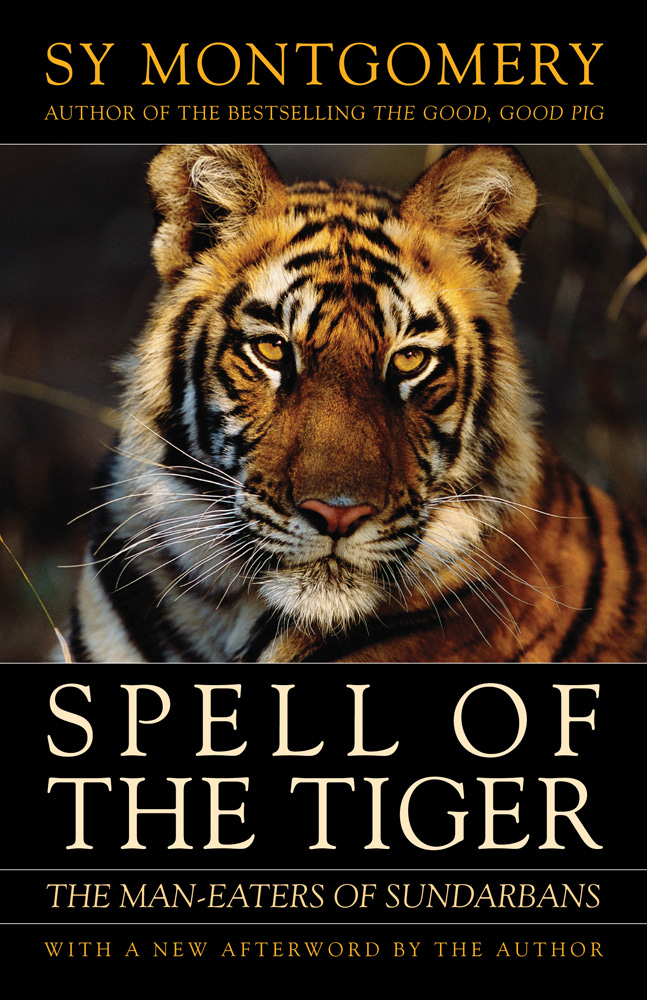

Sy Montgomery is one of The Weekly Anthropocene’s personal heroes (and longtime favorite authors): a brilliant science and nature writer who has traveled the world to tell the stories of wild creatures and the scientists working to protect them. She has written over 30 books for children and adults, including Spell of the Tiger, a chronicle of the wetland tigers of the Sundarbans, The Soul of an Octopus, in-depth encounters with the octopuses of the New England Aquarium, Search for the Golden Moon Bear, a quest across Southeast Asia in search of a possible new species, Journey of the Pink Dolphins, a voyage through Amazonia to learn more about the mysterious boto river dolphins, and many more.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Ms. Montgomery’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

This interview was first published in May 2023, and is now republished for a wider audience.

How did you get to where you are now? How did your story start?

It’s a good question. Many young people today feel, like, I go to college and my major will be an escalator directly to the job I’m going to get. While your experience in college is certainly important and helpful, there was no way to major in jungle exploration and writing books about it! And sometimes, right out of school, you don’t get to do the exact thing you want to spend your life on. I knew that. When I got out of school, I triple majored in journalism, French, and psychology, and I took a lot of biology as well. I felt that I could help animals the most, with what talents I had, by writing about them and connecting people with animals, because I felt the disconnect was why we were crowding and polluting and murdering so many species of creature. I was shocked to learn that just the things that my family bought in a routine day could be choking a whale or killing an unborn eagle in the egg. And once people knew, I felt, the ways that we could preserve animals, that would change things, if only I could reconnect them.

So I wanted some experience writing on deadline, with editors, and with readers who are going to give me feedback. I got a job out of school working for a daily newspaper with five editions, and after working for one year covering basically everything that went on in nine rural towns, I worked my way up to the job that I wanted at that time, which was a science/environment/medical writer. That was great! I was purposefully working in New Jersey, because it had more scientists and engineers per capita than any other state. I was purposefully working at a medium-sized newspaper, not a tiny newspaper, because I wanted to reach a decent amount of readers, but if you’ve just graduated your chances of getting a really good beat on the New York Times are small.

I got my big break when I joined, as a volunteer, an Earthwatch expedition to South Australia. It was there that I really experienced what it was like to study wild animals in the field. Pamela Parker, the principal investigator, saw that I was on fire to do this, and would’ve loved to have hired me as an assistant or at least given me a ticket so I could go back. She didn’t have any funding for that. But she did have a regular camp much of the year at Brookfield Conservation Park, and she said that if I came and studied whatever I wanted, she would give me food. So I quit my job and moved to the outback.

And everyone said I was crazy! I had this very good job, I was well paid, I was winning awards, I was appreciated, I was with people that I cared about. I wasn’t, you know, wasting my time in any way. But I set that aside, and all the perks of having salary and health insurance, to walk off the cliff of following my dream.

After six months living in the outback in a tent, I knew that as much as I had loved working at the Courier News, I needed to work for myself now, and I needed to do exactly what I’m doing now. The thing is, you know, sometimes the money isn’t there but you find it. Sometimes the opportunity is not there in front of you but you make it. And that is what I did. And if I did it, everyone else can do it too. I am not that special! I have some talent, and I certainly work hard, but I’m not any smarter than you are, or more talented than you are. You can make this work!

One of the things people don’t think about when they’re deciding what they’re going to do for their future is…one of my great assets is, I don’t need a whole lot of stuff. I don’t need a nice dress, or a nice car, or a big entertainment budget. Not needing a lot of stuff gives you a ton of flexibility, particularly when you’re young. And not having a family I had to support or look after, that was tremendous, that meant I could funnel everything into my work. And that doesn’t mean that if you do want nice clothes or a nice car or a spouse and children, you can’t do what I do, but it gave me a lot of freedom. And I married a man who feels exactly as I do, that the writing and the work is the greatest joy, and comes first.

Thank you. That’s really inspiring, honestly!

I love your book Spell of the Tiger, and I was recently interviewing Bangladeshi climate negotiator Quamrul Chowdhury when we discussed the importance of the Sunderbans. There’s more saltwater intrusion now, there’s been a couple cyclones, notably Cyclone Amphan was really bad. It’s an area that’s at the front line of climate change, but also a very resilient area, because they’ve been living in a wetland for a long time, and as you know much better than I do they’ve developed a rich culture around that. I'd love to hear more about your Sunderbans experience, and your thoughts on the future of this amazing human/tiger landscape in the 2020s as climate change intensifies.

My experience going there was crazy, as you know from the book. I show up, and after I left Bangladesh and went to India where most of my work was going to be, I discovered that my translator, who also had the speedboat, was not going to be with me. But sometimes the universe throws you a curveball and it’s really a bouquet of roses. And this is why I think my book was able to tell the truth of these peoples’ understanding of the way the world stays whole thanks to predators. I think this is why this is the largest intact mangrove swamp on Earth, because it has five hundred tigers guarding it and it was inhabited by humans who understood the sacred relationship between predators and the health of our environment. Even the people who had lost family members to tigers, they were like “Gee, shouldn’t have gone in to cut trees in that area.” No one blamed the tiger. No one. Everyone understood that there was a tiger goddess, a forest goddess, and we had to respect them.

The thing about mangrove swamps is, as resilient as they are, in the past they were able to move. If your mangrove swamp got wiped out in these hundred kilometers, there was another hundred kilometers upstream where a new forest could rise. Right now, India and Bangladesh are two of the most crowded countries of the world. The mangrove forest doesn’t have anywhere to move. Thank goodness it is preserved, but it used to be a landscape that shifted and had space to shift, before they came up against a big tide of humanity. And climate change is a very big deal. As resilient as mangrove swamps are, I just pray that they can hang on through climate change. When an area becomes way more salty than it used to be, that’s not good for any of the creatures there. It’s not good for the people, not good for the animals, not good for the plants. We are changing the rules way faster than they’ve ever been changed, at least in the past 66 million years. The asteroid impact was pretty instant change, but we’re a close second.

That’s a powerful perspective.

You've been in the field all over the world and seen and done some extraordinary things, from living among wild emus in Australia to witnessing gigantic snake mating balls in Manitoba. What are some of the most extraordinary, awe-inspiring, arduous, or just plain weird experiences you've had?

One was two weeks ago! I just got back from the Dominican Republic. And there I went on a boat with eighteen other guests, 70 miles from any shore, out in the Atlantic, and swam with humpback whales.

Wow!

Yes! It was an epic journey, too. It’s not always this choppy in the sea, but it was very, very choppy, a tough crossing. We lost an entire day to eight and nine foot waves that we simply couldn’t cross. We got to the place we’re going, Silver Bank, right over a coral reef. It’s not as deep, and the whales take sanctuary there. We would go out in these two little skiffs every day, and there would be spotters. Not because it was hard to see the whales, but because you don’t want to go in the water with a whale who’s breaching. Or with an infant whale who’s having a tantrum-because he’s as big as a school bus! You don’t want to interrupt them or disturb them when they’re doing something important.

So we waited until the whales were just hanging out in the water, and then the spotter would get in the water and say, come on in. And quietly, we would slip through the water, and swim a bit of a distance, and then just float at the surface on snorkel. Our faces were in the water, and beneath us we could see 40-ton leviathans swimming in a luminous liquid environment, the beating heart of the planet. They move at a different pace than we do. The quality of your vision is different underwater, it’s blue and cloudy. It’s almost like a dream. It’s really almost more like waking from a dream, because we live our lives on tiny portion of the Earth that is covered with land, we aren’t in the largest habitable space on our planet. They are. To be there with them, and to watch a 40-ton whale turn and glide benevolently toward you, and look you in the eye, and slide past you thirty feet away…it’s just a magic experience.

And for me, this was the first time in 16 years that I’ve gone anywhere for more than two days when I didn’t have an assignment, a job, a deadline. I did this for my soul. I’ll eventually write about it, but I couldn’t have another deadline hanging over me. I committed to do this back in the summer, before these two huge projects came in, and I was really working under the gun. As this whales trip approached, I started thinking, oh my god, I’m not going to have time to do this. But I did make time, and I did do it, and I’m so, so grateful.

Wow. I’m just blown away by that. There’s really a sacred quality to what you’re saying.

You would feel it too. Even during whale watches, just seeing these leviathan creatures soaring out of the water, that’s transformative. But there was something extra special to being in their environment, part of their environment, literally being embraced by the water.

The most amazing thing that we saw… We saw a mother and her month-and-a-half old baby being escorted by a male who wanted to mate with her. As the male came closer to us, we cold see that part of his flipper, his arm essentially, had been truncated by something, and he had this immense scar on his back. That scar could have been made by nothing but entanglement in fishing gear. He could never have escaped from entanglement that severe without a trained team of humans helping him. And when he saw us, he was very chill. I feel certain it's because he saw, humans had helped him before, here are some more humans, I’m not going to be frightened. I’m not going to try to get away. I’m not going to be aggressive and try to protect my female and this calf, they are safe. He welcomed us.

Wow. That is extraordinary. You have a palpable deep sense of empathy for other living creatures, and I think the world needs more of this. I mentioned in a previous book recommendations post on my Substack that your writing was fundamentally about animals in a very unusual way, going beyond human constructs around animals to really engage with what life is like for that species. I'd love it if you could share some of your experiences with the creatures you’ve made friends with, trying to establish a connection across species divides.

I’m going to make you the first person I share this with. I’ve got a new book coming out in September, which is called Of Time and Turtles, Mending the World Shell by Shattered Shell. And for the past three years, I’ve been working with a turtle rescue. They rescue the turtles that we have in our streams and ponds [in New England]. They rescue Blanding’s turtles and spotted turtles and snapping turtles who’ve been hit by cars, they rescue box turtles and painted turtles who’ve been chewed by dogs, and turtles who have been run over by lawn mowers. And turtles also of exotic species who have been abandoned by their owners, often just left in a cardboard box in the middle of a city on a November day in New England. We also did a sea turtle rescue with them one day. I’ve worked with several other places including a nest protection outfit, and raised baby turtles up myself for release.

When I started that project, I had no idea the pandemic would be coming, but it turned out to be a great thing to do during the pandemic, because our whole world seemed to break apart. Even the quality of time seemed to be ruined. And one thing about turtles is, they understand time. These are ancient species that arose with the dinosaurs, they are very long-lived, they move at a different pace than we do. They are wonderful teachers. I’m now 65, I’m entering that age class of elders, and they are a great guide to me as I enter that age class.

When I first went to the turtle rescue, I wondered, which of these turtles, these 250 to 1,000 turtles that are at that turtle rescue at any one time, will I get to know as individuals? Who is going to show themselves as a major character in this book? Who is going to emerge as a personality with a powerful story to tell? I trusted that they would reveal themselves, and they did.

One of the main characters in the book is a 42-pound adult male snapping turtle, about my age, named Fire Chief. And the first time I met him, he was just so huge. He had been hit by a car, his back legs had been paralyzed, and he was in a hospital pen. Not a dry pen, a giant aquarium stock tank. It was small compared to a pond, but big compared to where you would put any turtle in your own house. Natasha and Alexia, who live in the house, the turtle rescue’s in their basement, they fed him a banana. And I saw this head that I thought was the size of my thigh erupt from the water like a crocodile, seize this thing, and murder the banana. And I thought, oh my gosh, what a scary turtle! How can they take care of this guy? Well, just a few months later, the artist working with me on the book, Matt Patterson, and I, started doing physical therapy with Fire Chief. And we got so we could pick him up, we could pet his head. He would let us feed him by hand, not dropping in a banana at a distance, but holding out a banana in your fingers and holding on to the banana while he bites it.

And he got his legs back! He now can move his back legs, he can walk, he can use his tail, which you need if you flip over. His story is woven throughout the book. But I can tell you, on the QT, that the end of the book is so triumphant. We dreamed of the day we could release him. We went to his old pond where he was hit, and we were devastated when we saw it’s right on the edge of a highway! So we couldn’t release him there. When he crawled there as an infant it was a little country road, but now it’s a freakin’ highway. He crosses from summer pond to his winter pond every fall and every spring. He would be a sitting duck. You just can’t move fast enough on that kind of a highway to get across, particularly if you’re still somewhat slowed due to a huge spinal cord injury. So what do to?

Well, what we did was, Matt and his wife bought a house on the same street as me, moved there, dug a pond, and that’s where he lives today!

Wow! That is extraordinary!

I can see him every day!

That’s so great!

Animals reveal themselves to you. They show you their personalities. And sometimes you’ve just got to throw yourself of a cliff and know that these animals will show you who they are. I just have to trust the universe that there’ll be some drama that’ll make my story work.

And the same was true for The Soul of an Octopus. I did not know when I lifted the lid of that tank that Athena would be interested in letting me touch her. Because she hadn’t let any other visitor touch her head. But she let me touch her head. She was ready. I didn’t know that the aquarium would let me come in every week and canoodle with their octopuses. I didn’t know all the dramas that were ahead. I didn’t know that Octavia would end up laying her eggs. I didn’t know that we would have the horrible scene where Kali crawled out of her tank and died, I could have done without that. You don’t know what the universe has in store, you’ve got to trust the animals, even when you can’t trust yourself.

Thank you for sharing this!

I saw online that you're currently fostering baby Blanding's turtles! That is SO COOL, can you tell me more about that? Can anyone do this?

You need a permit from the state. I have volunteered at a nest protection site near us where five species of turtles nest: Blanding’s, spotted, and wood turtles, as well as the commoner snapping turtles and painted turtles. This year, I’ve got four darling little Blanding’s. Some schools also do this, it’s called head-starting. I would urge readers to look up Zoo New England and see if they can get involved in the fostering problem. Children are doing this in classrooms, but with a state permit and with state oversight, since these are endangered animals.

Turtles face unique threats today, from roads to a horrible, illegal trade in turtles, which feeds a market centered in Asia, but they’re coming over here to take our turtles now. And of course development, climate change, the things threatening everybody. But turtles are uniquely threatened, because they are so slow and because of their nesting habits. First of all, most eggs don’t even hatch! Everything eats turtle eggs. Skunks dig them up. Dogs dig them up. Foxes dig them up. Ants can kill them. Trees can kill them! Trees can send their roots into the egg to suck their moisture, and kill the eggs in that way. When the babies hatch, everybody its them, they’re little tiny things. Frogs will eat them, fish will eat them, crows will eat them, everything eats them.

So, considering that we’ve put turtles in such a bad position, Zoo New England and a number of other places have thought, you know what, let’s give them a little leg up. Let’s take these babies from the moment they hatch and let them grow up until they’re just a little bigger. Let’s keep them through the winter and let them grow. So that now they’re too big for frogs to eat. Too big for many fish to eat. More difficult for birds to eat. It just gives them a little leg up.

So I’ve had these four turtles, and since they’re Blanding’s, in honor of Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House I’ve named them Myrna Loy, Cary Grant, Melvin Douglas, and William Steig. I’m going to be letting them go when the water gets warm enough, probably in June. And last year, I started with painted turtles, and I had the most amazing experience. One of my painted turtles drowned. And they drown sometimes in the wild, we just don’t know it. He got, freakishly, under a suction cup that held their basking platform to the side of the tank. His name was Monet, and I picked him up, and I did CPR on that turtle for 45 minutes. He came back to life! And I released him in the spring with everybody else.

That is amazing!

It was very hard letting him go last year, but he and three of the other four, when I let them go in the river that their mothers had crawled out of the year before, a beautiful river, they swam out a little ways, and pulled their heads out and looked at me. Seeing that turtle come back and say goodbye, it doesn’t usually happen, but it is known to happen in some cases. We’ve let plenty of hatchling turtles free, and we’ve released a lot of healed turtles. For turtle rescuing, the goal is to be able to release turtles back into the wild. They have seen that happen before, the turtle swims off a little ways, turns around, pulls its head out of the water, and looks at you on the bank.

I'd love to discuss a fascinating through-line of many of your works. On my Substack, I’m trying to chronicle stories of the duty of humanity to go beyond traditional non-interventionist conservation ethics and actively help wild animals survive, as you've just told me a story about with these turtles.

There are so many stories about people going the extra mile to help animals survive. Some Australian towns are putting out drinking fountains for koalas, to help them survive during heat waves when there’s not enough moisture in the eucalyptus leaves. There’s an emerging idea of urban conservation islands, because a lot of people in urban areas are willing to help animals out, a lot of species like yellow-crested cockatoos in Hong Kong or peregrine falcons in Manhattan are able to survive in an urban area better than they could in a more rural area. I just recently wrote about a group that saved over 1,500 bats from the freak freeze in Texas.

I'm deeply interested in the potential to develop a new ethic to help other species, beyond just leaving them alone, which is historically the highest we’ve aimed for. There’s a semi-apocryphal quote from Saint Francis of Assisi, something like “Not to hurt our humble brethren [animals] is not enough, we have a higher duty, to be of service to them whenever they require it.”

I think there’s a possibility-and this has really influenced my thinking, and it’s inspired in large part by your work-to flip the standard human narrative on its head, and think of ourselves as an older brother, or older sister, or mentor figure to a lot of other species. The least we can do is try to help them survive the convulsions and upheavals of the Anthropocene. So I’d love to hear your thoughts on that.

First of all, hats off to you Sam, for doing this. It is such a balm to people to know that they can help. It’s great when we can write a check, or reduce reuse recycle, but it is such a joy when you actually have a hand in mending the world. And there are so many volunteer opportunities for us to do this. For turtles, one of the things we can do is protect their nests. If you see a turtle nesting, you can rush out there after she’s laid her eggs and literally protect that nest from being destroyed. You can build a nest protector with common materials. Then you have to watch, because when the baby turtles do erupt, you want to make sure that they get to their wetland safely and aren’t stuck in your nest protector. Even feeding birds, anything we can do in the way of pollinator gardens for hummingbirds and bees. There are so many opportunities, and they don’t require you to give up your job or travel halfway around the world or spend a lot of money or take a training course that’s going to last half a year.

And there are also opportunities if you do want to fly halfway around the world, if you do want to join a team of people protecting animals. There’s tons of places that need volunteers on turtle nesting beaches. Earthwatch has projects assisting scientists in finding better ways to protect everything from elephants to sharks to worms. There’s so many exciting opportunities. In a world in which we often feel helpless and hopeless, offering these just empowers us. And these things are fun! It doesn’t have to be something that feels like you’re depriving yourself, or it’s a chore. It’s the opposite of that.

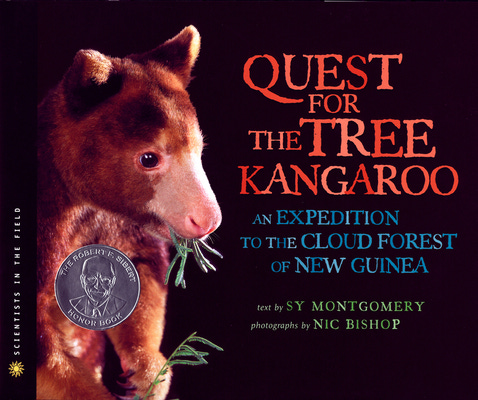

You've written many incredibly engaging pen-portraits of scientists in the field, from Lisa Dabek to Gary Galbreath and Sun Hean. I'd love to hear about what you’ve learned writing about science and scientists, and the importance of the efforts you’ve led to share such people as role models to kids in our society.

You are so right, that was my intent, to show people that no matter what your talent, your disability, your interest, your grades, you can help animals. You can totally be a scientist!

Lisa Dabek had horrible asthma. She couldn't even have a dog or cat when she was growing up. And now she's working ten thousand feet up in the cloud forest studying tree kangaroos. At first, she really wanted to study animals, so she did her own study on the asphalt roof of her house watching ants. She later studied humpback whales. There is a workaround, you can find it.

Sam Marshall, the Tarantula Scientist, was the world’s top expert on tarantulas when I wrote about him. And he was told, you suck at school, you’ve got terrible grades. He didn't like science. He thought he’d be a failure. But then he discovered, guess what, I really love animals, and I really love spiders, and I can make this my career!

Gary Galbreath was the opposite, he always wanted to be a scientist. For some of us, it’s given to us to know what we want to do. But Gary had obstacles to overcome as well. He got a huge grant, and wrote this enormous proposal to study colobus monkeys in Africa for his Ph.D. He was practically packing to get on the plane, when the grant was cancelled! He couldn't study the colobus monkeys. Instead he ended up studying nine-banded armadillos. And he became, at that point, the world’s expert on the nine-banded!

E.O. Wilson, who I knew well, and who was always the kindest gentleman, he thought he would study birds. But he got a fish hook in his eye when he was a child, and so he couldn’t see distant objects. But he could see close up. And so, he studied ants. And the ants gave him everything.

And so that's what I would learn from scientists. No matter what obstacles you face, or what talents you have, you can bring them to bear on what I consider the most important thing we can do with our lives: saving the natural world at this turning point in human history.

Wow. This is a really inspiring interview!

Your enthusiasm matches mine! This interview is great because I’m talking to you.

Thank you! It’s a virtuous cycle. I want to make sure to ask the question I always ask: What is the question I haven’t asked that I should have asked?

I always ask that question too, when I interview people. You’re a fantastic interviewer, you’ve asked the most important questions already.

I'm happy you reposted this. Sy is a true role model and as good a writer as she is an example of a well lived life. I have two of her books and they were very good reads.