This is my fourth article based on in-person reporting from Mesoamerica. I completed this three-month trip in May 2025, but I’m still writing irregular articles about some of the fascinating people, wildlife, technology, and ecosystems I was lucky enough to see!

I was working from the city of Oaxaca in central Mexico when I was able to finalize a reporting visit on March 7, 2025 to the Yaguar Xoo sanctuary and conservation center run by the Jaguares en la Selva foundation in the rural areas outside the city. I’d been hoping to visit with these folks since I’d first read about their incredible work when researching my weekly newsletter in late 2024.

Jaguares en la Selva is a wildlife conservation and rescue foundation, caring for animals saved from the illegal wildlife trade — many of them delivered by Mexican federal prosecutors after being confiscated from organized crime figures. More than that, they’re running the world’s only “school for jaguars,” at their Yaguar Xoo sanctuary, working to rehabilitate and train captive jaguars to be wild animals again.

When I arrived (via the local colectivo informal buses) I was met by Sebastián Serafico, the sanctuary’s devoted veterinarian, who undertook to guide me around and explain the work they were doing.

First, we went to the main office, where Dr. Serafico walked me through the sanctuary’s history and context. The physical sanctuary was founded in 2000, and its closer connection with reintroduction efforts (and the origin story of the broader Jaguares en la Selva conservation foundation) took place in 2004. In that year, an indigenous community in Oaxaca State captured a jaguar that they believed had been killing their cattle but decided not to kill it, instead finding the animal spiritually significant and naming it “Grandfather Jaguar” or “the jaguar of light.” After fourteen months in captivity at the early sanctuary, scientists and researchers worked with the community to release this jaguar back into the wild in December 2005.

In the years since then, Jaguares en la Selva has provided a caring home for a lot of rescued jaguars (and other animals!), but their most dramatic and impressive accomplishment came with the rescue, rehabilitation, and release of two young female jaguars, Celestún Petén and Nicté Ha, which earned them the “world’s only school for jaguars” descriptor.

They came to the sanctuary in 2016 just a few days after being born, and conservationists seized the chance to try and figure out how to give them as close to a natural jaguar upbringing as possible — starting with an improvised “mother jaguar” made of a jaguar-print pillow and milk bottles.

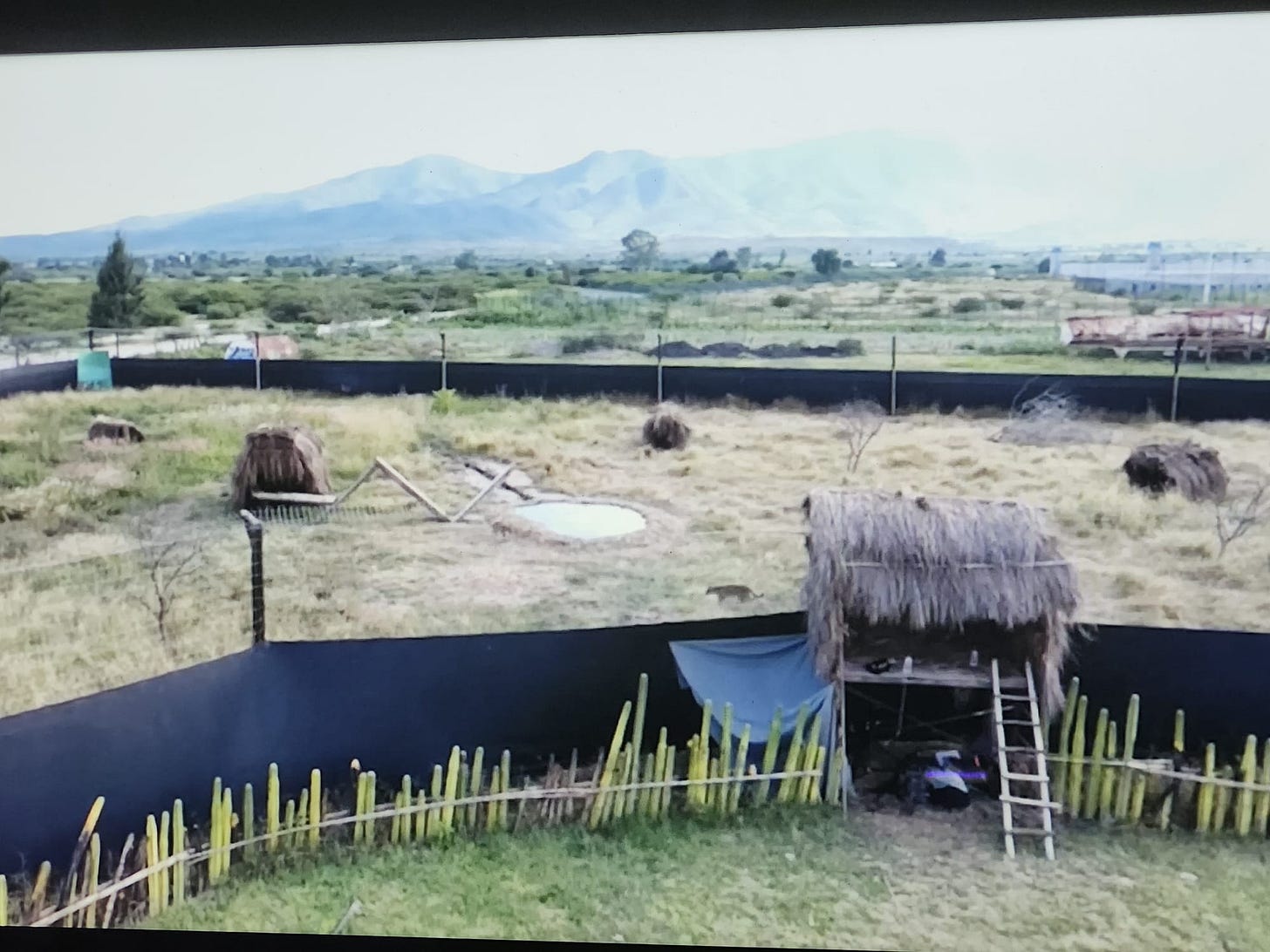

The sanctuary would eventually develop a unique, world-first “wilderness simulator” enclosure area, built to teach the young jaguars how to hunt while isolating them away from human contact, an ersatz version of how their mother would have raised them.

Grown to young adulthood with years of wilderness-simulator hunting experience, they were released into the wild in the jungles of Quintana Roo state in March 2021. The reintroduction was an epic journey in itself, beginning with a Mexican Navy plane flying the two young jaguars from Oaxaca state to the Yucatán Peninsula. Then, a team of scientists in pickup trucks drove as far as they could into the jungle, eventually carrying the crates full of jaguar deep into the interior of the forest balanced across two canoes through terrain that had been recently flooded by a hurricane. Their radio collars were set to automatically drop off eventually, and no human now knows for certain what Celestún Petén and Nicté Ha chose to do next.

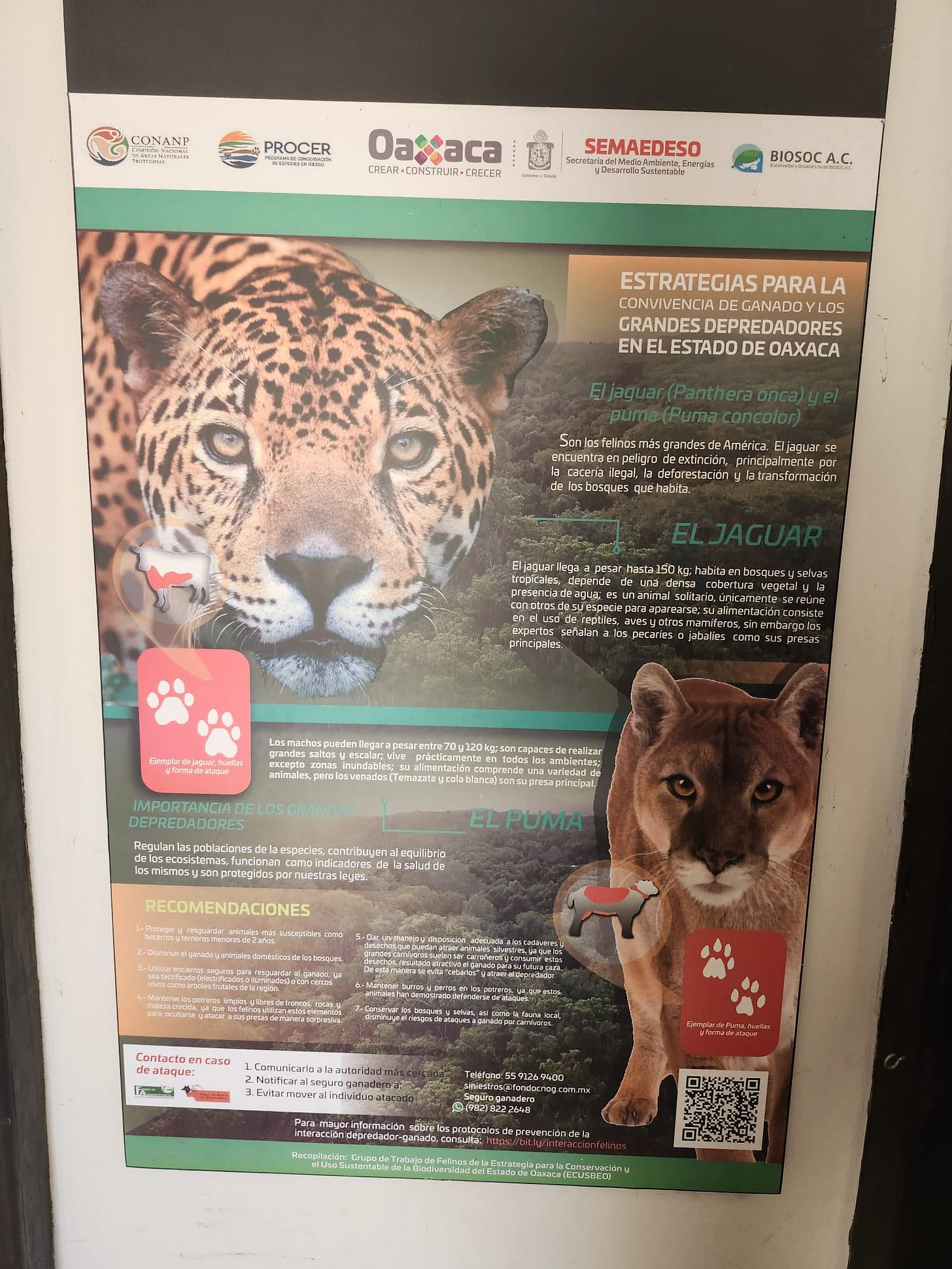

This bold stroke was only one of the ways Jaguares en la Selva works to contribute to the broader conservation picture. A far more “everyday” intervention was public environmental education, with busloads of schoolchildren and family visitors coming to see and learn about big cats’ importance to the ecosystem and methods of human/wildlife coexistence.

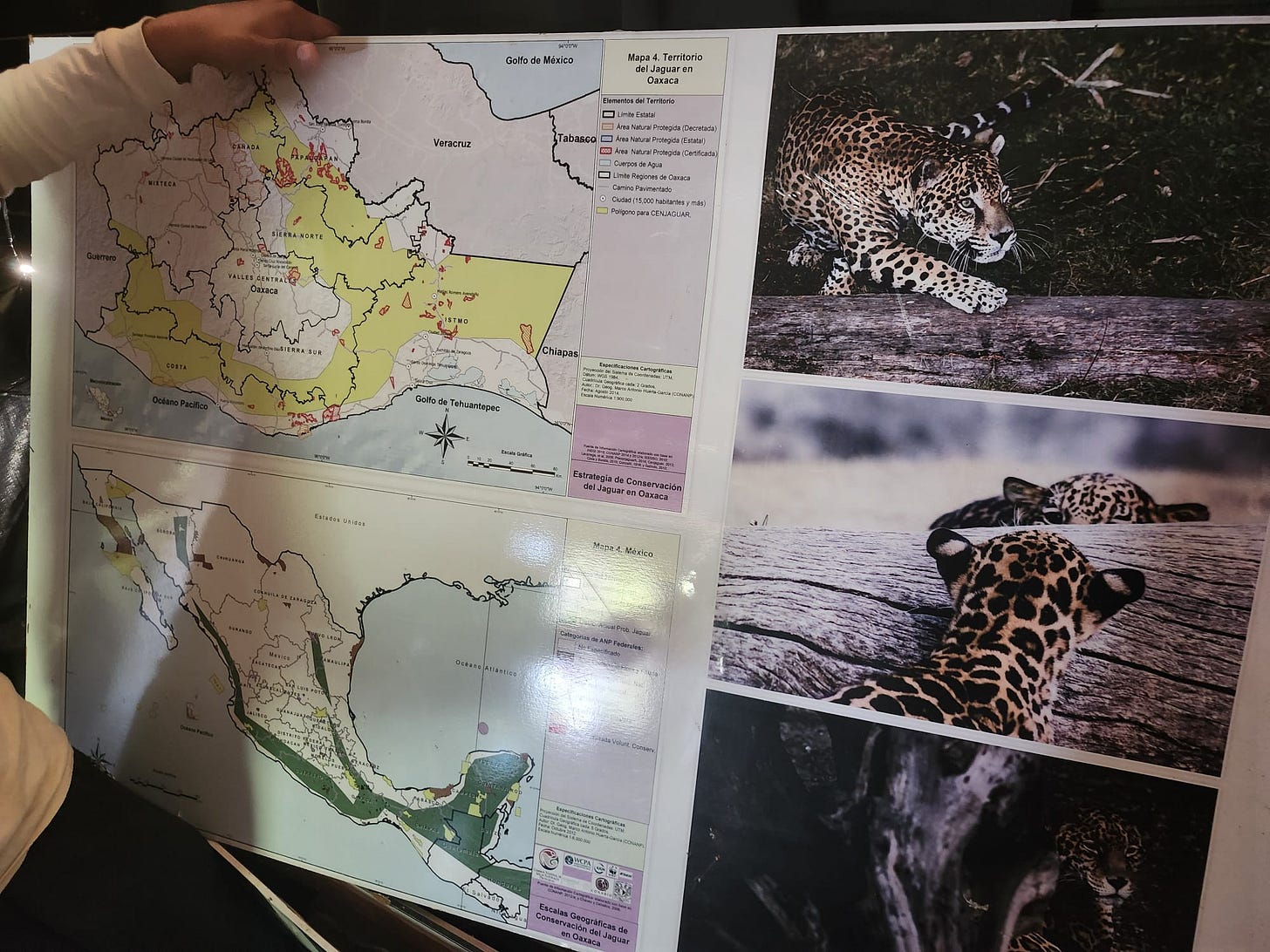

As of 2023 and 2024, there were an estimated 4,700 to 4,800 jaguars in all of Mexico, with the forested area around the tripoint of Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Veracruz states a notable hotspot. They’ve been driven locally extinct in El Salvador, Uruguay, and the United States of America, but have benefited from substantial conservation efforts in several other parts of their range from Belize to Argentina. Though the species still faces severe dangers (one particularly disturbing recent trend is the arrival of Chinese illegal wildlife traffickers in Latin America seeking jaguar body parts to sell as tiger body parts) they’re still among the big cat species with the largest wild population. (Check out the Weekly Anthropocene overview article on big cats). Since I visited the sanctuary, a new study incorporating updated density estimates in the Brazilian Amazon suggested that the total wild jaguar population across all its range is likely higher than thought, perhaps above 100,000 and possibly close to the high-end estimate of 173,000.

I was impressed to learn that this very sanctuary was building the world’s first jaguar genetic database. Sebastián showed us the gleaming fridge that housed DNA samples taken from hair follicles at negative 30 degrees Celsius, and told us of a new fridge on the way that would be able to cool to negative 80 Celsius.

Then, we left the office to see the animals in the sanctuary’s care for ourselves. Notably, several of them were actually “exotic” species not native to Mexico: though it wasn’t anyone’s original plan, these individuals had wound up finding their forever homes at the jaguar sanctuary because they were also rescued victims of illegal trafficking who had nowhere else to go and were welcomed by one of the few institutions in the area with the facilities and experience to care for large and traumatized wild animals.

Among the first we saw was an eleven-year-old Burmese python named Saigon, an absolute titan stretching 4.2 meters long and weighing over 65 kilograms. He was so reliably tame and sluggish that he was regularly taken out of his enclosure for public view, where he was easily handled by sanctuary staff and safely petted by visiting schoolchildren.

A little ways further along, an enclosure with several pools housed several tortoises and two sunbathing crocodiles, one of whom had been blinded by the chlorine in the pool where his previous illegal owner had kept him. Sebastián explained to me that the biofilm of algae that grew on this enclosure’s pond helped soothe and protect the crocodiles’ hides from further sun damage. Just beyond the pond, a few white-collared peccaries came up to the edge of their pen and grunted sociably.

Another enclosure housed a small group of spider monkeys (genus Ateles), from several different species with a range of black, red, and coffee-colored fur coats. They all shared an elfin gracile physique and a strikingly prehensile tail that absolutely appeared to be a fifth limb. Sebastián told us about how they were critical seed dispersers in their forest habitat, eating fruits and then planting new trees with their droppings. All the mammals seemed to know and recognize Sebastián easily, with many of them getting up and trotting to the fence’s edge at the sight of him.

Then we moved on to the big cats.

A second area was home to a female puma (Puma concolor, aka cougar) named Bulma, who to my astonishment got up and positively ran towards the fencing of her enclosure when she saw Sebastián, rubbing her head and side against the edges in just the way housecats do when they beg to be petted.

Sebastián explained that this puma had formed a psychological bond with him as a caregiver, and was now (with him, at least), so trusting that he could safely walk up to her and take blood samples without anesthetic or restraints. I was in awe that he’d established this level of trust while being this cat’s vet, the human who was in charge of administering sometimes-painful medical treatment. His gentleness with his charges was manifestly extraordinary.

Past the pumas, there were a multitude of rescued jaguars, but it was towards the middle of a very hot day (March is the height of dry season in Oaxaca State) and the majority of them were out of sight, dozing in shady nooks and dens within their enclosures.

I did get a glimpse of a family enclosure, home to a mother and her two now-grown cubs. Sebastián told me that these cubs had been born in the sanctuary, the product of a mating between a melanistic “black” male jaguar named Maximus (after the Gladiator movie) and a spotted female. They’d had two babies – one melanistic and one spotted. (“Black panther” is not a species name; it simply means any individual big cat born with a melanistic allele giving them a black coat. This can happen in both leopards and jaguars. Marvel’s Black Panther character is presumably named after melanistic leopards in Africa).

Another jaguar enclosure was home to Saori, a particularly sad story. This young female jaguar had had her teeth, claws, and paws badly mutilated in captivity, making it near-impossible for her to climb or hunt, and of course completely impossible to return to the wild. The sanctuary had developed a specialized diet and activity program for her.

The next jaguar we met was Link, a large male named after the classic video game protagonist. His teeth had also been damaged in captivity, making it impossible to ethically release him into the wild. Fortunately, he still had his claws and intact paws, and was able to enjoy climbing the trees in his spacious enclosure and faux-hunting exercises to keep him active. Link was by far the jaguar that I saw the most of during my visit to this sanctuary: many of the others were dozing or just didn’t feel like coming close to the edge of their enclosures, but Link was up and about, active and moving, giving us an excellent view of his beautiful form.

It was at Link’s enclosure that we were fortunate enough to see one of the enrichment activities the sanctuary provided to help keep their big cats active and healthy. (Here’s a video of Link climbing around his enclosure).

A large joint of meat (beef, apparently) was lowered into the enclosure on a hook-rope-and-pulley system, dangling several times higher than the jaguar’s height at the shoulder. Link stared at the meat, paused for an interminable-feeling few seconds, measured his distance, and then gracefully executed a gravity-defying leap, snatching the food down immediately in a single fluid movement. The very name “jaguar” comes from a Tupi-Guarani word meaning “the beast that kills its prey in a single bound,” and watching Link I could very much see why the name had stuck.

Beyond Link’s enclosure lay the “school” part of the “school for jaguars,” the spreading wilderness-simulation area with taller and thicker walls that didn’t allow views of the interior (except via cameras placed within). Sebastian told me about the “course” of wilderness training that Celestún Petén and Nicté Ha had completed, and that the current release candidates were undergoing. They started learning how to hunt for themselves with meat placed for them, then graduated to catching rabbits, then peccaries, then deer. Of course, we could not see the big cats undergoing reintroduction training – the whole point was to train them to become wild animals again, “de-habituated” to human presence and likely to run away if they saw a human. In the wilderness simulator, even veterinary check-ups began with a tranquilizer dart shot from a distance, so the “students” didn’t even see humans or associate anything positive with their presence. The current “class” being trained in the wildlife simulator consists of two jaguars, a brother and sister named Cachicamo and Lamanai (who arrived at the sanctuary as rescued cubs in March 2020 amid COVID chaos), as well as three pumas, Lontla, Sama and Dasai. The pumas might reportedly be released into the wild sometime later in 2025.

On our way back out of the park, I was excited to see several crested caracaras (Caracara plancus), the “bone breaker” falcon-like raptors of Latin America, landing on a wizened tree in the distance. Sebastian told me that they often visited the sanctuary to benefit from the fresh water left out for the big cats and regularly replenished.

The sanctuary was directly adjacent to an agave farm on one side, and there were many more in the area. Oaxaca is known for its distilleries of mezcal, a fiery traditional alcoholic beverage made from the agave plant. On top of everything else they were doing, the Jaguares en la Selva sanctuary is running a bat-friendly agave program, providing a “bat-friendly” label to farmers who left 15% of their Agave karwinskii crop to grow tall and flower so that bats could drink the nectar instead of harvesting it all before it flowered.

As I left the Yaguar Xoo sanctuary, I felt a surge of a feeling that has come to me regularly when visiting wildlife conservation sites: that this is some of the best that humanity has to offer. Our cruelty can be unfathomable, but so can our kindness. No other species in the world can boast individuals that would go to this much effort to try to repair harms done by their own kind to other animals. Furthermore, in this particular case they’re doing it at a nonzero risk to themselves — in October 2023, persons unknown invaded the Yaguar Xoo sanctuary premises during the night, stole a bunch of equipment, and set fire to the sanctuary office buildings. It’s still unclear who did this or why, but it’s possible it may have been some kind of revenge attack given that the sanctuary has taken delivery of many big cats confiscated from organized crime figures by Mexican federal prosecutors.

Nevertheless, the threat - if such it was - didn’t stop anyone for a moment. The Jaguares en la Selva foundation is made up of brave and good people, doing a vast amount of vital work with a stretched and shoestring budget. After what I’ve seen of their sanctuary, I’m sure that they’ll do their utmost to care for rescued big cats, safeguard their wild brethren, and train as many as they can to pass from one category to the other.

Notes from Oaxaca State

Here are a few more points of interest that stood out to me, in no particular order, when living and working in Oaxaca and environs in early to mid-March 2025.

Notes available for paid subscribers!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Weekly Anthropocene to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.