Interview: John Matthews of the Alliance for Global Water Adaptation

"It’ll probably take us a century to just fully absorb the concept of resilience."

John Matthews is the Executive Director and cofounder of AGWA, the Alliance for Global Water Adaptation. AGWA is a “global network to develop, crowd-source, and mainstream the emerging practice of economic and ecological resilience, especially with regard to water management.”

In the interview below, this writer’s questions and comments are in bold, Mr. Matthews’s words are in regular text, and extra clarification (links, etc) added after the interview are in bold italics or footnotes.

I like your hopeful and positive approach.

Thank you.

I think it's really important to take a positive approach in these issues. I think one of the big insights that I've had in this space too is that the U.S. can be insular in how we talk about climate issues. We're really disconnected from the larger global discussion.

I'm trying to help with that. Every week I have a news roundup trying to share news from around the world, contextualize, stuff like that.

I would just say generally that the U.S. suffers from what I would call big country syndrome. I've been traveling a lot on climate adaptation and resilience issues for a long time. Big countries like Brazil, China, I'd say the EU as a bloc, they tend to have, I think, a certain selection bias and a kind of siloization.

There's some countries that have just the opposite, like South Africa, Australia, New Zealand. These are countries that inherently look outwards, on a wide range of issues, including climate change. There are a lot of things that are truisms in the U.S. that are just bizarre and irrelevant to the rest of the world.

Could you tell me some examples? Because I absolutely agree on this broad trend. I'd love to hear some specific cases that illustrate it for our future readers.

Well, a huge one is, I would say, actually, the relative importance of adaptation and resilience versus mitigation. And some of this is the way that the discussion developed. Like Al Gore, he was dismissive of adaptation from the beginning. He was one of the people that kind of initially took a tone that adaptation was giving up, that mitigation was the biggest and highest priority, and that working at anything else was a waste of energy. He's revoked that just in the past six months, but I'd say about 25 years too late.

But there's still that perspective. I find it actually deeply ignorant of how the rest of the world sees the need and urgency for climate adaptation and resilience.

I must say, I've found this too.

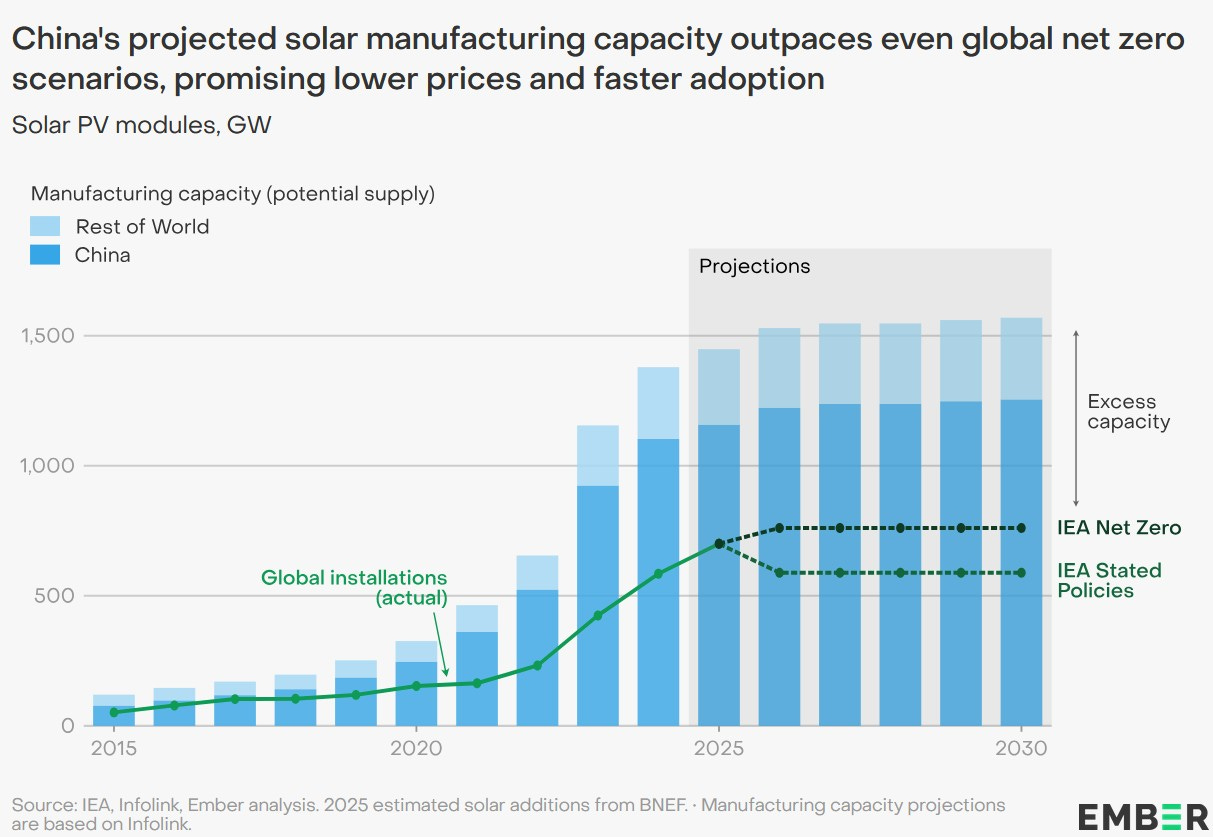

One could argue that the liberal, democratic, global, centrist, Western democracies’ plan to defeat climate change through international agreements, as articulated from the 1990s with stuff like the Kyoto Protocol, had totally failed but then China’s cleantech manufacturing showed up to save all our butts.

China's building vast amounts of clean energy that the Western democracies are not building. Efforts like the Inflation Reduction Act were great, but also both kind of too little too late, and then a reactionary backlash overturned much of that.

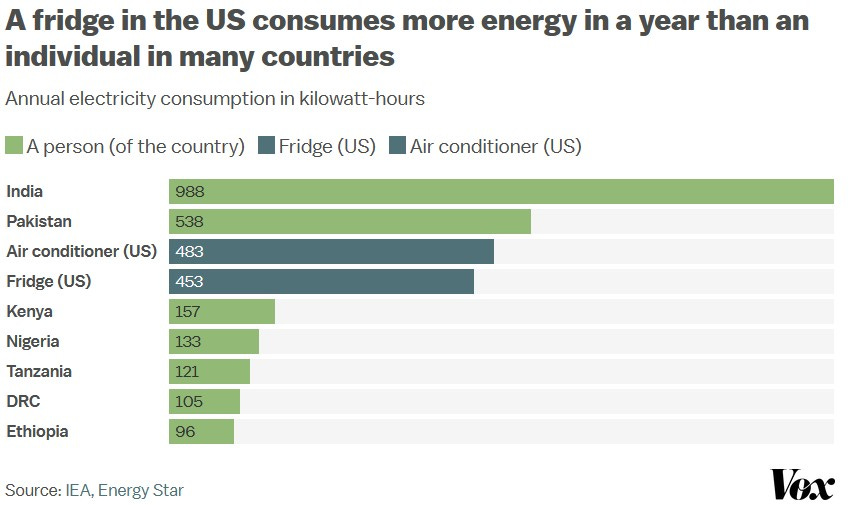

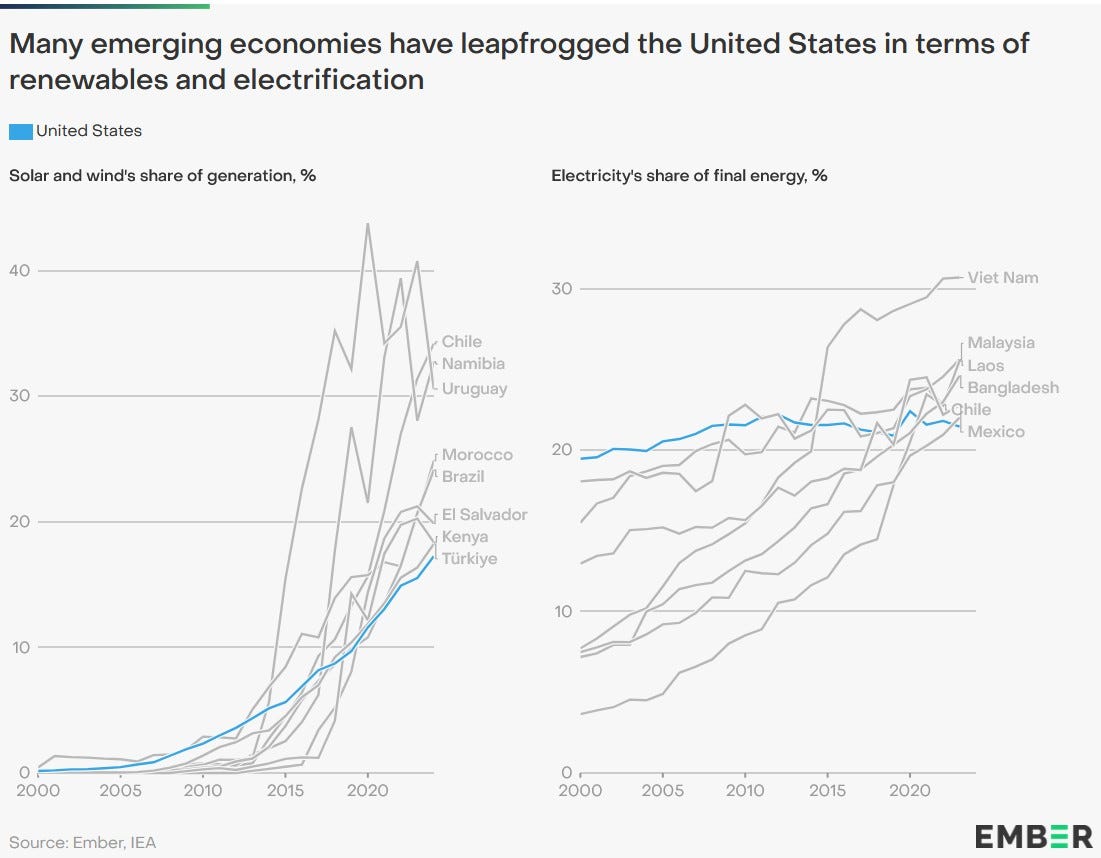

From what I've seen, the Global South is just in a totally different world on clean energy. It’s not primarily a climate-related thing at all. Emissions reductions don't matter to them — and nor should they! South Asia and especially Africa have absolutely minuscule emissions per person. They should not care about reducing them, they should care about making lives better for their people. Very fortunately for them and the world, clean energy is now the best way to do that.

I 100% agree with you. Why was USAID trying to get Nepal to shift to clean energy for home cooking, right? That was a major USAID grant. And it's like, Nepal is not even a rounding error in global emissions. There may be reasons to do it for quality of life and economic development, but don't put a climate mitigation spin on it!

Literally, 15, 16 years ago, I was in a World Bank session, and I heard a representative from Indonesia stand up and say, “Why are U.S. government and environmental groups trying to attack us for wanting to build one more coal-fired power plant, when the emissions from that particular plant are roughly equal to the amount of emissions associated with how much the U.S. emits drying its clothes each year?”

Yeah. We are just extremely lucky that the economics on renewable energy have shifted fast enough that rapid clean development is possible, China is seeing an emissions peak and even India might be seeing an emissions peak. Because the mitigation focused, emissions-reduction focused path just doesn't work, politically or economically. It just doesn't.

Yeah. It comes across as punitive, it's a kind of climate colonialism, and I think it's potentially counterproductive in the end. It messages to middle and lower income countries that we want to punish them for our emissions, and that we're not worried about the climate impacts that they are already experiencing or how they prepare their economies and ecosystems for the impacts already in the pipeline.

The really massively fortunate thing is that a technological revolution has overridden, in some ways, political concerns. China especially, and India and Indonesia, are now building lots of clean energy because it's the cheapest and best way to get development and electrification at scale. Not primarily because of the Kyoto Protocol or global climate talks or the things Western countries thought would drive decarbonization. Just because of the economics. New coal plants are increasingly sitting unused in India and China because you have to burn that fuel and pay for it and solar is cheap!

I think we agree on a lot of these issues, Sam. That's great! It's a counternarrative about the increasing importance of climate adaptation and resilience that really needs to be heard much, much more in the U.S., and really needs to enter the progressive, Democratic, moderate policy conversations here much more effectively. In fact, I think it's even aligned with the Democratic discussions about "abundance." Actually, I think even conservatives would buy into climate policy from an abundance and economic development perspective: we need to secure our economy, our cities, and our supply chains against the emerging climate impacts.

Maybe the most challenging truth is that these issues hold as true for rural Alaska or Appalachia — and Houston and New York — as they do for Nepal and Malawi.

We need to be making these kinds of economic development arguments based on whether or not they really improve the lives of people in those places! Climate risk is not just about the future or about poor countries. It's about everywhere and all of us and right now. And it's not just about reducing risk either. Climate resilience ultimately is about how we make our lives better, even as the climate continues to shift and evolve.

I personally feel — as someone that has been working in this space since 2003 — that the scientific literature tells me we're already committed to a lot of climate change for a long time. And that also expands our focus. Mitigation is absolutely important — that's taking your foot off the gas. But we're on an almost frictionless surface, and the vehicle's going to keep moving forward for quite a long time, probably centuries no matter how much mitigation we do right now. We need to think more about the airbags and how we're steering.

Absolutely.

Not just reducing climate risks. To me, it's about “How do we make sure that our kids have a better life than us despite ongoing climate change?”

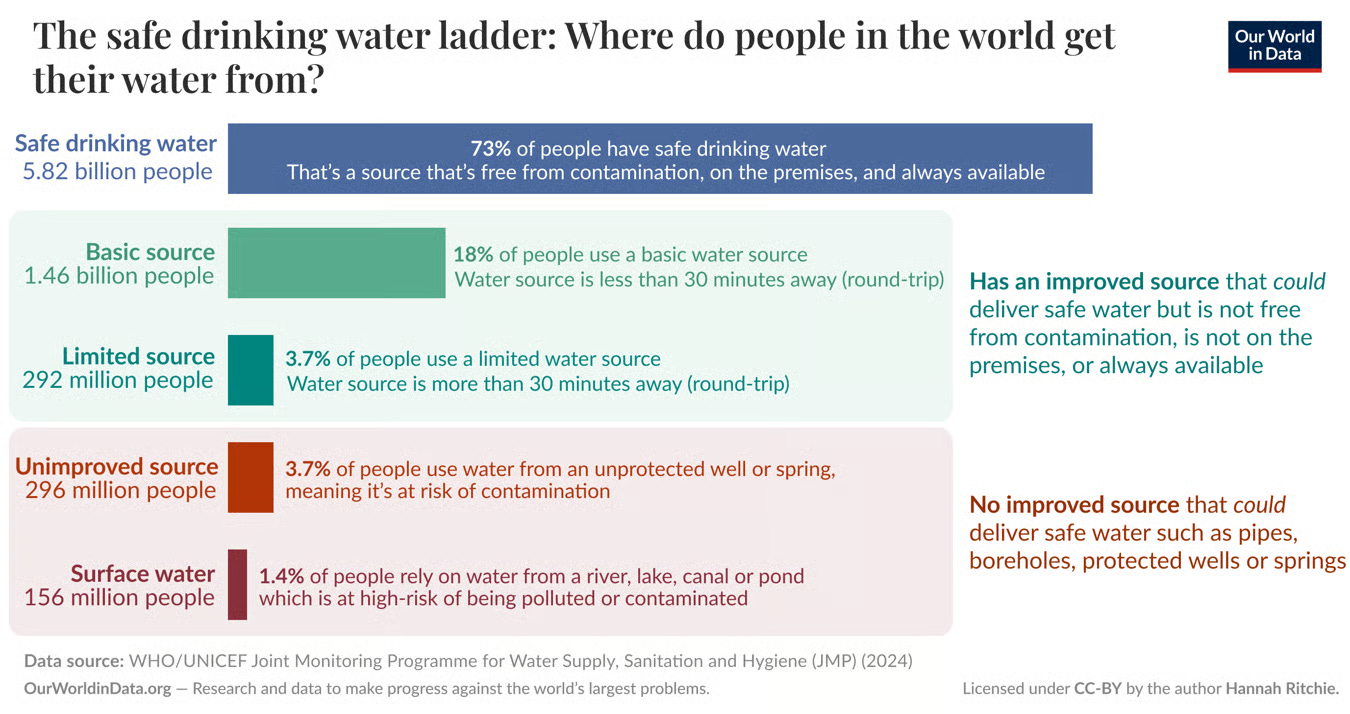

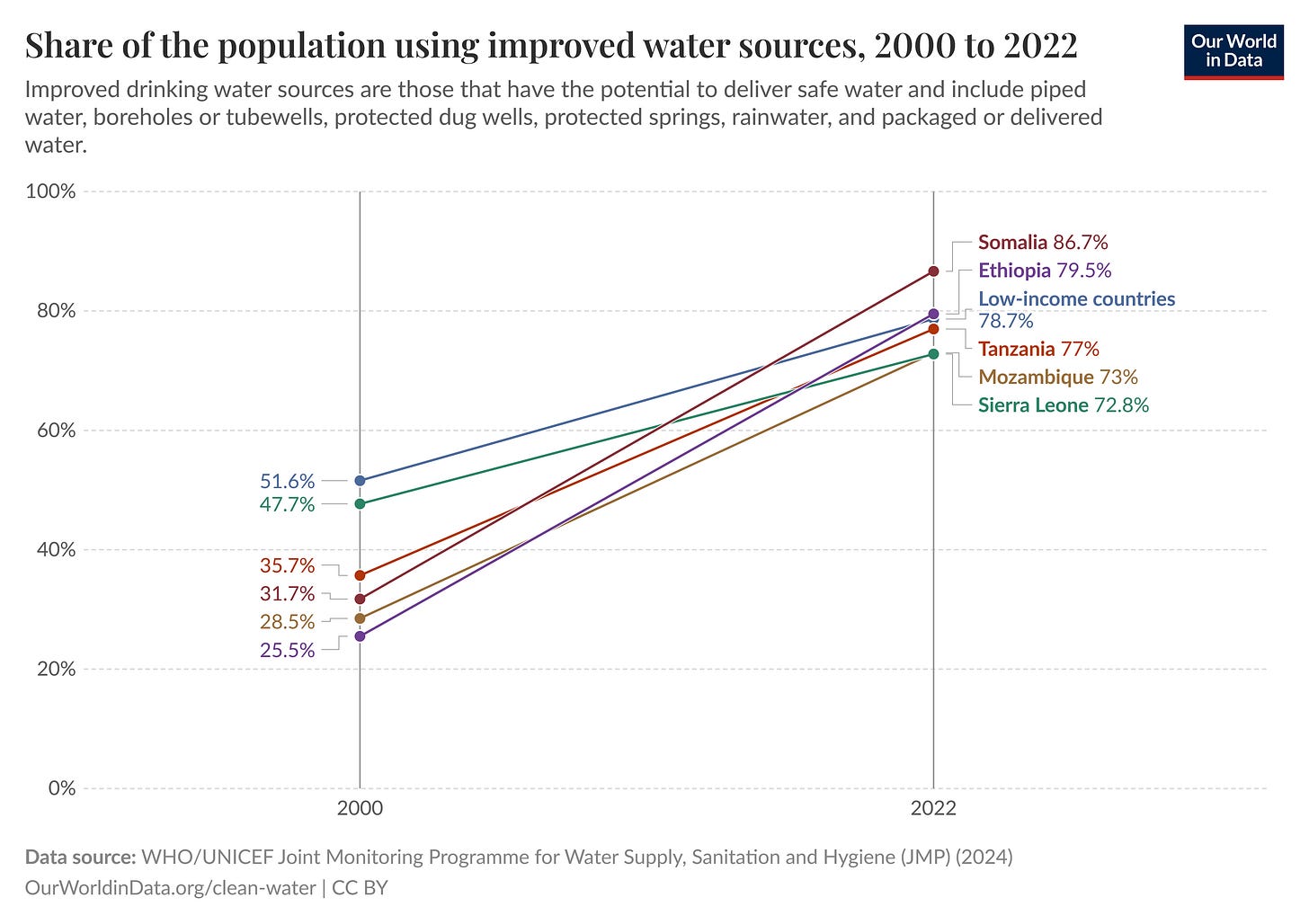

We clearly can do a lot of that. The recent WHO/UNICEF report on global clean water and sanitation progress calculated that over 2 billion people got access to safe drinking water since 2000!

Even as the habitat for malaria expands, we just invented malaria vaccines.

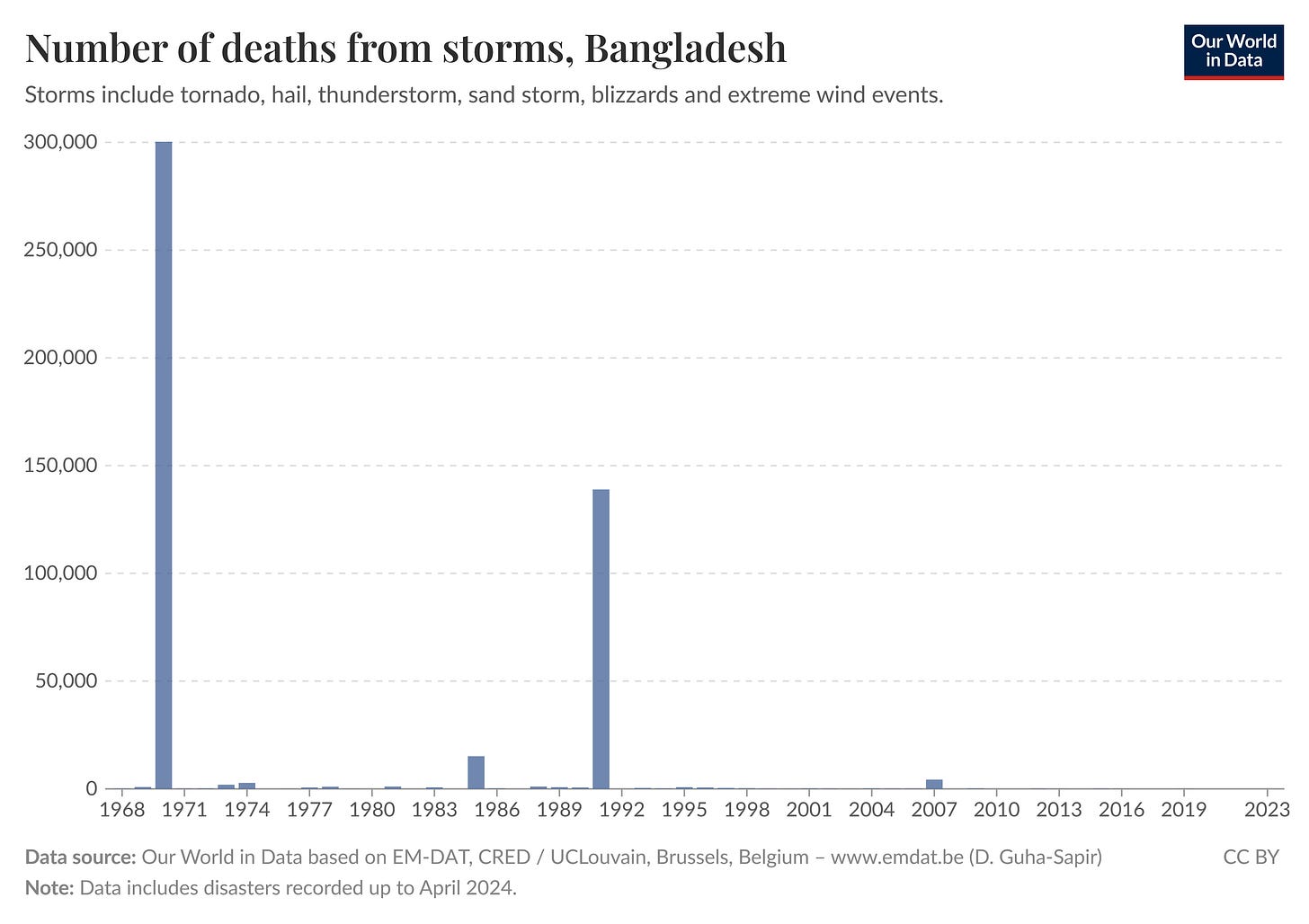

Bangladesh, when it got hit recently by a storm even stronger than that big one that killed so many Bangladeshis in the 70s, it had like exponentially lower casualties because now it has an early warning system and storm shelters. We are seeing successful adaptation on big important topics at scale.

Yeah! I totally agree. It's a different way of thinking about the situation. We're not going back to 1990 or 1970 or whatever, but that doesn't mean that we're helpless and we don't have a choice and and that we can't have good and even wealthy and happy lives. It means that we need to be thinking much more clearly and explicitly.

This is a brilliant framing, honestly. It's really one that I'm trying to do in all my writing. When I talk about clean energy, I'm trying to focus on how it's cheap, it's affordable, it's reliable, it's decentralized, all the benefits. Not about how it’s better for the planet, talking about how it's better for you.

Like, the current White House stopped this offshore wind farm. I write, “that's bad because it would have powered X hundred thousand households and lowered electricity bills,” not “that’s bad because it would have reduced CO2 emissions by this many tonnes.” We’ve got to be more relatable. The language I write with tries to focus on the economic development and personal well-being argument.

Well, kudos to you. I think that's coming through in the material that I've seen so far and I also think that you're right. There are positive signposts and mile markers, and we can be more ambitious about those, too.

Absolutely.

There is a framing around water that outside the U.S. has become a kind of truism. It's the idea that water is often the medium through which we'll experience negative climate impacts. Some people call water the teeth in the shark of climate change.

However, water resilience is a new idea. That's the concept that the water cycle should also be the medium for resilience itself. Most of our solutions for climate adaptation and climate mitigation are connected to how we're spending our water currency and considering the deep connections around water for energy, healthcare, transportation, disasters, forests and farms, really almost everything until you get to the blue water in the oceans. Water resilience is how we operationalize most climate action.

That conversation is not happening in the U.S. but it needs to be.

That WHO UNICEF report you mentioned on how much progress we've made on water access globally is one where I think if they were to write that in one or two years, they would probably write it quite differently. WHO and UNICEF are both undergoing what I would call a major adaptation and resilience makeover. I think significant parts of their staff and some of their programs are beginning to understand the nature of their work more broadly. There are also major water and sanitation NGOs in the space that do not collect kind of long term data.

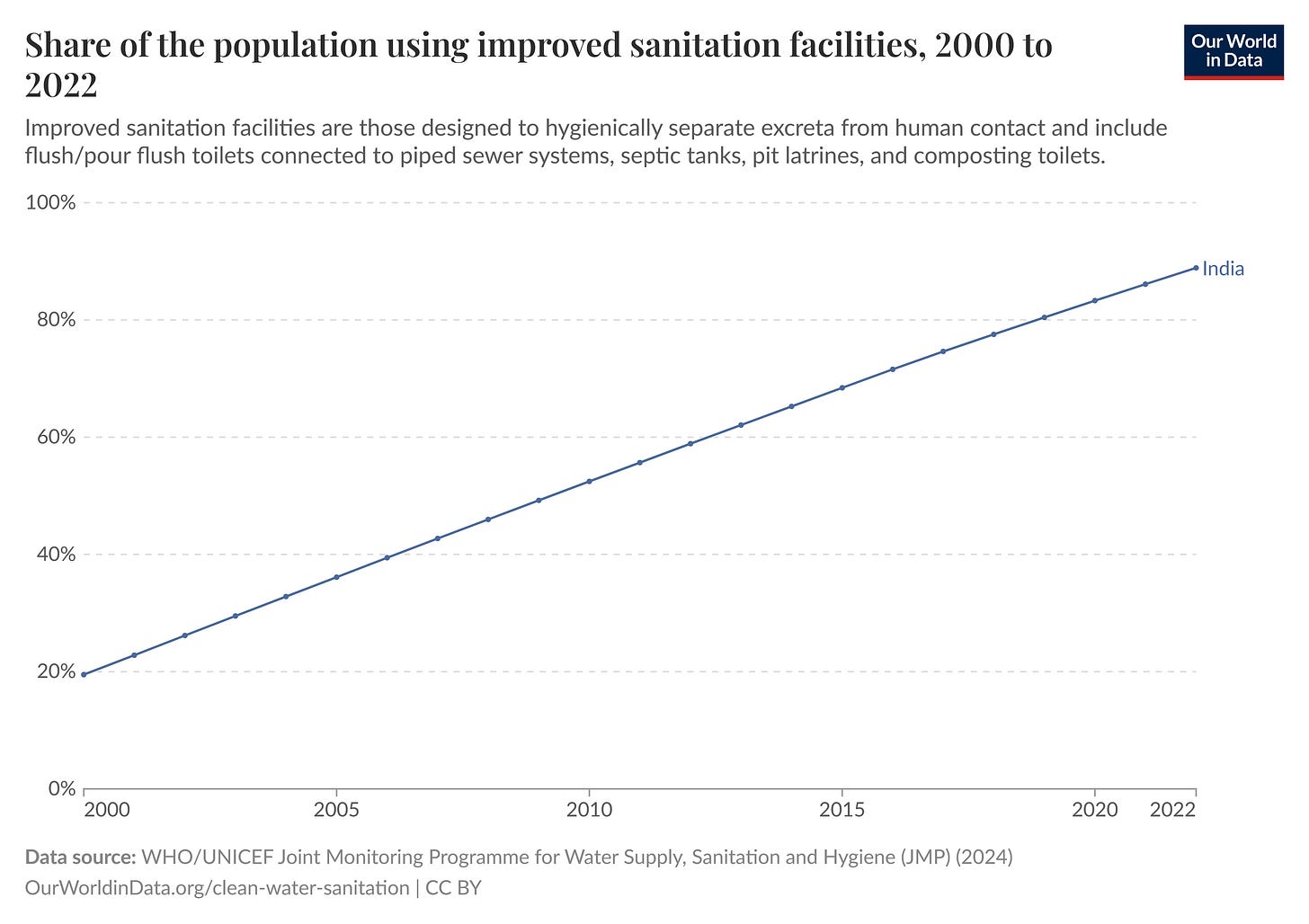

And yet, we are clearly seeing huge increases in water and sanitation access, especially in places like South Asia.

I think there is, in some areas, there is more progress. India, under Modi, has taken SDG 6 [the UN Sustainable Development Goal of “clean water and sanitation for all”] more seriously than a lot of other national governments.

What's happening under the hood? There's actually a lot. We've been advising groups like UNICEF and many other water sanitation groups for about the last six years or so. A lot of it is really trying to reframe how they work. In most cases, these are organizations that treat water access as kind of a hyper-localized problem. NGOs or UN organizations or intergovernmental groups, they go, they drill a borehole, and then they go away. And there's no thought about the kind of long-term management, maintenance operations. There was very little planning. Sometimes there actually are even kind of strange negative impacts that come from it.

We could probably even go in and say that some of these projects have effectively killed people. Because when they site them, they site them where there are a bunch of very poor people. Where do you find a lot of very poor people on land that was inexpensive for them to have access to? What does that land look like? It's probably in a floodplain.

So the argument would be that building water infrastructure, that enables more people to live in that floodplain?

That's right, exactly. Keeping them there. And also not building water facilities that will be able to survive a significant flood. What happens when you have a flood in an area where there's an unprepared borehole? Bacteria get into the well. They get into the groundwater. Suddenly, you change teams.

The well changes from being a conduit from clean water up to pollutants down. The fact that there's a borehole in the floodplain then becomes actually harmful for the groundwater.

Exactly. It will then make people sick. This is something that they figured out in London in 1830.

So what's your advice? We obviously need to be constantly innovating to make sure that aid and development efforts do the most good possible and don’t have unintended negative consequences. And we’re also discussing this against a background of anti-aid politics, and some of that has led to horrible stuff like the insanely cruel and completely indiscriminate attacks on U.S. foreign aid by DOGE that have already murdered so many innocent people.

What is the course that is maximally helpful? I've seen some interesting stuff. There’s market-based models like microlending, like the U.S. Development Finance Corporation, completely bottom-up remittances, more effectiveness-focused charities like GiveWell and GiveDirectly. What do you think is the best way to help with water resilience and water access in developing countries?

Well, I'll say water access is different than water resilience.

For us, working with these types of groups, they're called WASH groups, Water and Sanitation and Hygiene, that's what that acronym stands for. We're trying to support and enable these organizations to do something better. I think in part, these are water groups that don't actually make use of water knowledge.

What do you mean by water knowledge, there?

Hydrology. Engineering. Climate science.

To their credit, when you talk to these groups, what they focus on is urgency. That if we don't get there, if it takes us three extra months to prepare a project, then there will be X many children who die because we didn't have the borehole there.

My point is, do you want the operation to be there in 5 years? Do you want it to be there in 20 years?

The very first conversation I had with a major WASH NGO was, “Given the statistics that you've given me about the failure rate of your installations, how long were you intending for them to last?” Their first response was “Forever.” I said, is 20 years close to forever? And they said, if we get here 20 years, we'd be really happy. Okay, if 20 years is your goal, then you need to be doing things a lot differently.

So what is some of the water knowledge that they need to be thinking about?

Well, water is an expression of hydrology, ecosystems, and climate. So it's also an expression of other stakeholders and users. There are people who are upstream and downstream.

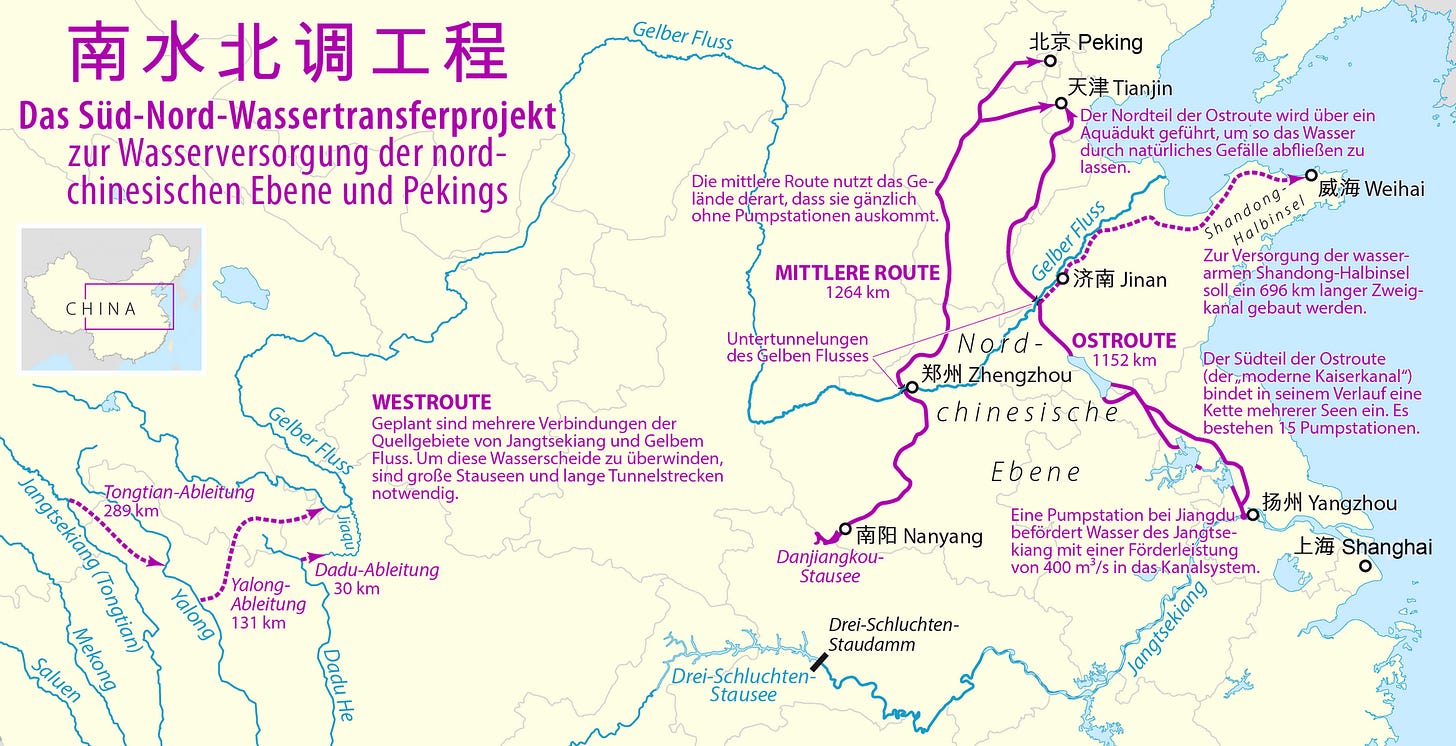

Water can also be moved. 70% of the water in Beijing actually comes from about a thousand kilometers away in the Yangtze, and it's pumped there.

They're still using, I think, the Grand Canal that was built during the Sui Dynasty in the 600s, that channels water north from the Yangtze?

That's a pittance. Starting around 2005, the Chinese government began a project called the South North Water Reallocation Project.

There's a historical tradition of large water allocation projects. I know that that's not fulfilling the needs of Beijing today.

Historically, you're absolutely right. The Grand Canal is interesting, but that's mostly for transportation, north and south. If you're interested in some of their really ancient water reallocation projects, there's one in Sichuan province that's around the Min River, a massive agricultural diversion called the Dujiangyan irrigation system. Over 2,000 years old. With the Grand Canal, they're considered the great engineering feats of ancient China. They are truly impressive in terms of how they still move water around for vast numbers, millions of people in terms of water movement.

The South-North Water Reallocation Project is literally pumping water in tunnels that you could drive a full-size vehicle down, a series of large tunnels starting from three different locations in the Yangtze and pumping that water over mountains.

The Chinese have long been aware of climate change and it's an influence on their civilization. They've gone through several interesting periods of what we would now consider minor climate shifts that they've had to respond to in significant ways.

I don't mean to pick on WASH organizations. Many groups, even large global organizations, are basically using 19th century ideas about water for 21st and 22nd century problems.

And the point is not to delay urgent action. The point is actually to make reliable, long-term investments in these communities that actually make sure that the clean water — and all of the water embedded in agriculture, energy, cities, and ecosystem — is reliable and resilient despite the weird new conditions we face.

So could you walk me through an an ideal AGWA project that is a long-term investment? How does that philosophy culminate in different approaches on the ground?

Well, a lot of AGWA work is at the level of decision-making. We're a network. We're an NGO with a strong core staff and secretariat and technical personnel, but we're also a network with around 3,000 people in it globally. Often we have organizations that reach out to us and say, “We're trying to figure out how to address climate risks, or to develop adaptation resilience strategies. How do we do that?”

We start by looking at how they make decisions now and then try to see where climate information are really important to be able to include in their decision-making and how that might offer up a new set of choices. In the case of WASH organizations, that really means that they need to be thinking about how water moves and the appropriate use of technology that matches the communities that people are working with. And making sure that you're trying to think much more holistically about about where water is, and what may be short, middle, or long-term threats to the reliability of that system.

So to go back to a borehole in Tanzania. If you want to make sure that you are not placing a borehole in a floodplain, but maybe there was some reason where you felt you were forced to, maybe that it was not really possible to help the community relocate or a non-flood exposed place would be foor, then how can you potentially, let's say, lift the borehole so that it’s shielded from extreme flood events? And not just flood events that maybe we have some historical record for, but also the big, strange floods that are still yet to come.

Resilience thinking is actually like a really new approach. Most boreholes, they require electricity. They are a pump. Where is that energy coming from? Is there a backup system? How is it managed? What are the limitations in its supply chain? Is there a way that you could convert it in a crisis to a hand pump instead of just an electrical pump?

Also, you might need to be thinking about a backup borehole itself. Maybe drilling three is better than drilling one, so you’re dispersing the risk exposure of the community.

And also trying to think maybe in a more balanced way, like how often we think about kind of the most vulnerable, the most exposed. I call that the polar bear problem. I was trained as a conservation biologist. I'd say, actually, we can't do much to help polar bears anymore. Maybe we need to think about animals that are living in the taiga, even farther south, where we have some influence and a broad set of choices that are open to us. I'd say the same thing is true about many communities, that there is a role for disaster risk reduction and disaster management and response, but probably the communities that we can help the most are the ones where there's more room, more options.

In effect, we need to be reinforcing and preparing those communities to receive folks that are coming from other places where we have fewer options, where we have less that we can do with them.

The same way that, realistically, we probably can't do a lot to make Shanghai fully climate risk-proof. That's a city with 25 or 30 million people. But the secondary cities in China, we can still do a lot with them, right? They're smaller and we need to think about long-term growth patterns. Cities last for millennia, or at least centuries. Thinking of them in a kind of narrative arc of history is really important. How can we guide their long-term development so that they are, in effect, preparing themselves for impacts that they may not actually really experience until well into the next century?

Okay, that is fascinating.

There's sort of a classic Scylla and Charybdis of development technologies, right?

On one side, the hype of jumping onto some bandwagon of something that's maybe not proven yet, not field tested, and maybe attracts donors, but isn't actually super useful on the ground. There were so many examples of that, like the PlayPump fiasco. There's many, many tales of trying to bring some technology to a region where it's just not useful.

But on the flip side, there is also a risk of locking in with outdated infrastructure that imposes serious costs. For pumps and boreholes like you're talking about, I've just been reading about how in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Philippines, for a lot of existing irrigation pumps, diesel costs have become huge, and that causes local pollution. Forget the whole emissions aspect — that's not the priority for people trying to irrigate a subsistence farm! But just the cost of constantly importing fuel is huge. And there's a non-zero chance that we'll see fossil fuel market crashes in the upcoming decades as their demand contracts. There's a stranded assets risk.

What is your take on the balance of using new and/or incumbent technologies?

It's a really good question. This is also, I'd say, a case where a little bit of knowledge is dangerous and context is really important.

One of the classic examples is in Pakistan and India for small-scale farmers. They were concerned about the diesel cost for these farmers, that their primary water source was pumping well water using these diesel pumps. About a few hundred kilos, about the size of a kind of armchair. Diesel is much more expensive in South Asia than it is in many other parts of the world. So they bought a bunch of solar-powered pumps. You know what that did? It exhausted the aquifer because it removed all of the cost from groundwater pumping.

It worked too well, essentially.

Yeah. The scale of the electricity is significant. It would be worthwhile to Google a major blackout event that seems to have been largely erased from at least Western collective memory. In the early 2010s, many farmers had switched to the electrical grid in India for their pumps, and then came the 2012 India blackouts.

Most of the electricity in India comes from hydropower, it tends to be up in the foothills of the Himalayas. This was a very dry year. A little bit into the dry season that year, the demand was so extreme and the available water for hydropower generation was so low that something like 600 million people lost electricity!

So these are not simple problems, right? I think, to me, what climate change really should make us do is step back, pause, and make sure that we understand the problem correctly. The problem is often not just a short-term issue. When we're thinking about adjusting our economy, we're talking about major infrastructure changes and also major governance changes. We're rebalancing the economic value of different sectors and assets. We can have very easily terribly unplanned and uncoordinated and indirect impacts that are catastrophic.

On one hand, I get what you're saying. On the other hand, we don't have infinite time to workshop a perfect solution. I'm a little allergic to “step back and look at the problem” stuff, just because I've seen a lot of cases where people work on something and it adds up to like three years to produce a 60 page PDF advising better ways to do things.

I know that's not what you're doing. I'm just saying, this is another Scylla and Charybdis thing, where we’ve got to find actionable intelligence to do stuff very fast in the short term that is also not acting too rashly and causing dangers.

No, I completely agree. The idea of delaying things to generate a bunch of reports also kills people. I think in many cases, what has happened in a lot of development aid is that we've tended to try to optimize for one thing, typically. Just step back a little bit. Trying to think more broadly, to think about ecosystems and people, to think about mitigation and adaptation. We have a very large set of examples about what does and doesn't work, and we need to make use of it. AGWA's work is trying to spread that information around. and make sure that people are making better use of it.

I gave a talk a couple of years ago to a group of philanthropies that fund WASH. Right now, most of them are kind of on the front lines of WASH funding given big changes in bilateral overseas development aid. And I said, if you're not careful, you will be killing people with the types of investments that you're making. Climate change is relevant in terms of the impacts and the need for adaptation and resilience to your work, and you need to be able to include it. We have successfully worked with organizations to be able to help them build those perspectives into their investment.

I'd love to hear more about this, just to concretize it. Raising the boreholes is a great example. What do other resilience measures look like on the ground? Your report mentioned technical support for work in Nepal, Brazil, Egypt, and Malawi that AGWA has been working on. I'd love to hear more about those projects in detail!

Well, so one of our most important tools has been running for about almost four years now. It's called the Water Resilience Tracker.

This takes some of our insights that we've really built up over the years. It's a program that we carry out in phases. It's also not like a bunch of people from outside of the country going and telling people what to do. It actually begins with asking deep questions.

I would actually say that, in a sense, the first phase of the work of the tracker is really a Socratic methodology. To give you an example of how that plays out in practice, in Brazil, the Brazilian governmental team that we were working with, they were leading a lot of the national work around climate planning and trying to do adaptation and resilience across most different ministries. Using our questionnaire, they went to the agriculture ministry. And the agriculture ministry had stated publicly that one of their ambitions was, to cope with declining rainfall patterns, particularly in northern and eastern Brazil, they were planning to triple the amount of irrigation investment over the next five years.

The people we were working with were taken aback. They're from a water agency that's in the development ministry, it's called ANA, and their response was, “That's really interesting, where are you planning on getting the water?!”

Literally, the agriculture ministry said, “That's not our problem.”

Wow, okay, so definite siloing, lack of coordination.

Exactly, and then treating water basically as a number rather than as a variable in an equation. They're thinking that it's just going to show up and it's going to be consistent and reliable, it's going to be the right quality, it's going to be in the right place at the right time. You can do a lot, but it will take some preparation and planning to be able to do it.

There may be areas where maybe it would be too expensive to get enough water there. Maybe they need to be abandoned from the point of view of agriculture, but that may also open up other areas where agriculture is newly viable.

It's a very similar example also from Brazil. Brazil tends to look pretty good from a clean energy perspective.

But a lot of that's hydropower.

Yeah, that's right. Lots of hydropower. Which is usually viewed as a clean energy approach. Also, most of their fuel system is from biofuels.

Well, the hydropower depends on predictable water levels, and there are lots of assumptions, quantitative assumptions, that are made in the design of hydropower facilities, reservoirs and pumps. Many of the reservoirs, pumps, the hydropower facilities in Brazil are relatively new. They're from a few decades past.

But you can look around the world, the Hoover Dam in the U.S. is a great example. It's about 90 years old. It only holds less than half of its capacity now in terms of water because of climate change. This is the largest dam in the U.S. They thought that there was going to be a lot more water than there is now. Now the water levels are so low that it's very likely that it will cease hydropower production within the next one to three years.

The Kariba Dam, it's on the Zambezi River in East Africa [between Zambia and Zimbabwe]. It's a gigantic dam. It's only a couple of years older than me, I'm 57. It's also one of the largest dams in the world. It was a World Bank project in the 60s.

During the dry season, it's now only able to generate something like 5% of its energy capacity, because the flows in this area have changed so much over the past few decades!

So what an economist would say is that these are now stranded assets. These are assets that we paid a lot of money to put them there and to run them and operate them. They were supposed to generate a lot of economic benefits and growth. We also paid some extra costs in terms of ecosystems that were damaged or communities that were displaced. And now it's like wearing an anchor around your neck and then going for a swim. They are destructive assets. They're straining and actually making the areas around them poor.

The U.S. has spent something like $1.5 billion to do some marginal adaptation work on the Hoover Dam over the last 15 years. Kariba Dam, the Chinese are trying to also do some reconstructive work on it, but they're not going to change the seasonal monsoons, right? There's still going to be serious issues with this huge dam looming over for a very small amount of energy production.

So in Brazil, our colleagues at ANA, they asked [other ministries] two questions. One is, “Have you thought about how future or maybe even current climate impacts affect the hydropower production?” And they said “No.” That was pretty shocking!

Also, they asked, “What happens if you start storing more water behind the reservoirs and the farmers downstream get upset because now there's no longer any water for them?” “I haven't thought about that.” “Do you think you should talk to the agriculture ministry about how the two of you are sharing water in the same places?” “We haven't done that.”

Biofuels, where do biofuels come from? In Brazil, they come from sugarcane. They come from irrigated sugarcane, actually. And also when the sugar cane goes through processing, it is an extremely water expensive process.

That's liquid biofuels?

That’s right. The energy ministry had not thought about how that might be changing. Or the agriculture ministry, because both of them share some management responsibilities over the biofuels system.

So these are areas where you need to see the problem in order to address the problem. It's not going to solve itself by accident. And they need to begin addressing these.

Our point is not to embarrass anybody. It's not to make them feel ashamed. It's a process that essentially every country is going through right now, to think, “How do we get ready for a drastically different climate? Can we leverage the special properties of water to leverage effective climate action?”

Brazil, I would say to their credit, they've been very, very honest with us, with other ministries, in saying “We have a serious problem here and we need to think about expanding our energy portfolio, both for fuel and for the electrical grid.” Thinking about how we don't get into the same kind of severe bottlenecks that, say, India did, with blackouts for 600 million people.

So, I think these are tractable problems. but they won't be tractable unless people start working on them. That's a big part of what the tracker is meant to be able to do.

There is a view, I think, by a lot of people that climate risk is something that you can measure like with a barometer or a thermometer, that you can say “our climate risk is 6.7.” I would say climate adaptation and resilience, fundamentally, it's about negotiating trade-offs. That has to be made by communities. It has to be made by countries.

Brazil may say, “We need to invest in some other types of energy production.”

They are already importing tons and tons of solar and batteries. I've been writing about that.

That's right. And that seems like a very sound approach. And hopefully not thermal systems [generating heat to boil water to turn a turbine for power, as with fossil fuels or most fission reactors]. There have been some issues there

Coal and nuclear plants have been shut down, at least temporarily, due to water issues. The water impacts of climate change can bring intermittency, the feared bugbear of renewables, to fossil fuel stations!

Absolutely. It can happen in interesting, complex ways. In France, for instance, the last water user that has a claim in an extreme event are the nuclear power plants. I think something like 80% of France's power comes from nuclear. And of course, these are water-cooled systems. Increasingly they will probably have to think about other water-independent systems because their energy grid is actually expanding quite a bit. Around 2013, there was a severe heat wave in France. Like 13,000 people died over the matter of a couple of days because of severe heat, Mostly elderly folks in their own home, or in retirement facilities and healthcare facilities that didn't have air conditioning.

They had heat almost as extreme this year, but they had very few deaths. The reason is that they were able to think very carefully about air conditioning as a form of localized climate adaptation.

But it has an impact on the electrical grid. They need to have more energy for those crisis situations. And it probably needs to be independent of water systems, right? You can decide that a field of wheat can die because you don't have enough water for it. But what do you do with a vineyard where the vines are 150 years old?

Yeah, it's difficult. You’ve got to do the adaptation, got to do the air conditioning, got to make the trade-offs.

Exactly. I'd say something that's a very widespread misunderstanding about climate change is that a lot of the impacts are not easy to predict, and they may be really perverse. People tend to focus on, “oh, we're just going to have less water,” or “we're going to have more intense floods,” or “more extreme heat.” I would say it tends to be a more complicated story. The way that you prepare for a portfolio of types of impacts is a complicating factor, but it's a necessary element in how you think about issues.

The electrical grid in Texas, just a couple of years ago in 2021, there were huge outages. Some estimates suggest that the damage that occurred over this period represent something like more than 2000 USD per resident in Texas! The cooling ponds for all the thermal facilities, they froze. That was actually the biggest challenge.

The natural gas facilities were offline due to water intermittency!

That's right, exactly. And it wasn't because there wasn't water there. There was water. It just happened to be frozen. And they had never designed these facilities to be able to operate under extended low temperature conditions.

Because it was in Texas, which normally doesn’t get that cold, the polar vortex has gotten deranged lately, and it does random cold snaps.

Exactly, exactly. This is the kind of complexity that we have to be facing. California, just a couple of years ago, they had to take three natural gas facilities in mothball status and reactivate them because there wasn't enough water in their hydropower reservoirs for the state's energy needs. That's a trade-off, right?

There's a great writer, Doug Lewin, who does a Texas Energy and Power newsletter.

Price spikes have become less common in Texas lately because they've been the U.S. state building the most renewable energy. That's been an adaptation measure in addition to a mitigation measure that's helped stabilize the grid.

Exactly. Yeah. That's a great example of a win-win, right? We definitely need to maximize for those.

One heuristic I'm trying to go for is because the world is complex and there are often unforeseen outcomes, you should try to get win-wins. When people bite the bullet and they're like, “We have to accept this bad thing to avoid some other bad thing,” often it turns out actually you could have done it better. We should try to go for solutions that are as multidimensionally helpful as possible.

I completely agree. The other part I would add is because the water cycle is so sensitive to the climate cycle and it's also really hard to predict, it's also essential to how we think about adaptation and resilience strategically, respecting the special issues of managing water in a dynamic climate.

What that often means is we need to think about agility and flexibility in our systems. We need to be able to think about how we might be able to plan and prepare for a more complicated future. We do need to consider a longer-term plan. What happens if this solution doesn't work or starts to taper off in its efficacy? What's the next step in that? And how do we prepare along those lines?

I think that also means that we need to move up a little bit in scale. It was stated really well to me by someone from the Asian Development Bank a few years ago. She was on an island in the Pacific where they had multiple, four, five climate adaptation projects that were going on simultaneously, in this small island state in the Central Pacific. I won’t give the name. The country's taking out millions in loans for these projects. She's looking in the harbor at projects for ships, she's looking at efforts to give the water utility a little bit longer lifetime as well. And then she's looking at what their own statistics show in terms of flooding for the capital. By their own estimate, the capital would be underwater soon. And it's a big deal to make a new capital. You can ask the Indonesians. It's going to take 10, 15 years, easy.

So what does a resilient outcome look like? In the case of this country, they probably needed to say, “Realistically, in 2050 or 2100, we probably need to have a capital that is not the lowest relative to sea level on the planet. We probably need to have one that is 10 meters above sea level. How do we get there? And if we're going to think about the economic viability of shipping for our economy, then how do we make sure that we build something that maybe can be developed as shipping facilities that can be built in stages over time?”

It gives us options. Maybe we don't have to spend all the money at once, but we can begin and prepare.

I think nature-based solutions are actually one of the really positive stories here. Nature-based solutions often have a lot of flexibility that's built into them. Using them right, ecosystems tend to want to adapt and adjust on their own. They tend to naturally reorganize themselves with climate adaptation and climate shifts. That's what they've done for over a billion years. We can make use of that!

An example also from the Pacific. Fiji was preparing to build on one island a new seawall. It was going to be built out of hard imported materials, very expensive materials and concrete rebar. During the pandemic, they arranged all the financing for it. They actually couldn't get that material shipped to them. It was being diverted during the pandemic to other countries.

They said, well, we still have coastal erosion problems. Let's actually go with native materials, local materials. It may fail more quickly, but we can fix it more quickly, too. And it was a lot cheaper and ultimately more flexible for the communities.

What else would you like to share?

I think a big one is that resilience is a new concept. I really think of it as a concept that is not just an engineering principle, it should be a kind of deep cultural concept. It's something that we almost need to take in at the spiritual level. We have organized ourselves now for centuries, if not millennia, in a way that assumes that we really know exactly what the future is going to look like. We've managed ourselves, our lives, in a way that has this kind of confidence. And the Greeks had a word for that kind of confidence. It's hubris.

Resilience, to me, is about losing our hubris about what the future is going to look like. And in that sense, resilience is not just about climate change. Resilience is about the geopolitical and geoeconomic turmoil that we're in right now, too. To me, the positive message about resilience is that it's something that we can bring into our lives as individuals. We can begin to think about how it plays at the level of our households, of our community, of our state, of our country, and our globe. And those are very positive messages. They're also really different messages than the way that people talk about climate change.

It’ll probably take us a century to just fully absorb the concept of resilience.

A lot of groups, a lot of indigenous groups, our ancestors in medieval Europe or in ancient China, in ancient Peru, I think they understood something about this concept of resilience, in a way, that we need to be able to relearn.

We actually messed up a lot and we had to figure it out before we started to get it right. We need to think with that kind of humility about the future and its increasing complexity, in a way that doesn't generate despair, but I think gives us a kind of practical optimism.

Yeah! Like the difference between hoping that someone will give you a boat and thinking you can build a boat.

Hydrology is important. There was a study that just came out last week that showed that about 2,800 years ago in ancient Judea they created a large dam just on the edge of Jerusalem because of essentially microclimatic changes in hydrology. These are not new things. We can respond to them.

And we need to think about water as a system, and a system that's embedded in ecosystems, that's embedded in the climate. It's evolving really quickly right now, and it's going to keep evolving.

Thank you for sharing this!

Take care.

Thank you so much, John.

Nice post on a still important topic thanks. Whish there had been more figures on the actual engineering and costs challenges faced by people that actually build the stuff, or at least know the details of how it's built (piping options, installation methods and challenges, logistics). Anecdotes and "holistic approach" type of fluff can only take you so far in understanding the real problems and thinking up better solutions. Still, thanks to both, was good stuff.

Anyone interested in AGWA, our organization, can learn more at Http://alliance4water.org. I also run a substack called Deep Resilience: https://deepresilience.substack.com/. I hope this is the start of a conversation more broadly with the readers of The Weekly Anthropocene!