Interview: Dr. Katharine Hayhoe, Climate Scientist

A conversation with one of the world's leading atmospheric scientists and climate communicators

Dr. Katharine Hayhoe is a world-renowned atmospheric scientist and climate communicator whose work has contributed to over 125 peer-reviewed publications, including four U.S. National Climate Assessments. She was one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in 2014. Dr. Hayhoe is a Distinguished Professor at Texas Tech University and in 2021 became Chief Scientist at The Nature Conservancy.

writes on Substack.In the interview below, this writer’s questions and comments are in bold, Dr. Hayhoe’s words are in regular text (occasionally italicized for emphasis), and extra clarification (links, etc) added after the interview are in bold italics or footnotes.

Can you discuss the current state of where we are on climate change? According to my understanding, we've probably missed our shot at staying under 1.5C of warming, but on the plus side we have clearly averted the high-emissions trajectory leading to 4 or 5C of warming by 2100.

How has our trajectory changed since 2010?

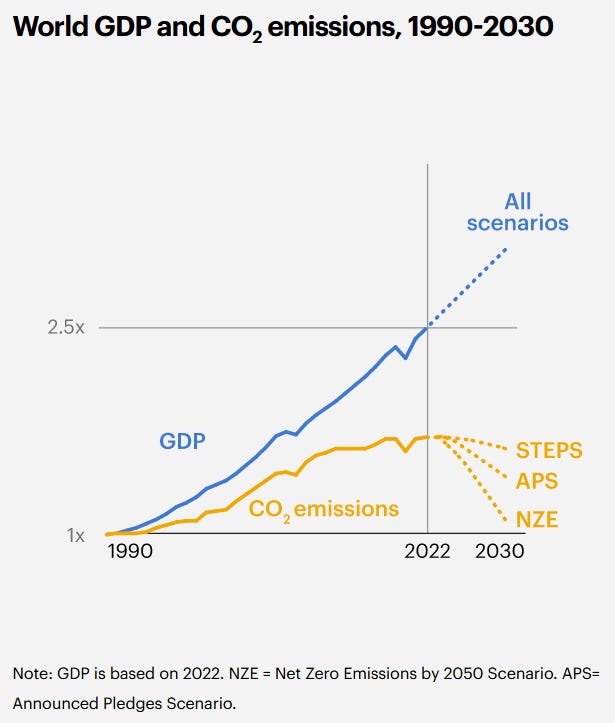

This is something people don't realize. People think nothing has changed. But before the Paris Agreement, which was a global treaty where all the countries in the world agreed to take climate action, before the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015, less than 10 years ago, the world was headed to four to five degrees Celsius by the end of the century.

4 to 5 degrees Celsius (°C) is 7 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit (°F).

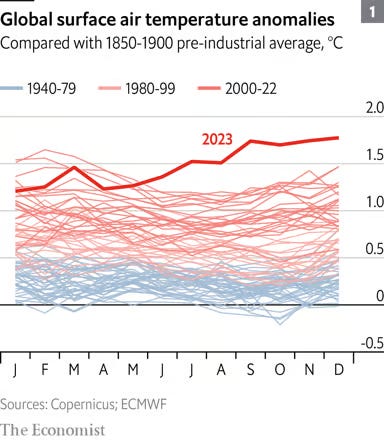

So why is this a big deal? Well, the average temperature of the planet over the history of human civilization has been as stable as the temperature of the human body.

So over the course of a day, your body temperature goes up and down by a few tenths of a degree, and that's normal. Over the course of human civilization the average temperature of the planet has gone up and down by a few tenths of a degree, and that's normal.

We're above 2°F now. If your body temperature goes up by 2°F you're running a fever. So our planet is currently running a 2°F fever and it feels achy. It wants some Tylenol and it's calling the doctor. Imagine if your body is running a seven to nine degree temperature fever. You are in the hospital. It is a life threatening illness.

So 10 years ago, we were heading for a “life threatening illness” of seven to nine degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century. Today, thanks to policies that have already been enacted—not promised, enacted!—we have almost halved that.

“Ten years ago, the world was on a pathway to warm by up to 5C (that’s 9F) by the end of the century, according to the analysis I led for the last U.S. National Climate Assessment. Today, thanks to policies enacted since the Paris Agreement was signed…current policies will limit warming to 2.7C (5F) and this number could fall even further with more aggressive climate action.”

-Dr. Katharine Hayhoe (on her Substack, not in this interview).

Halved it! That's phenomenal news.

I call this the “victory that deals not speak its name,” because in the current information environment, everyone is incentivized to ignore that.

The right is incentivized to ignore it because they don’t want to acknowledge that there's an issue, and the left is incentivized to ignore it because any organization working on an issue in a social media environment leans towards catastrophism to try to scare people into donating more.

So, the threat of climate change in terms of warming expected by 2100 has been cut now in half. You, one of the premier climate scientists in the world, are telling me this right now.

Yes. And this is what I do. I study future projections.

That is such an insightful comment. You have hit the nail on the head. The people who don't want climate action don't want us to know it's already happening. It's already succeeding.

But the growing problem, the problem that is growing bigger every week, is the fact that the people who are very worried about climate change are still convinced that the only thing that persuades people to act is doom and gloom. A study just came out last week that showed that doom and gloom gets the most shares and clicks on social media, but it is the absolute worst at getting people to actually take action and support climate policy.

So what I propose personally is, I propose we need 50/50 [positive/negative communication on climate change]. And what we need [to focus on in climate communications] is not Antarctic ice sheets, ocean circulation, and polar bears. That's not even in my 50/50, because unless you live in Antarctica or you are a polar bear, you don't understand why that matters to you. What we need is 50% about what's happening where I live that affects people I care about, places I care about, things I care about. What's happening in Maine? What's happening in Texas? What's happening to places I go or things I love, like chocolate and coffee and bananas, as well as my kids or my family or the things I enjoy doing? That's the first half, the risk of inaction.

The second half we have to understand is the rewards of action. What's already happening? How much money are people saving? How much carbon are we already reducing? How much better are people's lives becoming?

Here’s an example. Whenever I get an Uber, I always try to get an electric Uber. The last electric Uber I got was a Tesla driven by an older man named Kurt. It was a 45 minute drive, and that entire drive, all 45 minutes, Kurt told me how much he loved his car, how fast it was, how it accelerated, how it had a beta training program that he could put input into, how it had these cameras. He never mentioned climate, never mentioned carbon emissions, never mentioned that it was electric, just how much he loved it. He was the best Tesla ambassador in the world. Didn't care about climate change, just talked about how amazing the solutions were. We need a lot more of that.

“Didn't care about climate change, just talked about how amazing the solutions were. We need a lot more of that.”

-Dr. Katharine Hayhoe

Absolutely. Renewable energy is a good deal on its own terms! Decentralized energy, resistance to the price shocks of oil markets, lower air pollution deaths, lack of PM 2.5 emissions. There are so many other things that it does better than fossil fuels, even if you totally ignore climate change.

And this really ties into one of my big questions, which is, all of a sudden the corporate world seems to have really switched to renewable energy in a big way. To an extent that sometimes more business-friendly states are building more renewable energy even if they're also climate-denying states.

I'm sure you saw last year, Texas overtook California in total installed grid-scale solar capacity. Which just blows my mind! But more solar is being built in Texas because it's easier to build stuff there. That's because of, like you said, people like Kurt who just like the energy or the car or whatever and don't care about climate change. And that's a good thing, obviously. We're getting the solar built. But that has just been a really shocking trend that I've noticed. So what are your thoughts on that?

Oh, you're totally right. They just built the biggest utility scale solar in the US so far, just outside of Dallas, and it was specifically to attract companies who wanted renewable energy.

The last couple of weekends in Texas, we've gotten up to 85% wind and solar energy on the grid. In Texas! Do I care why? No! The climate doesn't care why. Do they have to pass some type of climate purity test before we're allowed to use wind and solar? No! If somebody wants to use it because it's cheaper, if somebody else wants to use it because they can make money, if somebody else wants to use it because it doesn't produce air pollution—which kills millions of people a year by the way!—and if somebody else wants to use it because of climate change, bring it on. We're all in this together.

“The last couple of weekends in Texas, we've gotten up to 85% wind and solar energy on the grid. In Texas!

Do I care why? No! The climate doesn't care why.”

-Dr. Katharine Hayhoe

100%. I absolutely agree with this.

And also, given that we're on the same page on this, I feel like the climate movement has evolved this sort of radical fringe that is really, at this point, almost as disconnected from the data as the climate denial is. If you look at some of the claims being made by Extinction Rebellion, they’re just not based in reality.

First of all, I will say this, that as a scientist, I know that we are underestimating the impacts on people because we've never seen changes happen this fast.

Our projections of global temperature from 50 years ago are tracking exactly where we are today, So in terms of what's happening to the planet, we have had a very good handle on that for a very long time because it's basic physics. We also know that we are underestimating the frequency and the intensity of extremes, because they're so far at the tail of the distribution we just don't have enough data to accurately model them. So we know that we're going to be seeing even worse climate events.

So with that caveat, just to be clear, I would say at the same time I hear a lot of people making claims that are not true, like that climate change will lead to the extinction of the entire human race. [Which, to be clear, is not true]. Or even worse, saying there's nothing we can do, it's over.

About once a week, I actually run into somebody on social media who's out there just saying, “There's nothing we can do.” And I say, “Look, I understand your anxiety, I understand your despair. I'm a climate scientist, I live in this. But if you're on social media to tell everybody there's nothing we can do, GET OUT OF THE WAY! Get off social media, go to the local rescue shelter, adopt a pet, take them for walks outside, spend time in nature. Do things with people you love. Address your mental health issues. But don't get in the way of the rest of us who are fighting for a better future. Because I know without a shadow of a doubt that every action matters. Every choice matters. Our future is in our hands. Don’t give up now after we've actually started to finally make some progress!”

So that is definitely something I see and is something that I fight against. And you're right. There's a small but growing number of people who are so far at the opposite end of the spectrum from denialists that they're almost wrapping around to the same message for a completely different reason.

Exactly. Yes. The same message. Do nothing, with a big heaping dose of utter despair. It adds up to the same thing. It has the same function of actually stopping people from doing useful things.

In one study, they found that only eight percent of Americans are “activated,” taking some action related to climate change. They asked people who were alarmed but not activated why they weren't activated, and the number one answer they got was not “Because I don't think we can fix it,” but “Because nobody asked and they didn't know what to do.”

Okay, fair enough. It's a lot of space for us to make a difference!

Related to that, I feel like maybe the second biggest story in climate, after the global exponential growth of renewable energy having cut expected warming in half by 2100, the Inflation Reduction Act, which if you're an American taxpayer provides this gigantic cornucopia of stuff to do and a huge amount of federal money to do it with. I feel it has just been insanely woefully undercovered in the media. We got a green New Deal and it sometimes seems like nobody cares!

Well, you are totally right. It is the biggest piece of climate legislation the US has ever seen. And when I'm in other countries, you know, I'm from Canada and I work with a lot of people in Europe, everybody there is actually talking about, how are we going to compete? This thing is just so big, so ambitious, so many carrots to kickstart manufacturing and bring down the price of new technology. People in other countries are asking, how are we going to compete with this from an economic perspective?

Why aren't we realizing it? Well, I think there's a couple of reasons. So first of all, number one, obviously the title was very smart because who doesn't want to reduce inflation, right? But the title was also very wonky, because it wasn't called The Biggest Climate Bill Ever. It was called the Inflation Reduction Act.

If it had been called The Biggest Climate Bill Ever, I think people would have understood a bit more about what it was doing, but it would have had less broad appeal.

If you're a a manufacturing entity in a conservative state, you don't want “Brought to you by The Biggest Climate Bill Ever” on your factory. You want “Brought to you by the Inflation Reduction Act” on your factory. So I think the naming was clever, but it prevented a lot of people from understanding it.

Also policy is very wonky, and just like science it requires good communication. You can have the best science in the world, you can have the best policy in the world, but if you don't communicate it effectively nobody's going to know. I don't think the IRA was communicated as effectively as it could be.

Organizations like Rewiring America and the Washington Post have done great handbooks where you can put in where you live and how big your house is and how much money you have, and they'll tell you what to do to get your rebates. But man, it's hard to do! I'm a scientist and I have problems figuring that out.

George Lakoff is a cognitive linguist, and a number of years ago he wrote a book called Don't Think About an Elephant. He says that some people think that the truth is not self-evident, that we have to communicate why something is good or why this is true. And some people think the truth is self-evident, we just put the science out there, put the policy out there, and everybody will be like “Oh, of course, okay.”

No! We have to communicate.

There's some really interesting articles analyzing this from a communication perspective. The current administration the U.S. has under-communicated the benefits of this policy.

That reminds me of how some corporations now, instead of greenwashing, they're doing what's called “greenhushing,” which under one of its definitions is taking climate action but not talking about it, because the conservatives attack them for it.

We’re in this weird scenario where huge amounts of work is being done and it's not getting much attention. I mean, that's much better than the reverse! But it’s weird.

And it's not good, because then nobody thinks anybody's doing anything. Studies show that everybody underestimates what everybody else is doing.

Part of the hushing is happening because of conservative pressure, for sure, but part of it is because of this really strong and destructive purity culture in climate activism and environmentalism, where it's like, if you're not obeying my Green Ten Commandments you are a heretic and I will metaphorically burn you at the social media stake.

Absolutely. Kim Stanley Robinson was just saying that when I interviewed him the other week. Purity is awful, straight up, as a concept. It has almost no value in any social or scientific context whatsoever. The world is always impure on whatever axis you choose to define.

Yeah, it is. Purity culture is a works-based system of righteousness for people to temporarily feel better about themselves by putting others down.

“Purity culture is a works-based system of righteousness for people to temporarily feel better about themselves by putting others down.”

-Dr. Katharine Hayhoe

Now, I'm not talking about condemning the oil and gas companies who made record profits last year and used it to slash their their climate ambitions, I'm not talking about them. I'm talking about everybody else who's doing the best they can at this time and could always do better.

It's always glass half empty. We never look at the glass as half full.

That's what my newsletter is trying to do. That's why I write this stuff.

People have this tendency to try to round things off to either really good or really bad. It's really hard to convey that things have moved from closer to the bad end of the spectrum to closer to the good end of the spectrum while still remaining neither fully good nor fully bad. But that is in fact what's happened with our climate warming risk for the end of the century.

It is this real thing that is changing the whole world that we need to smartly adapt to, but it’s an ongoing condition that we need to deal with, it's not a looming apocalypse. If there was some bright line where it says, now we are in the climate changed Earth, it happened a long time ago.

I don't know why this is, maybe it's the legacy of Christian eschatology in the culture or something, but people try to treat climate change like there's some hard stop somewhere after which everything is Doomed, and there isn't. Every tenth of a degree matter. Every year we still have to keep living on this planet and dealing with it.

You know what I'm saying? There's sort of an attempt to graft a terminus onto the climate change narrative where there isn't one.

I think it's more a case of human psychology. Because we work with goals and deadlines, we aren't comfortable with things being open-ended. I think the eschatology plays into it, and it certainly does on the other side as well. There's a strong connection between that and climate denial.

But I think it's more a case of as humans, we feel more comfortable with limits. And we don't feel comfortable with climate change. So when we put limits on the issue, it's like a security blanket.

Even disaster can sort of be a security blanket, because then you don't have to think about actually having to build stuff or deal with problems. It's just, “oh it's the cleansing disaster and everything's doomed” and then you don't have to think about what happens the next day.

I'm not expressing it well, but it’s a lot easier to say “We're all doomed,” than to say “Okay the remaining sectors of our economy that need substantial decarbonization by 2050 are the following, and here are the relevant policy levers.” One of those requires more cognitive effort than the other.

Yes. Psychologists have told us there's comfort in doom. There's comfort in giving up and stopping fighting. Fighting is hard, it's discouraging and depressing. Just giving up makes it easier.

But I want to just go back a second. For us, living middle class lives in a wealthy country, it's not an existential crisis.

The Existential Threat to Human Wellbeing is already here, but it's affecting the people who are the poorest and most vulnerable and have done the least to cause the problem.

For me, that is a huge motivator for why I fight. Because often they can't be fighting for climate action, because they are literally trying to survive until tomorrow and ensure their family and their children survive. That's a lot of what drives me, is recognizing that for some people it's already there and they can't do anything about it.

Yeah. I've written a lot about this interplay of climate and development. Because the immediate, proximate solution is to lift these people out of poverty, right? The immediate thing that will kill people is stuff like not having an air conditioner when there's an extreme heat wave, or not having a safe place to go to in case of a flood.

Development can help so much with climate change resilience. Like, when the Bhola cyclone struck Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) in 1970, at least 300,000 people died. And Bhola was a weaker storm compared to many cyclones in the warmer world of today, it was Category 4-equivalent. When a similar Category 5 cyclone hit Bangladesh in 1991, about 138,000 people died. When Cyclone Amphan (also Category 5) hit Bangladesh in 2020, only 128 people were killed.

People assume that a change in climate means that by definition, more people will die. But I'm trying to show that, you know, it means it's more dangerous, but you can have a better world, even in the face of a changing climate. You can fight poverty, and you can win. Even deaths from natural disasters have been decreasing in recent decades as the world grows richer.

So what are your thoughts on that?

Well, what this reminds me of is a figure that I've built a whole class on. And it's a very simple figure of three lobes. The whole figure represents a disaster.

How does disaster happen? What makes a disaster?

The first lobe is the hazard. The hurricane, the drought, the heatwave, the wildfire.

But then the second lobe is exposure. If the hurricane never comes ashore, then nobody's exposed. So how many people, how much infrastructure, is exposed?

The climate and weather disasters are getting stronger and more frequent in a warmer world. Hazard is going up. Exposure is going up too, because we have more people and more valuable infrastructure today than we did 50 or 100 years ago.

But the third lobe of that is the one you're talking about. It's vulnerability. We can still bring down vulnerability even if hazard and exposure go up.

“We can still bring down vulnerability even if hazard and exposure go up.”

-Dr. Katharine Hayhoe

Exactly!

We can bring down vulnerability! And one of the biggest ways we can do that is through investing in nature. Coastal wetlands protect us from storm surges. Coastal mangroves can reduce the storm surge before it hits the people, the town, the infrastructure. Greening low-income neighborhoods in urban environments can bring down the temperature during heatwaves by more than 10 degrees Fahrenheit, as well as cleaning up the air, providing a place for water to go when it floods, and allowing people to spend time outside in nature.

Yeah!

We also need to cut our carbon pollution, obviously. We need to invest in nature and technology to take our carbon out of the atmosphere and put it back in the ecosystems and soils where we want it. And we also have to help people adapt.

Here’s a good analogy. Think of the atmosphere as a swimming pool. The level of water in the swimming pool is the level of heat trapping gases in the atmosphere. At the beginning of the industrial revolution, we stuck a giant hose in the swimming pool, and we turned it up every year. First year of the pandemic we turned it down seven percent, and then we turned it right back up again. That's our heat trapping gas emissions.

So we have to turn off the hose. We have to make the drain bigger, that's investing in nature to take our carbon out of the atmosphere. And we have to learn how to swim because our toes don't touch the bottom anymore. That's adaptation and resilience. Those are the three things we have to do to tackle climate change.

Absolutely. Reducing emissions, investing in nature, and adaptation and resilience.

You have clearly put a lot of thought into really eminently graspable analogies for this. I have tried to explain or talk about some of the same things sometimes, and it was not in nearly such eloquent terms.

What is the one thing I didn't ask that you really want to share with readers?

Sure. The number one question that I am asked these days is, “What can I do to make a difference on climate change?”

And my answer has nothing to do with light bulbs, eating more plants, taking public transportation, or your carbon footprint. The number one thing we can do is to use our voices to change the system.

The system is made up of people. And why do changes happen in a business, an organization, a city, a school? It happens because one person talked about how an issue was going to affect them. And then they said, “Here's something that they're doing over there, maybe we should try it too.”

We have the power to catalyze change. Wherever we are, wherever we live, no matter how old or young we are, we all have the ability to use our voice to call for change. That is the number one thing that we can do.

Thank you so much. You are amazing.

Thank you, thank you, Katharine Hayhoe and Sam Matey for this conversation. I love the hope and how it's woven with the truth of our situation in everything Katharine shares here. I've become instantly a fan of both of you!

🙏🏼!!!!