Interview: Wayne Hsiung, Animal Rights Activist

Towards a more compassionate civilization

Wayne Hsiung is a lawyer and leading animal rights activist, co-founder of Direct Action Everywhere (DxE) and the Simple Heart Initiative. He writes on Substack as

at . Mr. Hsiung is known for pioneering “open rescue” operations, such as rescuing Oliver the dog from China’s Yulin Dog Meat Festival in China, Rain the sick goat in North Carolina, Lily the pig from a slaughterhouse in Iowa, and many others. He was recently acquitted for rescuing two sick piglets from a farm in Utah, briefly incarcerated for rescuing abused chickens and ducks from a factory farm in Sonoma County, California, and was recently exonerated for rescuing a beagle from a research facility in Wisconsin.In the interview below, this writer’s questions and comments are in bold, Mr. Hsiung’s words are in regular text, and extra clarification added after the interview are in bold italics or footnotes.

Content warning: this article indirectly references mass animal torture, and contains links to explicit descriptions of horrific practices.

You’re fighting against factory farming, which is a really awful thing. When I interviewed you last year, I actually couldn't bring myself to finish the transcription and never published it, because the descriptions of the animal torture you've witnessed were so intense and horrifying. I think this is an example where "the ugliness of the problem sticks to the solution." People don't want to think about horrible things, so they don't engage with possible ways to make it better. I personally care a lot about animals, I've been a vegetarian for over a decade and I've donated and volunteered to animal rescue and conservation efforts, but I was put off from sharing your story last year because I didn't want to engage with the explicit imagery of torture. You're brave enough to do that, to stare directly at the awfulness, but I think the vast majority of people, trying to live their lives and provide for their families, don't want to and aren't going to. I hypothesize that the animal rights movement leading with the torture in public communications, which is really understandable because it's real and outrageous, might end up repelling more people than it attracts.

My newsletter's philosophy is that in a media environment that's often trying to horrify, shock, and disgust people, it can be more effective to share stories of progress, hope, and inspiration. And I think there really is a lot that's hopeful and inspiring about what you're doing: modern developed-world civilization is so prosperous and democratic (imperfectly, but at least compared to most historical civilizations) that we're willing to seriously try to extend our circle of moral compassion to animals.

Just a few hundred years ago, animal torture was considered family-friendly entertainment, from bear-baiting to goose pulling to dog fighting. Now, that's generally illegal and societally shunned, at least "in plain view" outside of the agricultural industrial complex, and there are people like you who are willing to put their freedom on the line to try and save the life of a dog or a chicken. I feel like that's kind of a good sign that humanity is growing as a species, maybe.

So I’d like to ask you, in this interview, to argue with one hand tied behind your back, so to speak: could you summarize the story of what you're doing, and your work, and DxE, in a way that focuses on the societal progress you're striving towards and the potential for better treatment of animals, without descriptions of torture?

All my work is built on the idea that humans are a compassionate species. We are also many other things—silly, short-sighted, cruel, and self-contradictory—but our large frontal lobes have given us a superpower: the ability to imagine what it's like to be another being, i.e., empathy. And while that power has been used for all sorts of despicable deeds—empathy can be used to manipulate, or to aid—it is fundamentally a source for good in the world.

“Humans are a compassionate species. We are also many other things—silly, short-sighted, cruel, and self-contradictory—but our large frontal lobes have given us a superpower: the ability to imagine what it's like to be another being, i.e., empathy.”

-Wayne Hsiung

What I'm trying to do - what the orgs I've started are trying to do - is normalize empathy. There are a lot of ways to do this -- storytelling, education, social contacts with those different from us -- but one of the most important ways is to simply model empathy ourselves. And what do you do when you feel empathy for a suffering being? You help.

Normalizing that sort of behavior isn't just good for the one you help, though, but for reshaping the institutions that guide all of our behavior. Especially, the law. The law is the most important normative system that people are familiar with; there's evidence that people will do all sorts of things, even vile and evil things, when the law (or some other source of authority), commands them to do so. So what we've tried to do is find situations where the gap between what the law commands, and what people intuitively want, is largest -- and then jump into those gaps to transform our legal institutions. This doesn't even require formal legislation, often. Sometimes, it's just the change in the meaning of a word. "Equal protection." (Gay rights) "Citizen." (Women's Suffrage) "Person" (Animal rights?)

These relatively small shifts in legal understanding have the potential to create immense change because they create feedback loops throughout the system. And these start in concrete cases, that illustrate why the shifts are not just reasonable but morally required. The prosecutor in our Smithfield case, for example, emphasized a sick piglet is like a dented can; for most people, that's a horrifying comparison because we know a piglet is a living being. The simple shift in legal understanding, however, from a piglet as a thing and a piglet as a person has dramatic implications beyond saving one baby pig.

Our primary goal is to effect these shifts -- and bring about those dramatic implications that could save billions of living beings from suffering.

“The simple shift in legal understanding, however, from a piglet as a thing and a piglet as a person has dramatic implications beyond saving one baby pig.

Our primary goal is to effect these shifts -- and bring about those dramatic implications that could save billions of living beings from suffering.”

-Wayne Hsiung

I absolutely agree with your goal of inspiring empathy and changing our civilization's view of animals as things. I became a vegetarian as a small child, right when I learned that animals were killed to produce meat, because I too believe, then and now, animals are non-human people, not things.

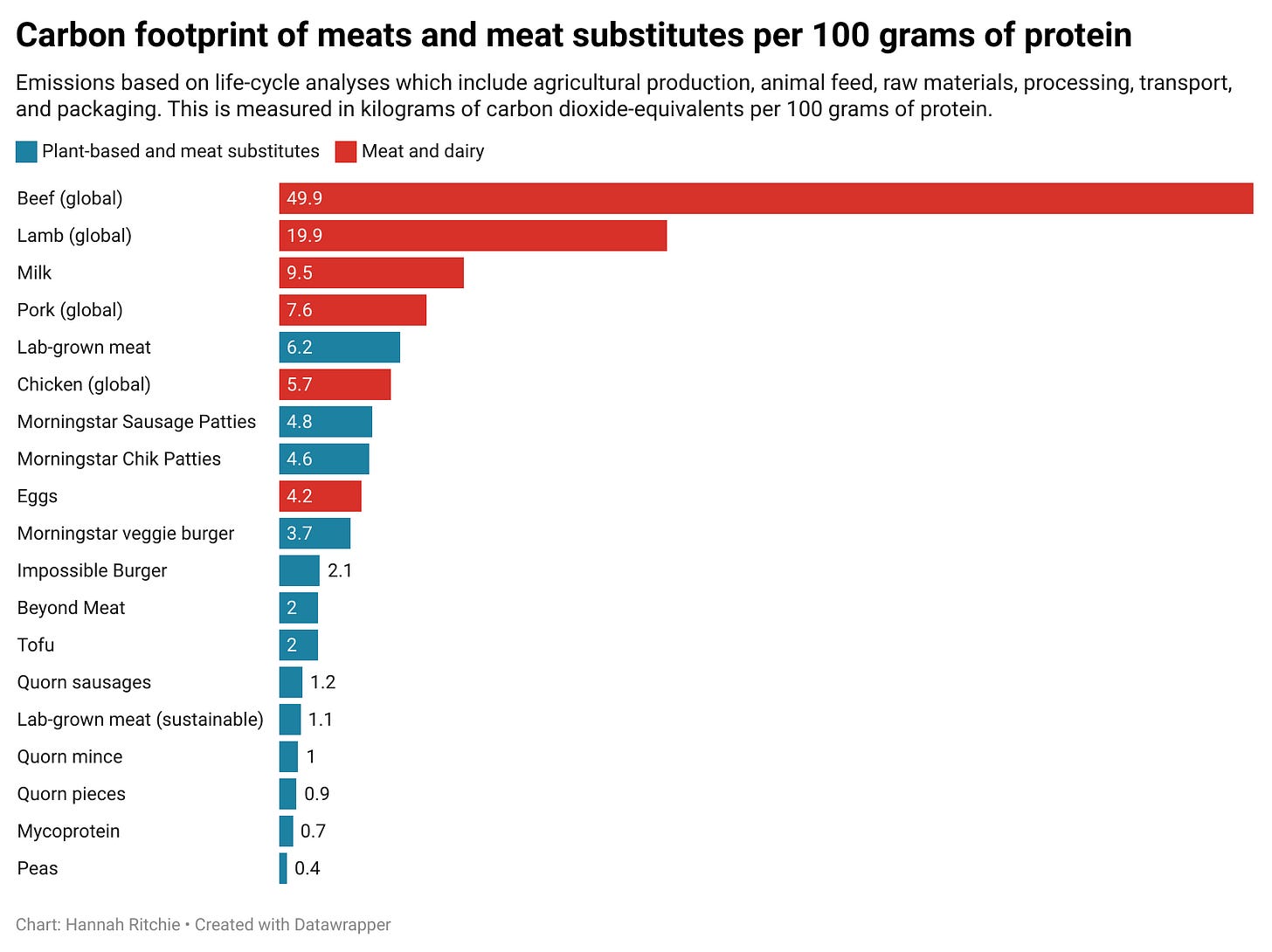

However, as an adult I've grown both more optimistic about the possibility of feeding humanity without animal abuse and elevating animals' moral status in our society and, paradoxically, less optimistic about the possibility of accomplishing this with moral argument alone (i.e. "converting everyone to traditional veganism"), however justified and true the moral argument. These two changes in my thoughts on this have the same cause: the rise of really good "meat substitutes." Right now this is mostly plant-based meats, like the Beyond and Impossible brands in America and La Vie in France, but lab-grown "cultivated" meat from cell samples is also a fast-developing field. On Substack, the "Better Bioeconomy" newsletter by Eshan Samaranayake is a spectacular fountain of information on the amazing advances happening in these fields around the world.

So basically, I'm really, really hopeful that cruelty-free but traditionally "meaty-tasting" meat is a utopian path forward for humanity's food systems. My personal experience has really been encouraging. I recently tried La Vie bacon, the first time I remember ever having bacon, and it was delicious. I suddenly got all the bacon-obsessed Internet memes. It helped me understand how strongly people can be motivated to wish away/ignore factory farming. I felt really good about the fact that I could now have this taste, but made from plant proteins and not horribly tormented puppy-like pigs. Plant-based meat is an accomplishment that makes me proud of our civilization and excited about our potential.

This emerging suite of "no-kill meat" technologies is really my biggest hope for the future in the animal rights space. Many people are already very empathetic and wish to see animals as people, but uncomfortably accept the knowledge of factory farming's many abuses because they're not willing to give up the cultural heritage and personal pleasure associated with meat dishes. I think it'll be a *lot* easier to get people to oppose factory-farming if it doesn't mean giving up (or even paying a higher price for) bacon, cheeseburgers, traditional family dishes, etc. I think that if we can "backstop" the moral argument with abundant, cheap and tasty plant-based meats to prevent a sense of sacrifice and loss, it will magically become a lot easier to convince people that animals are deserving of empathy and personhood.

Building on this, I wonder if the animal rights movement should invest more time, energy, and "narrative space" generally in supporting no-kill meats, perhaps by pushing for federal R&D funding as has worked out so well in growing clean energy. (On the other hand, I worry that politicizing it would just polarize conservatives against no-kill meats even more than they already are). At the very least, though, I think the veganism/animal rights movement, including leaders like you, should strongly endorse/narratively embrace no-kill meat technologies. What do you think?

You're definitely on to something. I have said before I think plant-based meats are the way forward. And with the recent advances in cell-cultured meat, we may very well see a world where animal slaughter is a thing of the past, yet we still have the delicious foods that people so cherish for taste and nostalgic reasons. I actually think plant-based meats are already at the quality I would want in a meat product, but granted, I haven't eaten meat in a very long time, so I may not be the person to say so. So absolutely the closer the taste gets to the original the better.

The political question is tricky. Definitely these types of meat replacement products are becoming a flashpoint in the culture wars. You could look at that as a negative, or as a sign that they're worth taking note of. I think it's a good thing they're being discussed and talked about. I agree that the role of animal rights activists, and myself in particular, are to highlight areas we think would catch on to achieve animal liberation as quickly as possible. So yes, I do think it makes sense for more energy and effort to be put into promotion of those products.

Separately, this week we published a piece in the Harvard Law Review. Might be helpful for your writing/thinking!

Building off your Harvard Law Review publication, could you share with me what your vision of an ideal near- to mid-term animal rights future would be? What would have to go right to end factory farming in America by, say, 2050, and what could that look like societally, legally, and economically? How would we ensure that there's no disruption to the food supply? What would we do with millions and millions of horribly traumatized pigs and chickens? What could we do to help prevent "West Virginia after coal"-style economic downturn in "farm states" like Iowa?

Relatedly, here's another really encouraging story I saw: former factory farmers switching to mushroom cultivation to escape both the animal cruelty and big agricultural companies' "debt trap" business style.

My vision for a near to mid-term animal rights future would be that animals are recognized as legal persons, not property or objects, as they are currently in the law. That would require a number of legal developments, some of which could be accomplished in the very short-term, those being: our appeal in the Sonoma rescue trial, and the upcoming Ridglan trial. For starters, should an appeals court side with us in determining that Judge Laura Passaglia erred when ruling against our efforts to bring up the necessity defense, that would set a groundbreaking precedent.

In Ridglan, there are similar opportunities to bring a necessity defense, and argue that if animals are in need of help, we have not just the right but the duty to help them. You don't have a duty to help a dented can, because a dented can isn't a sentient being. But a ruling in our favor on the question of personhood will recognize that animals are *not* property, and are instead beings who are deserving of moral and legal consideration. That's only possible with a movement of people performing open rescues, triggering awareness and deliberation, and putting pressure on our legal system to recognize the standing of animals. The most extreme abuses -- including factory farming -- will disappear instantly once animals are visible to the law. But inching forward on standing for animals will also propel us on the path to greater change.

There wouldn't be a major disruption to the food supply because we already grow more food than we need, and feed it to the animals. We raise close to 10 billion land animals in the United States alone per year, all of whom must be fed and given water. Those animals eat and drink far more than 300 million people do. The food sector is constantly innovating, and we've seen a plethora of plant-based meats and plant-based milks and cheeses flood the market. So the change is already occurring, fairly rapidly. It would happen much faster if we would subsidize plant-based foods the way we subsidize animal products today. This is also the answer to your question about what we could do for communities transitioning out of animal agriculture. Most of these industries are heavily reliant on government assistance as it is. So that assistance should go towards transitioning them rather than perpetuating the problem.

“There wouldn't be a major disruption to the food supply because we already grow more food than we need, and feed it to the animals. We raise close to 10 billion land animals in the United States alone per year, all of whom must be fed and given water. Those animals eat and drink far more than 300 million people do.”

-Wayne Hsiung

Thank you so much for sharing that inspiring vision. Here's my next question.

You’ve written about the suffering of bristlemouth fish, and how really massive numbers of these deep-sea fish might be suffering due to climate change warming ocean surface water, leading to reduced ocean layer intermixing and less oxygen for them. I think it’s really noble to be concerned about that, but it’s also almost too huge and too alien for the human mind to really comprehend. Which raises the question of: how far do we extend our empathy? What are the outer limits of that circle of moral concern, if any?

New York City’s tap water is home to multitudes of tiny shrimp-like copepods, killed every time someone drinks it, and I find it difficult to be morally concerned about that. Many invertebrate species, from Aedes aegypti mosquitoes to dracunculiasis-causing guinea worms, are so harmful to humans that there’s a strong moral case to eradicate them. There’s trillions of bacteria in every human body. It seems almost prohibitively impractical to try to accord even minute moral status to them. And then we get into the very controversial ethical questions around wild animal suffering that humans have little to do with, from the end-Permian extinction event to a whale swallowing a school of fish.

To be clear, I totally agree that it’s ethically imperative to move away from factory farming and that we should treat animals as having moral personhood generally. I guess I’m just asking, how do you prevent that line of thought from spiraling outward into an almost Lovecraftian “suffering is inevitable in an amoral cosmos” worldview?

The key moral principle is that sentience, and not species membership, should define moral consideration. We may not be entirely confident that copepods are sentient. But fish and other vertebrates certainly are. And I do think it's incumbent upon us to take invertebrate sentience seriously -- by, e.g., examining those species and determining if they're capable of experience suffering. Most people believe some invertebrates, e.g., the octopus, are. This is why Washington banned octopus farming. We should err on the side of caution given the long history of discrimination towards "others."

Perfection can't be the enemy of progress. So I'm not too concerned about "suffering matters" causing us to give up on everything just because we can't be perfect. Human suffering is inescapable, too. That does not mean I'm entitled to go around caging and killing other human beings! And our efforts to be more compassionate towards one another, while imperfect, have driven immense progress. So it will be for animals, too.

“Our efforts to be more compassionate towards one another, while imperfect, have driven immense progress. So it will be for animals, too.”

-Wayne Hsiung

A more speculative question: what do you think of the idea that animal rights and animal legal personhood, or even movements to try to achieve those goals, are only socioeconomically sustainable in a developed, relatively prosperous and secure liberal democracy?

For example, much of sub-Saharan Africa could probably use more animal protein to avoid malnutrition. When I lived in Madagascar, you could see malnourished kids begging for food in the street in some places. We were working with critically endangered lemurs, and in a survival context that work really needed to be justified in terms of benefiting the community, with conservation, restoration, and ecotourism jobs and revenue. Any discussion of rights or personhood for food animals like chickens or pigs in that context was just off the table. Even though I think it's morally right to consider animals as persons, it's not going to seem that way in a community where kids are starving.

In a perfect world I'd love to scale up plant-based or cell-cultivated meat to provide cheap abundant protein for the entire world, but that's not going be cost-competitive in poor countries for a while, and in the short term it seems like development needs to be the priority to try to get to a place where the populace is out of "survival mode" and can even think about animal rights.

Basically, what I'm trying to ask is, what do you think of the statement “animal rights/legal personhood is the kind of nice, civilization-advancing thing we can have once we establish sufficiently economically developed, democratic, free civil society-having rule of law-following countries."

I personally think that that statement works as an additional argument for fighting for democracy and prosperity, an example of all the amazing compassionate advances that can be achieved by a free people with an abundance-generating civilization.

Let me try to break down the question into two separate questions. The first is what our priorities should be in trying to create change for animals. I agree with you wholeheartedly that starving children in Africa should not be a priority [in terms of fighting for animal rights, obviously they should be a priority for humanitarian reasons]. More generally, as you note, people with more privilege are generally more able (and perhaps therefore willing) to adopt practices that include some cost.

The second question is whether those with less privilege have a moral obligation to include animals in their sphere of consideration, regardless of whether it's currently strategic to focus on those cases. The answer to that question is just as definitively, Yes!

I would also distinguish, as I have since writing Boycott Veganism 17 years ago, that there is a difference between killing animals and consuming them. Both are wrong, but for different reasons. Consuming the body of a sentient being is a matter of symbolic or expressive harms; we should revolt against eating pigs as much as we revolt against eating dogs (or other human beings), no matter how much they suffered before they died. The act of killing, in contrast, is a direct moral harm that must be condemned with special force.

A final point: I would actually reverse your final proposition, that animal rights depends on a well-functioning democracy.

A well-functioning democracy depends on animal rights, in the following important way. Democracy, and all other functioning forms of social organization, have a natural entropy that cause them to deteriorate over time. Preservation of rights for even the most vulnerable is not just an ethical imperative but a crucial bulwark from allowing this deterioration to pull a civilization to fall apart. Metaphorically, the inability to depend the most vulnerable can be compared to a loose thread on a shirt; ignore it and inevitably the shirt will unravel. Or gaps in a Jenga tower; fail to refill it, and otherwise fortify the tower's most vulnerable parts, and the tower will inevitably collapse. Civilizational progress and robustness has depended on filling these gaps in vulnerability for hundreds of years. It is why human society is so much more stable, and safe, than it has been at any point in history. But animal rights is a just-as-crucial step in that progress. This is particularly true as we begin to imagine other forms of intelligence that may be far more powerful than us. Like animals, we too may soon be a "lesser intelligence." The survival of our species may depend on building ethical frameworks, and accompanying rules, that evolve beyond speciesism or intelligence-fetishism, towards a general principle that all sentient beings must be protected.

“The survival of our species may depend on building ethical frameworks, and accompanying rules, that evolve beyond speciesism or intelligence-fetishism, towards a general principle that all sentient beings must be protected.”

-Wayne Hsiung

Wow. That is a really powerful vision. I agree that protection of the vulnerable must be one of the core criteria on which to evaluate a civilization. Thank you so much for this interview, Wayne; you've clearly thought very deeply about this.

There's a lot to admire with animal rights folks like Wayne who practice what they preach and truly care about animals. As someone who does consume meat and is a hunter, I do get all ethical concerns around taking another life. It is the paradox of living though. Death gives way to more life. I don't wish to cause unnecessary suffering when I take another animals life, but I can appreciate taking part in that cycle and knowing that their meat will go towards feeding myself and others. People who choose partake in the killing for meat are generally not numb, unthoughtful monsters, but actually very thoughtful in their practice and connected to what they do. I think factory farming perverts this process by allowing us to become numb to the animals suffering.

Very thought provoking and important points. The animal personhood concept totally makes sense in the context of historical fights for women, blacks and gay rights. Alleviating the suffering of sentient beings is a noble societal goal.