Interviews: Dr. Marianne Krasny, Civic Ecologist

An in-depth conversation on the future of food and more!

Dr. Marianne Krasny is a professor and the director of the Civic Ecology Lab at Cornell University. She directed the EPA’s National Environmental Education Training Program under the Obama Administration. Her most recent book is In This Together: Connecting with Your Community to Combat the Climate Crisis. Dr. Krasny also currently writes a column for Forbes magazine on climate action and is a volunteer with emerging startup Climate Action Now.

A lightly edited transcript of this exclusive interview follows. This writer’s questions and remarks are in bold, Dr. Krasny’s responses are in regular type. Bold italics are clarifications and extra information added after the interview.

This interview is syndicated by both The Weekly Anthropocene and Your Daily Dose of Climate Hope.

So Dr. Krasny, you're director of the civic ecology lab at Cornell. To start with, I just love that term, civic ecology, because public space and democracy and civil society is deeply linked to the ecology of the land we live on. Can you tell me what civic ecology means to you? What is a civic ecology lab and why are you leading it?

So the civic ecology lab, I'm going to just give you a little history. I worked extensively, starting in the 90s, with community gardens. Grassroots, often squatting efforts to take over vacant land in cities to produce something green and a space for socializing, basically. And as I worked in these gardens and did research on them, I found that a lot of times their value for the community was social. They provided a natural place for people to go be quiet and enjoy nature, but also a place to meet their neighbors. Growing food was also a goal, but not really the most important goal.

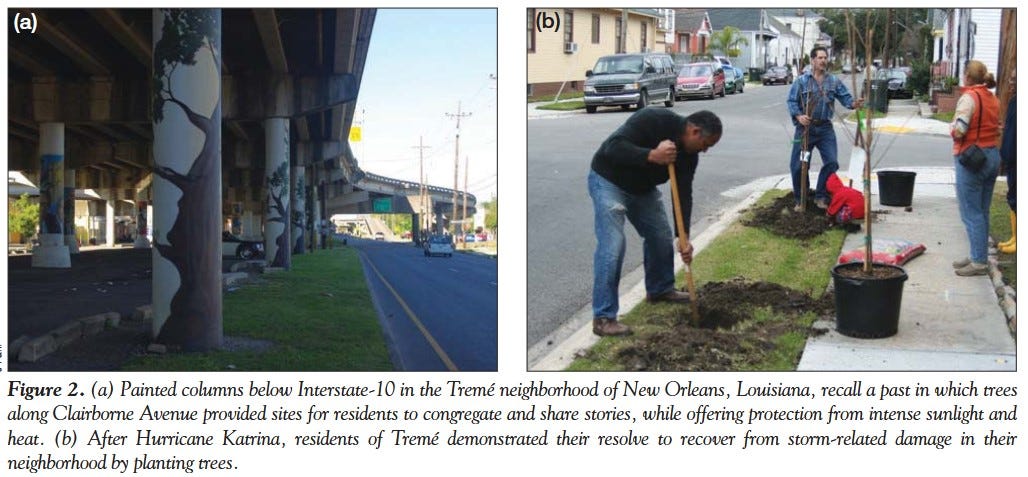

So then my colleague joined me to work on this, Keith Tidball. After New Orleans experienced Hurricane Katrina, he went down there and he was part of the Cornell Green Team who were going to do some planning with the city. He expected that people would be maybe looking at green spaces that were newly created by the hurricane and be planting gardens, and what he found was that they were planting trees. Which made a lot of sense in that trees are symbolic of New Orleans, the live oak trees with the Spanish moss.

Together, we thought, well, we need a name for this phenomenon, where in places in what was called slow decline, spaces become vacant and people are using these spaces. They're greening these spaces to give them more value for humans and nature. And also after sudden disaster, like in New Orleans, we're seeing the same phenomenon. That's where we developed the term civic ecology, to describe this phenomenon of people turning to green as a form of resilience after disaster or after decline.

That's a great way of putting it. In a world where it's increasingly hard to see the real, where the media environment has splintered, where AI hallucinates all the time, there is something just fundamentally real about the natural world that can really speak to people. Nature can bring people together. That's kind of what you're talking about?

Yeah, definitely!

One of the things that you've written about that's a major issue is plant-based alt proteins and plant-based recipes. I personally am a big fan of Beyond Burger, and I was really, really hoping that sort of plant-based meats could scale up and see the exponential growth that renewable energy has done. But they haven't quite yet.

It's strange to people. People are like, ah, this is creepy lab stuff, as opposed to the good old-fashioned sick antibiotic-pumped cow in a giant slaughterhouse. You get this weird dichotomy where people implicitly portray the existing industrialized agricultural system as somehow authentic or natural, when it’s really not.

What are your thoughts on that?

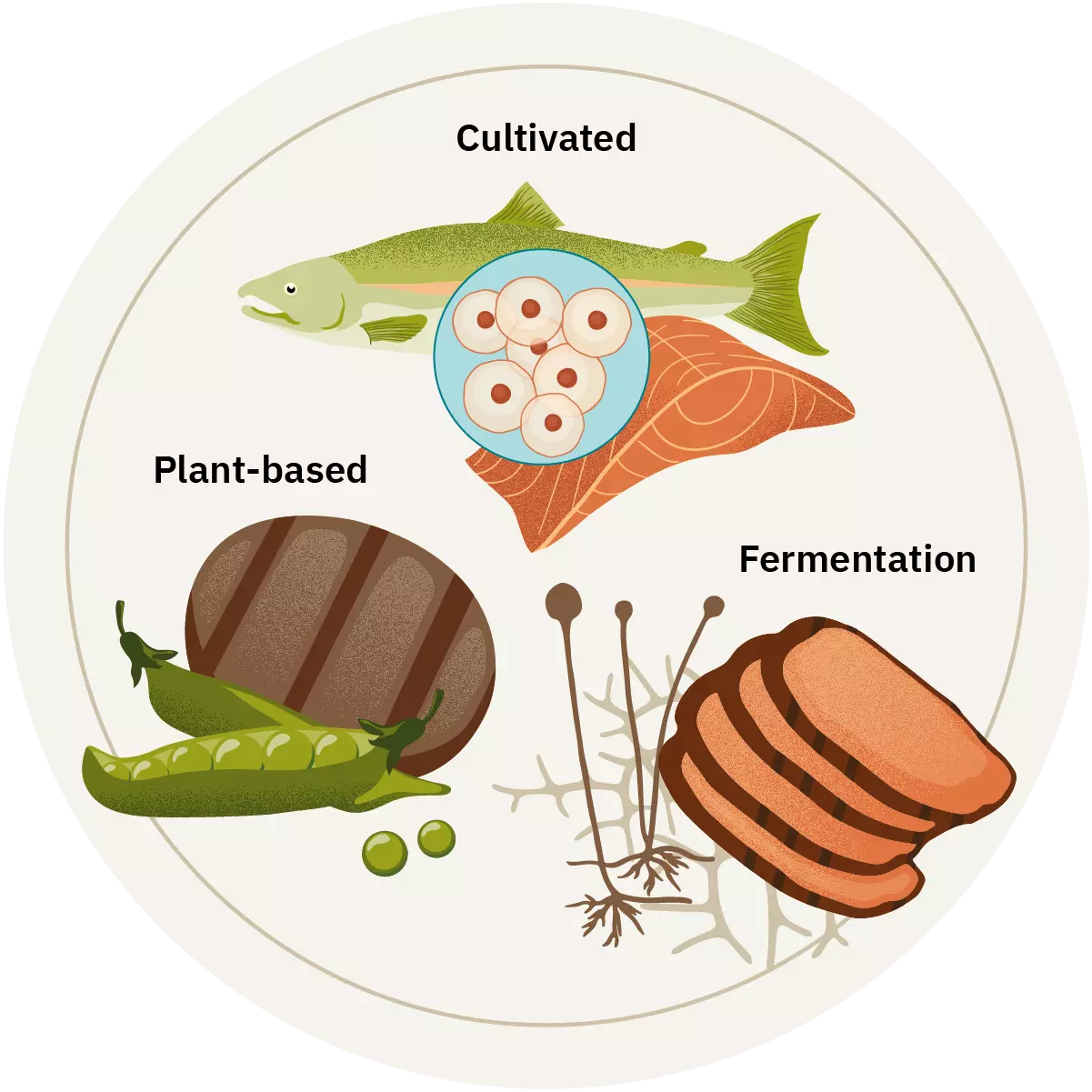

Really interesting. So I view alternative meats as a new technology, but it's also old technology, right? Tofu and seitan and so forth. But basically, these new forms of alt meats are an alternative technology.

In terms of them capturing the market, I think you might be a little unfair comparing them to renewable energy. I know you're tons younger than I am, but remember, Carter put solar panels on the White House roof and Reagan tore them down. Solar didn't just take off immediately. But as you've been pointing out, it may have reached a tipping point.

Alt-meats might be even a little harder for people to accept. To be honest, I personally don't have a desire to eat meat, so I don't eat Beyond Burger or those meat alternatives. Except for tofu. You know, eating is so personal.

Grandma isn't bringing you a homemade coal plant! That's what one of the people I interviewed recently said: there's a deep emotionality to food that there just is not to electricity. We've had electricity for like 200 years but food for all of our existence.

Right. Getting back on the economics and where it's going, if you look at the number of startups, it is just amazing.

True! There's definitely dynamism in the space.

There's a lot of dynamism in the space. There's a lot of new technologies.

I don't know if you've seen molecular farming as a technology.

Yes!

Yeah, so like inserting genes into the plants and then you grow the plants, then you extract the protein that the gene produces. It might be casein, so then you can have a dairy free cheese.

I was on a call yesterday with an agronomist, and he was saying that soon we’ll be able to convince microbes to just use electrons instead of sugars, and that’s a whole new solution.

I've heard a lot about that, actually. That's really fascinating.

But getting back to food and what people eat and “is this natural or not,” I don't think people are thinking about the ecology so much in terms of the ecological principles, right? They're thinking of this is food, this is real food, and this is fake food, probably. If you want to make the ecology argument, it's science, right? It's science. It's just using really advanced science, which of course, industrial agriculture is too. But I can see how people think, “this is real and this is fake.”

One thing I'm excited about with alternative proteins is that we can have the taste of meat without the negative impact.

But sometimes it seems like this is like a brilliant solution in search of a constituency, almost. People who care about the problems that it is solving are often repelled by the solution.

Right. I think that's a really good point. You know, I have a regenerative agriculture article in Forbes. The problem is, I see this all the time because I'm in a lot of different climate groups, everybody wants regenerative agriculture and they think it's going to solve the problem. It's not.

I just mentioned I was talking to a Cornell agronomist, he's been modeling global carbon sequestration or drawdown potential through regenerative agriculture practices. In the first place, there's so much variability, right? Some of these practices draw down carbon. Some of them actually release more carbon or greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Even if we were to use regenerative agriculture to its highest potential, his overall comment was that this is not a silver bullet, it's barely a buckshot when it comes to drawing down atmospheric carbon. Even if we implement the most effective regenerative agriculture practices globally, only 0.2% of current global emissions will be avoided. That said, we need to consider every buckshot in trying to bring down greenhouse gases, and of course regenerative agriculture has lots of other benefits.

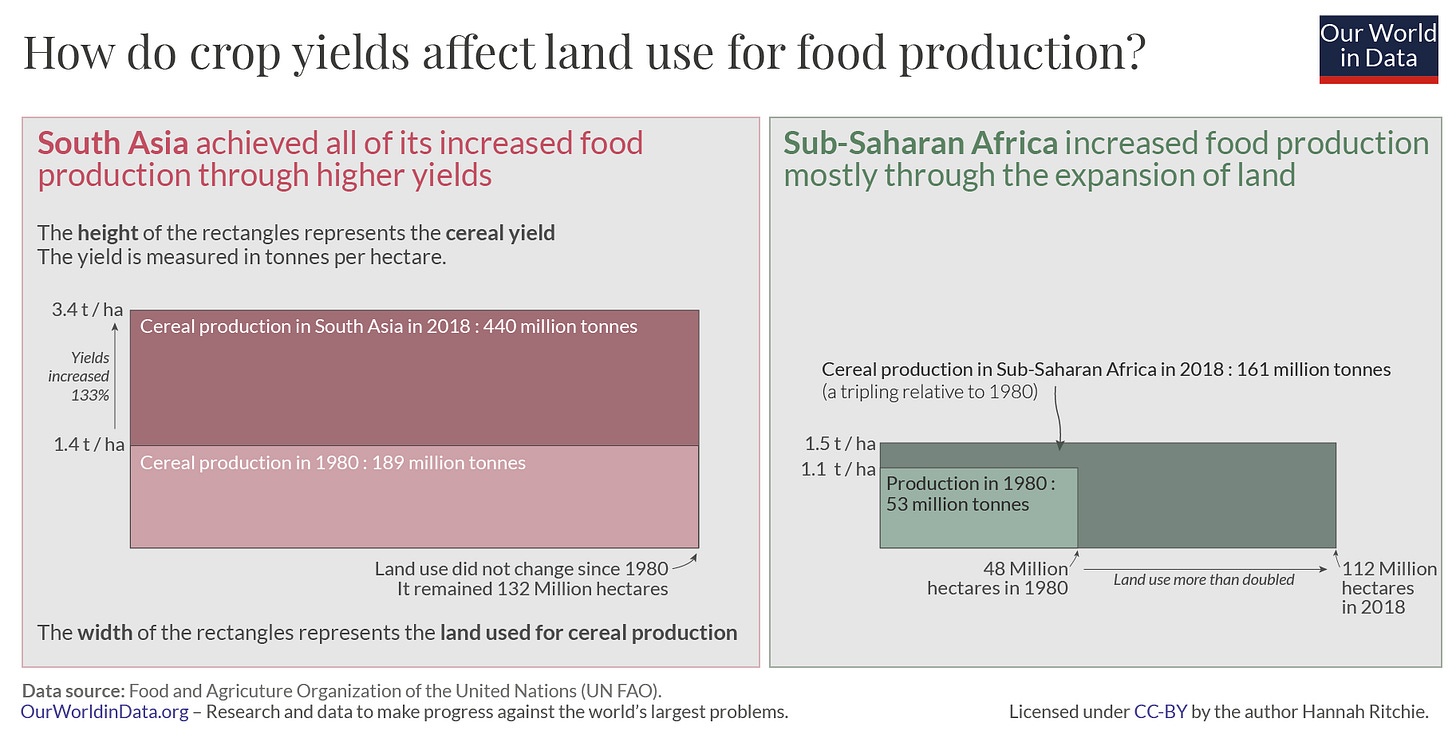

Yeah. Everybody can be like “Well, I don't like this thing in front of me, I’d prefer regenerative agriculture” and that sounds wonderful. But the heavy fertilizer-intensive sort of agriculture we have now, for all its many problems, is done that way for a reason, and the reason is it's generally economically the best way to get the most food out of a given amount of land, at least short-term. So sometimes regenerative agriculture could mean much higher land use and much more encroachment on natural habitats.

And pivoting too hard into organic farming can just be a disaster. I'm sure you've seen the news about the Sri Lanka disaster, right? In 2021, their government rapidly banned synthetic fertilizer, banned pesticides, banned all the stuff that people say they hate about agriculture. As a result, their agricultural sector collapsed, and they ended up begging for food from international aid. It was just a massive self-inflicted wound.

Regenerative agriculture is great on a small scale as a land management practice, but it's generally a really inefficient and expensive way to get food. There are these great projects like the Knepp wildlands in Britain that are producing beef in like a mixed wood-pasture system, where the cows have a great life and they promote plant growth and biodiversity and sequester carbon. I love that project, and it’s doing great things to heal the local ecosystem. But that's going to be really expensive beef!

Right. I mean, it's very sad because I think it has a lot of benefits. Pastoral landscapes look beautiful, plus have benefits for soils like decreasing soil erosion and building back carbon-rich soils, but it's just not the supreme climate solution it’s being proposed as.

Yeah. It's sort of counterintuitive, but more intensive agriculture, even though it often has really terrible impacts in terms of health and animal welfare, can substantially reduce environmental impacts just by concentrating them in a smaller area. If all our billions of people had to be organic subsistence farmers, we would probably have no wild ecosystems left on Earth.

We've actually hit peak farmland recently. The number of acres under cultivation by humans, after expanding for millennia, has peaked, and yields are still growing up. We're feeding people due to fertilizer and greenhouses and a bunch of stuff that means we get more food from less land. I find that really encouraging.

I’m personally vegetarian, but society-wise, I think that most people are not going to give up the taste and experience of meat. People are not going to go for only tofu and lentil salads. But one thing that I've been really encouraged by when I've traveled in Europe is the widespread availability of stuff that tastes like meat, but is plant-based. That's why I think that these alt-proteins are really important to deliver the hedonic boost of meat eating without the harmful impacts.

Maybe the way to think about it is, you could have a hamburger with half mushroom protein, half alt-meat protein? You're reducing the meat externalities, and in many recipes nobody would notice the difference. Like in ground beef, you know, it's going into spaghetti sauce or something like that.

So there's probably ways to infiltrate the market that aren't putting an alt-steak in front of somebody. And that's probably what we need to think about, as well as the climate carnivores who still want to have that taste of meat, but are concerned about meat impact on the climate.

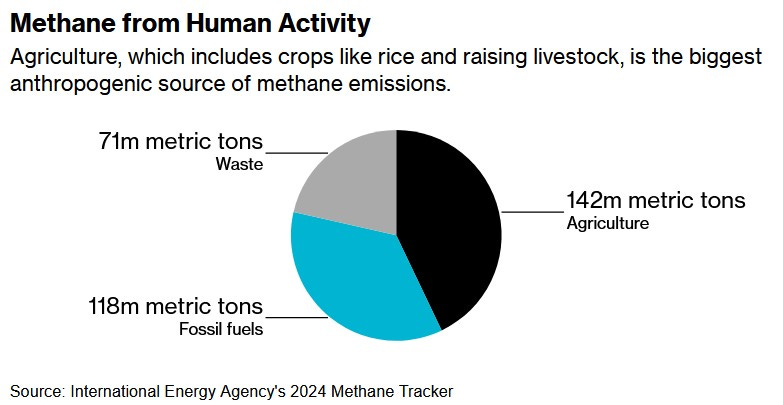

What other interesting solutions are, in your mind, on the way? I love your Forbes article about the potential innovations for reducing methane emissions from cows. People are going to be eating beef for a long time, even if we do come up with the perfect cell cultivated steak. Can you just give me an overview of the methane reduction vaccines, the genetic stuff, the seaweed additives, all that stuff you talked about in your article?

I talked to Cornell Professor Joe McFadden, who's one of the world's experts on this. He's working on feed additives in particular. He's working in India because they have very high dairy consumption and they have a lot of cows there, and he's trying to look at solutions that could be implemented in a place where the average farmer owns a couple of cows. Very different, very, very challenging. And he says that he thinks within a couple of years, there's going to be feed additives that are effective in reducing cow emissions and that are safe for humans.

The big one that's been approved now is Bovaer, from a European company. Its active ingredient is from a seaweed, aspergillus. That one seems to have pretty high effectiveness. He does think there's a lot of potential for feed additives within the next couple of years to make a significant difference in methane emissions, which is probably good news.

The others like the genetics, breeding, the vaccine, he says they’re further off. So he's seeing a 10-year horizon for those to come on the market and offer some efficacy.

There's adoption issues with all of these new technologies, but the vaccine is pretty easy if you only have to give it once or a limited number of times. The genetic breeding, you have to make sure the new breeds don't decline in productivity when they're bred for low methane.

Professor McBride thinks that eventually, you know all our cows are artificially inseminated by a limited number of bulls, those bulls will be tested not just for what kind of productivity genes they're passing on, but also what kind of reduction in methane emissions genes they're passing on.

These solutions are easier for cows raised in feedlots. For places like India, it's really difficult. Or other places where there's pasture-raised or non-feedlot beef, any of these additives are really difficult because the cows aren't being fed but rather they are grazing. Even in the U.S., a lot of beef might not be fed their whole life. It's a lot harder on pasture. And, of course, when people don't have big herds.

In places like India, McBride says what they can probably do is develop cooperatives, at least on the community or village level. Eventually, the village might have 100 or 1,000 cows instead of each person in the village having two cows. That could be easier for these management practices that are needed to bring down methane emissions.

One other thing I wanted to talk to you about was food waste. We have unprecedented agricultural abundance, but a really big chunk of the food that's produced by humans is wasted at some point between production and use, whether that's in restaurants or supply chains or households.

A new innovation that struck me as the most promising scalable effort against food waste that I’ve seen is this app called Too Good To Go. I interviewed them last year.

They are an app that rapidly connects you to places in your area like restaurants and supermarkets where they're about to throw away food, but it's still good.

I really hope that that can take off and become as much a part of global society as Airbnb or Uber, because it seems like that's aligning incentives. People want food, restaurants want to make even a little money off this instead of throwing it away.

So that's the best thing I've seen on food waste. What do you think are the promising avenues to reduce food waste?

There's also Olio, have you seen that app? I think it's more neighbor to neighbor than restaurant to consumer. Like “I cook too much, I don't want to deal with leftovers, come over.”

Now, obviously, these apps are getting to the most important food waste action that we can take, which is not wasting food in the first place, right? So we're using food.

And the other player in reusing food is, of course food donation sites. We kind of think of them as soup kitchens and we think of them as a place where we're feeding low income people, which we are, but it's also a really good way to reduce food waste!

So, for example, we have the Friendship Donations Network in Ithaca. I volunteered a couple of times for them, and we would go to our big grocery store, Wegmans, and they put out for us on the loading dock incredible amounts of food. It's amazing how much food they would be throwing out each day. When you think about it, they have prepared foods, where you can go through the line and you get a salad here or spaghetti there, going through and serving yourself. Well, they're not serving that the next day. It wouldn't be considered fresh. And that's going to our warehouse in Ithaca.

Fortunately, we have refrigeration in our warehouse in Ithaca, so we have a greater ability to store and redistribute food. A lot of these places don't have refrigeration, which is a problem. The Food Recovery Network nationally is organized for working with universities. So we have university chapters where our students are collecting food from the dorms or from the cafeterias and then transport it down to places where it can be redistributed.

Another really cool thing one of my students was involved in last semester is called the Freege network, for “free refrigerator.” This is actually an international network. The whole idea is, the student group got 12 refrigerators, they're trying to find buildings on campus where they can put the refrigerators, and then people can bring food and food insecure students or staff can go and take food out of the refrigerator.

And we have Good Samaritan laws. So obviously there's a lot of concerns in any of these donation programs about the contamination of the food. But for the fridge, the Good Samaritan laws would apply, which means that if I brought food that I think is healthy, I'm not trying to poison somebody, then I'll get the benefit of the doubt.

There's this article that I think you might enjoy in the food space from Our World in Data that’s titled “Increasing agricultural productivity across Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the most important problems this century.” Obviously to stop people starving, but also somewhat less obviously because increasing agricultural productivity generally has a massive positive impact on the environment. In places with really, really high agricultural productivity, like Europe and parts of North America, you start to see less farmland being needed and formal pasture and cropland returning to nature.

And in Africa, increasing yields to developed-world spec, or even South Asia levels, would mean you don't have to go out and cut down more forests or encroach on other ecosystems to feed yourself.

Just basic stuff, like genetically modified crops, fertilizers, stuff that often gets a bad rap in industrialized countries, is a massive improvement over what people might think is “more natural” old-school subsistence farming.

And speaking of genetically modified crops, this is an issue I’m really passionate about, so I’m going to go on a little bit of a tangent here. I think that the environmentalist left, of which I consider myself a part, has historically massively screwed up in their approach to genetically modified crops. Companies have done bad things with it, exploitative things, but the actual technology is incredibly useful and good. It's just a souped-up version of what we've been doing since the Neolithic Revolution in terms of altering plants' genes.

I'm sure you've seen the golden rice tragedy, where campaigns by Greenpeace and others prevented the distribution of a genetically modified rice crop that could have saved thousands upon thousands of kids from blindness just by having extra vitamins in the rice. I think this is kind of like the left's version of anti-vaxxer ideology. This is just full-on crazy.

And it's tough, because “genetically modified” sounds scary. It sounds sci-fi. People don't like to hear it. But supermajorities of basic crops like corn and canola in the U.S. are already genetically modified, and it's not causing problems. Africa and India could really benefit from using more genetically modified crops just for increased yield. Secondhand science-ignoring ideologies can often cause vast human suffering by preventing progress.

I think it's important to have a healthy skepticism about new technologies, whether they be regenerative agriculture or alt-proteins or GMOs. However, my general take on GMOs is…I lived in France a couple of different times, one was in the early-mid 90s. My friends were in Southern France, and my friends, who were very French left-wingers, they were demonstrating against GMOs. They were so against GMOs. And I kept thinking, you know, it's okay to be against GMOs — we didn't know a lot of the science back then — but you're really focusing on the wrong issue!

Right!

There's other much more important issues. Is it still a big issue, the anti-GMO movement? It was never that big in the US.

It's still way too big, honestly. If you look at the statistics on this, the opposition to GMOs has killed way, way more human beings than GMOs ever have. There’s blood on the hands of anti-GMO activists. I can show you the studies: opposing the spread of genetically modified golden rice, vitamin A fortified rice in South Asia, slowing that down and stopping it in some places probably added up to millions of life-years lost in India alone.

When there's a screw-up that atrocious even vaguely connected to any current movement, I think we have to not say, “but Monsanto,” we have to say, “Massive problem! We will do better.”

So I would agree with your point. I think we also need to keep our eye on Monsanto and whatever they're doing.

Yeah, but we have over-corrected so far on GMOs, anti-GMO advocacy has caused way more problems than anything Monsanto ever did.

Yeah. It’s the same thing with RFK, right?

Yeah, exactly. There's this sort of pseudo-scientific, faux-natural food ideology that adds up to just defending the worst parts of the status quo and preventing new solutions. With this trend, and it's really big in food advocacy, people end up saying essentially “The food system sucks, and also we will stop anything that might make it better.” Like, golden rice would have really, really, really helped. And plant-based meats might really, really help.

And you end up with a lot of people who care a lot about food and say they want a better food system fighting hard against those instead of fighting hard against feedlots or overuse of antibiotics or actual real problems like that. Does that make sense?

Yeah, it makes sense. But I wouldn't drop all skepticism or trying to monitor what the big companies are doing, right?

No, certainly that's valuable. But what I'm saying is there should be more openness to different kinds of food technology.

Absolutely. Different practices. Because yeah, big picture, right? We need to reduce emissions. That’s the bottom line. We need to draw down emissions. So we need to be open to any kinds of technologies that are going to help us do that.

Now, according to my colleague that I talked to yesterday, Dominique Wolf over in the School of Integrated Plant Sciences, he thinks that biochar has a lot of potential, but right now it's too expensive. And then, whatever we can do to reduce red meat consumption. Those are two of the big things that we can be looking at right now.

One of the lessons of renewable energy is that just funding a little R&D with federal money can really kick off a virtuous cycle of commercialization and adoption. Do you think that any jurisdiction right now, maybe a U.S. blue state, maybe a European country, could pull off an Inflation Reduction Act for food? We have the Farm Bill in the U.S., but now that's probably going to be stripped of most of its environmental funds. What do you think are the policy avenues to make some of these solutions cheaper?

Well, yeah, I really believe we can invest in some of these technologies and give them a foot up. If you look at Good Food Institute, I think they have some figures, there’s billions of dollars that needs to be invested to reach that tipping point.

GFI does great work!

I’ve been talking to Beyond Meat, the company, for my article. They said they’re working to get their products healthier, to bring down the levels of saturated fat and address the high levels of salt. They are adapting according to consumer preferences. This is a very dynamic sector. I don't believe they're going to go down.

There's this guy on Substack, Eshan Samaranayake, who has this newsletter called Better Bioeconomy. I think you'd really love it.

I try to cite his work, it’s really good. There's lots of fascinating stuff happening at the lab scale that hasn't been really commercialized yet. A company in Singapore just came up with a plant-based caviar that also has, a couple cultivated sturgeon cells in it for the taste, so there's no actual fish being killed, but it tastes like caviar.

That’s a luxury good, but that kind of thing in general, there’s all sorts of cultivated meats and seafoods that could attain mass scale.

You've seen that, the Attorney General of New York State, Letitia James, she's brought a suit against the big meat companies?

Oh, I didn't see that, actually!

Sued JBS, the world largest beef producer. I think the fossil fuel companies are becoming more risky investments. We'll see if that happens to meat. But anyway, she's trying.

And the other thing, just a little observation about the alt-meat industry. A lot of these companies, like the newer startups, when you go online and you try to find out what they're doing, it's almost impossible. They’re proprietary and they’re trying to get copyrights.

They're in stealth mode.

Yeah, they're not really trying to be public facing yet.

I am hoping that we're seeing that stirring under the surface, like you said, in alt-proteins that we saw in renewable energy in like the 90s. It's not big in the culture yet, it's not really taking off exponentially, but a lot of people are working on the solutions that will someday do that.

Well, hopefully it's going to be a super interesting sector to follow!

So, I got to go up on some of my hobby horses about stuff I think is important around food. What else would you like to share?

What I try to promote in my book, In This Together, is that we can have a lot of influence on our close social networks — that is, our family and friends. And you'll see in that book, a lot of research that supports this. I call it “network climate action,” network referring to social network. Regardless of whether you're taking a systemic-change action on the CAN app, or a lifestyle action, you can influence those around you to do it. You can invite your family or your friends or whomever to a plant-based meal, and share with them these facts from Our World in Data.

That's what I have my students do. They do network climate actions. I have a couple of videos of them. They're talking about it, and they really enjoy it. They might be sharing recipes at Thanksgiving, they might cook a vegan meal. And it’s not just plant-based food, there’s tons of other actions, like reusing clothing. Sometimes they choose a system change action, like working on transportation policy, and then try to convince their family to also send a letter to their city council member. What I try to promote is that we can have a lot of influence on our close social networks.

When I was in college, this student group I was with organized a huge free clothing market. Everyone brought their old clothes and you could take away whatever you wanted. People loved it, it was this huge community building thing. As you’re saying, food-related actions are inherently opportunities to build community, like sharing leftovers with someone who needs them or inviting people to plant-based meals.

You’re absolutely right that there's a great opportunity here to do environmental activism in a way that is also just an opportunity to meet people. To counter what The Atlantic is calling the anti-social century. [Here’s a library copy of that landmark article]. There's a great opportunity here to spread quietly positive messages on food and encourage people to try things that help the world, in a way that also just builds community and good times with people.

Right! That's kind of the nugget of my book, about network climate action. That's exactly what we're talking about.

That is great.

Is there anything else you'd like to share?

We did get carried away a little bit on food because of the writing I'm doing, but I think there's a lot of solutions. There's a lot of ways people can work with each other. The research shows that there is a big person-to-person influence we can have. This just happened: my daughter and her husband leased an EV, and when they did it, it really propelled me to finally do it. Then for me, I might influence my friend or another family member. We really need to think about the way these things grow from what we're doing.

Lifestyle actions, stuff does spread like that. Good ideas can be evangelized on a person to person level.

I really appreciate you putting the work into writing about this. Thank you.

Thank you.

This was a very illuminating interview! I am about 90 percent vegetarian and of that percent, I am about 10 percent vegan. I've a long way to go, but I really like the idea and reality of alternative meats. That beef rice from Korea is a brilliant idea!

“You killed people!” is exactly what all the libertarians and the like are now saying about Rachel Carson. Be very careful about the human entitlement of life against all trade offs.

I understood the dangers of GMOs very well in the 1990s (never had a problem with golden rice, did find it annoying to have fish genes in tomatoes), and what you failed to mention was that engineered canola and corn became fiat accompli across North America without consumer consultation or advisement, and these modifications and legal frameworks were to bake in pesticide use and a permanent market (or a permanent vanquishing of all pests, knock-on effects be damned). Non-client farmers were successfully sued for receiving the benefit of having such GMO farms in proximity, not so much for “well you have fewer pests now because they’re all dead” but for scattered 2nd generation plants from cross-pollination. Even since then, there are people who assert that organic farms are just free-riding on the proximity of conventional farms. Yes, you use less RoundUp overall when you’ve got a crop engineered to withstand the RoundUp. One way or another, the pests and their predators don’t stand a chance, and banks get used to their finance cycle, the farmers to their obligatory purchase and use, and the consumers to the products and prices of a monocrop world. Zero externalities were given any worth or value here. Consumer desire to adjudicate what to eat, and consumer’s desire to have a reasonably healthy concept of farming, was the only thing that got this problem onto the USDA and FDA radar — who both seemed or actually were entirely unconcerned with preservation of the natural world when I was coming up.

As for human health, in the 1990s we didn’t know how it would affect us, but that was also (I was there, I assure you this is absolutely the case) the only metric that was up for discussion, point finale. From local and regional newspapers (that, before they were decimated by today’s complete alteration of the media landscape, were de facto megaphones of their Chambers of Commerce) to metropolitan and national newspapers to *even student newspapers, I kid you not* was the following: “will organic produce cost you more? YES!!! Will it bring you any health benefits? NO! Ergo: Organic produce is a luxury good at best, and a scam for the rest of us.” Grocery stores put all non-GMO, organic food in its own special aisle so that it wouldn’t offend the choice sensibilities of all your average folks looking only for convenience and the lowest price. “Special” people with “special” needs could find it on their own. (And you know which chain, after Whole Foods, broke with that model? Walmart.)

Too often I see all old arguments trotted out (with greater sophistication and persuasion) as to why it’s even more important now that we continue with or else resume doing dodgy things that have brought us to this impasse (because, to the techno-utopian, it’s not an impasse! Who cares about continuity of the past, we want transformation!). But in places other than this newsletter, I fail to see any mention or much concern for the 70% of biota that we’ve wiped out in my lifetime, and the estimated 85% from the beginning of last century. All trade-offs benefitting human life have come at their expense.

Until about 2009 or so, every single business press article that was about any purportedly green technology came with an obligatory “tree hugger” sneer: a statement of skepticism and derogation of either the problem addressed by the new offering, or its ability to have any effect at all. It took a lot of collective will to rid us of this cultural tendency, which will always remain in muted form, as skepticism is part of the job of journalism and science. But this very newsletter would simply not at all have been possible without the earnest “idealism” and value-shift that let common people think bigger than their wallets and their stomachs.

I’m glad to see that there is a concern and interest in preserving what un-converted land we have left by making converted land more efficient, but governments don’t care about whose land and which parcel: conversions aren’t locked in stone until they’ve paved over with asphalt (while municipalities have a vested interest in making sure that happens!). Pretty much all land that’s not desert or rocky or a National Park is up for roll-over, if a populace can be persuaded it’s either a necessity or a foregone conclusion. Still, even people who are unsophisticated at forming arguments and have a hard time motivating themselves that if they stand up for something, it might have a bigger benefit than cost – which means most of us, really – even they can see issues as bigger and more holistic than the talk and the power moves that define the issue for them. Those people buying non-GMO or planting trees in New Orleans are expressing a need we all have: to preserve something recognizable to our antecedents. To put back what was obliterated. To only throw out the bath water, not the baby.