Encore: Interview with Dr. Vidya Athreya, Urban Leopard Scientist

Leopards in suburban Mumbai, the shrines of Waghoba, human/wildlife coexistence worldwide, and more!

Dr. Vidya Athreya is the Head of Science and Conservation at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS)-India. She is a global expert on leopards in human-dominated landscapes, with years of field experience in the Indian state of Maharashtra. Her research website is at Project Waghoba.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Dr. Athreya’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

Could you share your personal story and your experience conducting camera trap and radio collar studies of leopards in human-dominated landscapes?

We started in 2004. There were a lot of leopards being trapped in the croplands. I myself didn’t believe [at the start] that there would be leopards living in human-dominated cropland landscapes. With the Forest Department, we started putting microchips into the leopards-it was a small budget project-and the Forest Department wanted us to try this because we were telling them that translocation actually worsens the problem.

If you remove a leopard from its territory, which may be a cropland, and put them in a forest where we as humans think that these animals need to be, we found-our work showed-that there is actually a correlation between releases of [cropland] leopards [in forests] and attacks on humans near the release sites. This [translocation] might work well in countries like Namibia where there’s 2 people per square kilometer, but not in India, where you have an average density of 400 people per square kilometers.

You’ve captured an animal not in a forest, but in a cropland, where it’s been born and raised and never seen a forest in its life. And when you take such a strongly territorial animal and release it in a forest, it has no idea about it. It only knows about houses and domestic animals. We surmise that they’ll probably go to the closest houses, looking for food, dogs and goats and stuff. And in a new place that the animal doesn’t know, that can really lead to problems. There are children, there are people all over the place.

So that’s what we found. We started putting these microchips into leopards that were caught in the croplands and that were being translocated elsewhere. At that point, I realized the majority of leopards were trapped only because they were seen and not because they had done anything to people.

That really made we go, wow, okay, that means mothers with cubs, animals that are ten years old, couples, all of these animals are living their lives in croplands without doing much to people. That was fascinating to me. I said, let’s start studying it. I started camera trapping and getting their scat in these landscapes to understand what they’re eating, talking to farmers to see what kind of losses they have due to leopards. And then we put some GPS collars on a few leopards that lived in human-dominated landscapes.

This is fascinating stuff. And, I believe, in addition to croplands, you and other researchers found leopards in Mumbai itself, right, where they were ranging from Sanjay Gandhi National Park into local neighborhoods. That’s even more integrated with humans.

Yes-I think in a lot of cities, the city has grown around the park, or it’s adjoining. The urban national parks that I know of, one is in Rio de Janeiro, one is in Nairobi, then there is one in Mumbai. There are these older national parks which have dense urban settlements surrounding them. The city has come to the park, the city is enveloping the park. And the leopards are still there. There used to be tigers there, but not any more. The leopards are so adaptable, they’ve hung on. And not just hung on, I think they’re doing well, because there’s so many dogs and pigs and bandicoots. There’s a lot of garbage. Next to the park there’s a milk colony, owned by the animal husbandry department, with a lot of livestock used for milk. And when the livestock die, they’re disposed of nearby, and that’s another food source for the leopards.

Mumbai is amazing. Mumbai has leopards, flamingos, jackals, marine life. It’s incredible, the biodiversity. If you’ve never been to Mumbai in your lifetime, you should come to Mumbai, it’s such an amazing experience.

If you google “wildlife in urban spaces,” anywhere in the world, human-use areas are great for carnivores.

I write a lot about that!

Especially obligate carnivores. In India, large cats. In the US, bears, coyotes. Why are they there in some places and not in others? If you ask me, I believe it’s how humans deal with them socially. In cultures where it’s okay to have wild animals around you, and the law does not allow for killing all the time, you will get these animals. In other cultures, where a puma’s in your backyard has eaten your cat and legally you’re allowed to kill it, there you will not get these animals. They’ll be killed the majority of the time they appear in front of humans.

That’s so interesting, because I’ve been trying to collect stories about that. There are caracals in Cape Town, South Africa, coyotes in Chicago, and pumas in Greater Los Angeles, lots of animals in Rio de Janeiro like you said. To me, I find that very hopeful, that in a world so dominated by humans, these amazing creatures can live alongside us without really hurting anyone.

It’s very tricky, but you’re so right. For me it’s a story of hope. In the Anthropocene, these animals don’t have a choice, they have to adapt. But that’s a problem, because only the highly adaptable ones will be able to do this.

The tiger is going to have a really hard time, because it’s large, people will see it. But a leopard, even sitting, it’s so hard to see it. It’s easier for it to get away. Some habits and some characteristics of the animals allow them to be more adaptable, and these are the animals that will come live alongside us as we go ahead.

I believe there was also a finding that leopards in Mumbai might actually be protecting humans from dog bites by keeping the feral dog population low, and there’s actually a net positive human health impact of the leopard population overall. That’s fascinating to me.

So that’s not my work, it’s a paper by Alexander Braczkowski. It’s a theoretical assumption which is really cool. However, I don’t think it should be the job of the leopard to do what the municipality should be doing. Leopards can’t be your government for you! The administration needs to clean up feral dogs, not the leopards. It shouldn’t be expected of them.

Circling back to what you said about culture, you’ve written that people in many parts of Maharashtra have deep cultural and spiritual links to leopards, as exemplified by the deity Waghoba. Can you tell me more about that?

There’s a beautiful book called Icons of Power. Indigenous societies have always looked at these animals with fear and awe. Because they share space with these animals. It’s not just now, humans have been living with these animals for centuries. Why do tourists go to see these animals? Because they’re fascinating. And they’re fascinating even to the local people around them. It is there you find stories and myths, reverence and fear and fascination. But I think it’s only there in places where there is a shared history of space. When that shared history is gone…for instance in Scandinavia, for a hundred years there were no large carnivores. And in generations before, there were people who were paid to exterminate these animals. Their descendants are now being paid to conserve these animals. But in those intervening generations, the idea of sharing space had gone.

It happened in the British times in India as well, when these animals were viewed as vermin, there were bounties put on them. But in cultures where people have shared space, there is a relationship with this animals. It is not just a relationship of love, but also a relationship of fear, and it’s a negotiable relationship. What I’m finding across species, actually, is that people in India say that by having a ritual for these animals, the animals actually protect us. It’s some kind of-we haven’t been able to understand it, but we are finding it with crocodiles, the Indian bison, elephants, leopards. The sad part is, it’s only been documented by a few British and German anthropologists at the time of our independence. Ecologists and social scientists in India are only beginning to look at it. We don’t know much about it. We at WCS India have a project of celebrating nature-culture relationships. There’s a Coexistence Consortium which is looking at these relationships between wildlife and people It’s like in America, the Native Americans revered the wolf, but the colonials hate the wolf. So that’s where culture comes in.

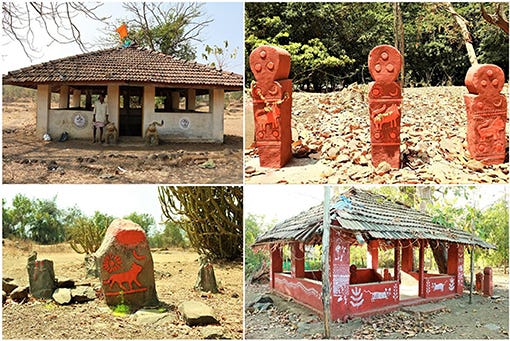

We’ve published a paper about the Waghoba shrines in the Dahanu Range, north of Mumbai. There are 168 Waghoba shrines, each village has a shrine. It's kind of cool, because we found another Waghoba shrine in a cave near Sanjay Gandhi, and it was incredible because we realized later that Ajoba, one of our collared leopards, signals from his collar had come right by it. He might well have been sitting by it in the daytime.

So one of your collared leopards went right by a shrine celebrating a leopard divinity.

A large cat divinity, yes.

That is so cool!

We published a little article about it. I'm not surprised. What we found with the collared leopards is that they love sitting among the rocks in the park to get away from the heat, in these rocky areas. People probably know that leopards are there. Is that whence the origin of the shrines came? I have no idea, but it’s not surprising.

That is amazing! Fascinating. I’ve also read some of your amazing stories of individual leopards in your spectacular booklet, Waghoba Tales. Can you tell me the story of the leopards Jai and Lakshai?

Okay, so I think we captured Lakshai first, and then we released her, and then we captured Jai. And we were surprised because the collars were giving us signals at the same time. We realized that the moment he left, they met up together, their locations were side by side. We did a genetic analysis and found that he’s probably her son. Even when she had her next litter he was with her.

Like an older brother.

An older brother, right. And one day, when she didn’t come back, for the day he was there in that litter site with the cubs. So that’s just amazing. And this was a hundred meters from a village! It was crazy That’s where she had denned. A hundred meters from a village. He used to actually sleep in a pumphouse, which was very cool with the mud. A shepherd opened the door suddenly and this leopard ran and jumped up a wall to get away, which was his usual way of coming and going. There was tin roofing material used as a temporary wall, and he tried to go through it. He cut his neck where the collar was, and because the collar was there, it didn’t heal.

And then one day I come to know that there’s a leopard in somebody’s house, and we go there, and it was Jai. I mean, it was incredible. People are sitting in the first room on the right in the kitchen, having their food. He was drinking water, and the kids started throwing stones at him, and so he went into the house. One person who was in the kitchen realized it, got up and locked the door, and took the entire family out. And then we got there, and he got into a trap cage.

He could have attacked the kids who were hassling him. He could have gone into the kitchen. I don’t know, I don’t understand it. I personally believe that causing a conflict between leopards and humans has disastrous consequences, and it benefits both parties, especially the wildlife, to not cause conflict, because they know how bad the retaliation can be from humans. To live in a landscape with so many humans, they have to learn to avoid humans, to not kill humans, because the consequences are terrible. Not just for them, for their whole society.

And they do have societies. A mother leopard and kids are together for two and a half years, the mother is teaching the kids. You also find, in other places, that the families are not in isolation. For instance, I remember, there used to be these tall sugarcane fields, and we used to know from the collar that his mother’s sitting in one field, and he’s sitting in the other field. Now just imagine if someone started hurting the mother. The son would know that someone’s hurting the mom. And what is the implication of that for the next human being that the son encounters?

We don’t think of these things. The mothers with cubs, oh my god, they must be so stressed. We only look at an attack made by a wild animal, and sadly we don’t have the information to understand why it attacked, when actually it’s so scared of human beings. Their first response on seeing a human is usually to run away. How do they [sometimes] get over that fear and go towards a human that they are really scared of? I don’t know how they do that.

So Jai was eventually treated by veterinarians? What happened with Jai after he got into the house?

We got him out, and then for nearly a month we treated him, and then he was released. So he was fine. It was actually fortunate he went into that house, because if he hadn’t got treated, he would have died [of the neck wound].

So what is the current state of your leopard research today? Did you have to stop due to COVID?

We had applied for permissions to put satellite collars on leopards in Mumbai. To get permission from the government, it took us four years, and it came just after COVID! We had to work during COVID. We collared five leopards in Mumbai. First one was done in 2020, the second batch was done in 2021.

Are you still tracking those leopards now?

The team in Mumbai is still working, but the collars all fell off [intentionally]. So we are no longer trapping the leopards but we will be camera trapping in Mumbai soon.

What are your plans for research in the future?

I’ve now got an administrative role, I can’t do research much. But Nikit, my student, who works in Mumbai, is doing great. He will be continuing the leopard work. Another student who worked on leopards and elephants in West Bengal has just finished his Ph.D., and he’s got a job. All these students will be going ahead and doing their work.

What are your thoughts on the likely future of the leopard population in Maharashtra and Mumbai? There’s so many different things happening. India’s developing, making progress very quickly in infrastructure and human health and things like sanitation. And there’s huge heat waves happening, which has got to be stressful for the leopards. What do you think are the chances for keeping this balance of coexistence into the future?

I think India is right now at a really tenuous stage in the fate of wildlife that share space with people. The pressure on forests is at its highest, and there is a lot of change that’s happening in the countryside, with respect to freeways and other infrastructure. There also might be a cultural shift coming where people think we have too much of wildlife and we need to kill them. It’s kind of sad, because I think India is otherwise such an amazing example of how humans and wildlife can share space together. But I think these consequences can be mitigated, it has to be intensive, proactive, people-friendly methods. We only focus on the animals as a solution, as a mitigation measure. That is a problem, but it’s also how we are trained. We are wildlife biologists trying to deal with a human problem. All these things make it harder for us to maintain the shared spaces. We are sitting at a junction, where we can either go this way, like the rest of the world, or we can go that way, where we can still try and figure it out. It needs a lot of innovation and new ways of thinking. I don’t know if we’re ready for it.

What would you want to have happen? What would be your recommendations for people, not just in India, on the lessons other cities and cultures can learn from Mumbai about living with large carnivores? To share a landscape with these animals?

I think the first thing you need to do is to accept their presence. And once you accept it, then you can take precautions. It’s going to have some costs. For instance, if your children go out to play in the dark, once night has fallen, you shouldn’t do that with bears and leopards around.

I think the first thing is realizing that accepting these animals means lifestyle changes for us, so that we keep ourselves and our families and pets safer. It’s adjusting to the presence of someone else, something else. I think that is the main thing that is required. And from the administration, it requires a proactive strategy to help humans so that the losses are minimizes.

Because all the focus, you realize, is on animals. Killing, translocation, sterilization. But they are not the problem, the problem is the humans that do not want them there. And there are reasons why the humans don’t want them there. So dealing with the humans, getting them to accept it after they understand all the possible problems, making them part of the solution, is super important. What I’m saying is those mitigation measures have to be people-centric and not animal-centric. Which is not done to a large extent now.

You should watch the video on YouTube called Living with Leopards, in Mumbai. There’s night vision videos of leopards in Mumbai, how they’re catching the domestic pigs and stuff. It’s really cool.

Thank you so much for sharing this. Is there anything else you’d like to share to readers? What should people know about the coexistence of animals and humans?

I remember in 2007, when I was quite new in this field, I met this scientist who worked with wolves in First Nation landscapes in Canada. It was quite amazing, because he said that the First Nations do not allow us to do any invasive methods with the wolves. And for me that was such an eye-opener, that people with a very strong culture and connection with this animal are deciding what biologists should do. That was an eye-opener for me, and I think that’s great. Because often we get into these societies without understanding how they view their animals, without understanding their history, culture, with respect to the animals we are studying. I think doing that perhaps gives you a much bigger picture of what human-wildlife relationships are in a shared space.

Wow. Thank you so much.

Such a positive story and a great outcome . Thanks