Building a Future for Wildlife in the Anthropocene: 2019 Madagascar Diaries #6

Republishing my blog posts from my time as a volunteer research assistant in Kianjavato, Madagascar, in mid-2019

Background: from late July through mid-October 2019, I worked as a volunteer research assistant for the Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership (MBP), based out of the Kianjavato Ahmanson Field Station (KAFS). KAFS is located near the village of Kianjavato, in the eastern rainforests of Madagascar. During this time, I worked to assist MBP’s studies of the critically endangered greater bamboo lemur (Prolemur simus), as well as teaching English classes and later assisting the community reforestation program.

I wrote a series of “from the field” blog posts describing my life and work there as it happened, from a first-person “you are there” perspective. I’m now republishing excerpts from these on Substack!

This blog is delayed somewhat, leaving off on September 27th, as for the last few days Internet connection at KAFS was slow to nonexistent. Here follows a recount of my visit to the amazing Anja Community Reserve, and my last workweek with MBP’s amazing Reforestation team at the Kianjavato Ahmanson Field Station! Thanks for reading!

Anja Community Reserve: A Model for the Anthropocene

After the joy that our earlier weekend visit to Ranomafana had brought us, myself and my four fellow volunteers had agreed that we would, in our free time, visit as much of Madagascar as possible. On Saturday, September 21st, we were honored to visit one of the most amazing conservation success stories in Madagascar-the Anja Community Reserve, famous as one of the best sites in the world to see wild ring-tailed lemurs. Fredo had very kindly arranged for our driver to take us to a rendezvous with Mamy Samuelson, an excellent local guide (and, as we learned later, a man with a deep connection to Anja and its history). We met him, and two assisting animal spotters, on the side of the highway at Anja, about 13 kilometers south of the district capital of Ambalavao, at a spot with a beautiful view of two of Anja’s iconic “Three Sisters” mountains. (It was also, incidentally, the furthest south I’d ever been, as Anja is considerably to the south and west of Kianjavato). The terrain as we drove in had already made in clear that this was a completely different geological and ecological area than both Ranomafana and Kianjavato. Those had both been part of Madagascar’s eastern rainforest biome, with rolling hills and rounded mountains covered in green, lush vegetation-or, depressingly often, agricultural land and deforested, red, eroding hillsides. Anja was on was the central plateau, and here the massifs dominated the scene: huge rock faces, looking perfectly sheer from the road, on all sides of us, streaked with different colors indicating ancient differences in sedimentary rock layers. It reminded me of the Sierra Nevada mountains of California: a landscape more like the American West than the Kianjavato rainforest. There were cultural differences too: the Ranomafana and Kianjavato areas were home to the Tanala people, one of Madagascar’s eighteen recognized tribes, and most of the houses were built of bamboo and wood. Anja was smack-dab in the homeland of the Betsileo tribe, and most of the houses were built of red brick.

We hiked up towards the reserve, through a mosaic of rice paddies and cattle grazing areas. In a little bush by the side of the trail, we saw our first example of Anja’s amazing wildlife: a male and female Phymateus saxosus, gaudy grasshoppers. They looked like ordinary grasshoppers as designed by a ten-year-old into heavy metal: gigantic by grasshopper standards, a patchwork of Crayola-bright green, red, yellow, and black, with armor-like spikes protruding from unexpected locations and bloodred wings hidden under their wing covers. We swarmed that bush to take pictures of these incredible invertebrates, then proceeded on our way towards the forest.

As we neared the boundary of the reserve, a lovely scent filled the air, emanating from a thick grove of beautiful pale-pink flowering trees. Mamy said it was “Indian lilac” (Melia azedarach) also known as chinaberry, and that the ring-tailed lemurs loved to eat the fruit. I mentally noted it as an example of another introduced species benefiting local lemurs. We skirted the edge of the lilac forest, as Mamy told us about how the Anja association used the money from tourists’ entrance fees to benefit the local community. So far, ecotourism at Anja had paid for the building of a school that taught over 200 local kids, and ongoing teachers’ salaries, half of the healthcare costs of all local citizens on an ongoing basis (a better social safety net than many Americans get!), and the construction of an open-access community fish farm that provided much-needed protein for the local citizens. We soon came into view of that very fish farm, a broad, shallow lake thronged with people netting their dinner, and I nearly laughed aloud at the sight of a sack filled with the day’s catch lying on the ground. The mouth of the sack was open, and it was filled with tilapia and crayfish-exactly what was cultivated in the USM Aquaponics Lab back home in Gorham, Maine. We’d chosen them because they were fast-growing, high-protein species with wide temperature and acidity tolerances and un-picky dietary requirements. In hindsight, it wasn’t particularly surprising that those characteristics held true the world over, but in the moment, it was an unexpected and serendipitous resonance with home.

A bare five minutes after first seeing the fish farm, we saw our first group of ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta), licking rocks and earth for minerals in a little open patch of grass between the lakeshore and the chinaberry forest (pictured). We all froze, gasped in awe, and whipped out our cameras and phones, but Mamy and the animal spotters urged us on, closer and closer until we were barely ten feet from the lemurs. We snapped pictures madly, sure that they would scamper away as soon as they realized our presence, but instead they strolled about as if we were no concern at all. Some even came closer! It was the closest I had ever been to a wild lemur, and certainly the closest I had seen wild lemurs to such a large concentration of humans-children were walking by regularly on the lakeshore twenty feet away! It was absolutely incredible to see such magnificent, iconic creatures at such privileged proximity. Making matters even more interesting, September was the birthing season for ring-tailed lemurs (as it is for many other lemurs), and many of the females we saw had babies clinging to their bellies. One even had twins, with one baby on her belly and one on her back. We sat there on the grassy verge for a while, taking pictures, selfies, and simply witnessing the behavior of these breathtakingly beautiful animals. At one point, we were even privileged to witness a small “stink fight,” where the males smear their tails with scent from the scent glands on their wrists and ritually shake them at each other. It was amazing. I had thought no lemur species could exceed the habituation to humans of the greater bamboo lemurs of Sangasanga, who peacefully fed on bamboo when observers were in their midst, but these ring-tails were even closer and far more numerous-a superabundance of lemur-watching.

As we progressed from the open area by the fish farming lake into the trails of the forest itself, there were more ring-tailed lemurs-everywhere. Rarely did the span of a minute go by where they were out of sight. We saw a multitude of different individuals running along the ground, sitting on rocks grooming their tails, moving high in the canopy half-obscured by tree branches (many of them with babies visible on their bellies or backs), gorging on the fruits of the chinaberry, and generally going about their activities of daily living. It was amazing. It reminded me of Ranomafana, a forest full of lemurs, but more condensed in every aspect-a smaller area, with many, many more lemur individuals, and all from the same species. The population density was almost like that of humans on the streets of a mid-sized American town-around every corner in the trail, there were a few new individuals. The sensation that we were walking through a settlement, a community, a vibrant living space, of another species was very strong. It also happened to be accurate: ring-tailed lemur groups generally range from 6 to 24 individuals in size, and groups have been observed staying in the same area for over 30 years. Furthermore, those groups, although territorial (the females are dominant, and fight each other to determine the in-group “pecking order” as well as warding off other groups) can be packed in quite closely. In optimal habitat, population densities as high as 600 ring-tailed lemurs per square kilometer have been recorded. And Anja, as it happens, is the most optimal habitat for the species there is, judging by population numbers. As we walked, Mamy told us more about of Anja Community Reserve and its lemurs. He led off with perhaps the most amazing fact: the reserve, only encompassing three mountains and the forest around them, was home to over 400 ring-tailed lemurs! That was quite possibly about the same number (it’s uncertain) as all the greater bamboo lemurs in the world, and spoke well of Anja habitat’s high carrying capacity for lemurs and complete freedom from negative human pressures, like hunting or capturing for the pet trade. (The illegal pet trade is a major problem for ring-tailed lemurs, and one of the reasons the species listed by the IUCN as “near threatened”). Mamy told us that the lemurs had only three predators in the reserve: hawks, the giant Madagascar boa (sadly, we saw none of these massive snakes, as they were hibernating), and the fossa.

The reserve had once been government-administered, but was handed over to an association of citizens from six surrounding villages in 2001, and had been entirely community-administered since then. The original few who had supported the establishment of a community reserve included our guide’s father, and Mamy had been raised in conservationist ethics. He related the touching story of himself and Clementine. Mamy said that as a small child, in less enlightened times, he had had a pet ring-tailed lemur, Clementine, captured from the wild and fed on fruit, and had loved her dearly. His father, striving for a conservation-driven future for the local lemurs, said that Clementine must be returned to the forest, so as not to set a bad example of taking lemurs from the wild for pets. Young Mamy had cried when the day of parting came, but there was a bright side: Clementine successfully integrated with a local lemur group (very rare for ex-pets of any species) and he regularly saw her, as a wild animal, in the forest for years. When he grew to adulthood and became a guide, he was able to point out Clementine to several tourist groups, until her natural life sadly reached its close. Mamy dates the habituation of the local ring-tails from Clementine’s reintroduction. Before the reserve, when they had been hunted and trapped, the lemurs were understandably shy and fled at the sight of a human. Now, starting with Clementine’s adopted group, their “flight distance” began to decrease, eventually reaching the present very low level. Mamy said that he believes Clementine “told” the others, in the nonverbal communication of lemurs, that at least some humans were not to be feared. As there have been many previously recorded instances of individual wild primates spreading useful knowledge in their group (e.g. macaques in Japan learning from one bright spark how to wash their food before eating it, and gorillas in Uganda learning how to take apart snares in their territory from a juvenile who had watched rangers) I see no reason to doubt his conclusion.

Mamy also shared the story of a problem that had beset the reserve in its early days. Today, Anja has only one lemur species-the ring-tails-in comparison to Kianjavato’s nine and Ranomafana’s twelve. Once, it had had a second, a few dozen or so Eulemur fulvus, brown lemurs, one of the most common and widespread species in Madagascar. However, they had eventually grown “crazy,” out of control, possibly due to incautious feeding by unscrupulous actors in the past. The brown lemur group changed its behavior, became more aggressive, and even killed and ate a ring-tailed lemur baby. When they starting biting tourists, something had to give: they were a threat to the viability of conservation as a source of the locals’ livelihood. They were all humanely captured and relocated to the zoo in Antananarivo (I didn’t get which one, but presumably the Tsimbazaza Zoo, Madagascar’s finest). It was sad that they had had to be removed, but definitely on the positive side of possible outcomes for that kind of human-wildlife conflict.

As we walked deeper into the forest, another amazing species was much in evidence-Furcifer oustaleti, Oustalet’s giant chameleon, one of the two largest chameleon species in the world. We saw six different individuals, ranging in coloration from gray to green to yellow. For some of them, our two animal spotters held out insects on the end of sticks, and we saw the chameleons’ great long spring-loaded tongue unfold to snatch it back into their mouths. Mamy’s knowledge of the chameleons’ ecology was impressive: he told us that the males were larger than the females, and that the females only lived for about three years or so in comparison to the males’ five or seven. This was because the females had an immense quantity of eggs (the KAFS herpetological guide lists the record for the species at 61!) and their bodies could not long support the strain. Mamy also added that for the first few months of the hatchlings’ life, they were often eaten by their own parents, who perhaps mistook them for a smaller chameleon species, Brookesia sp. When they grew older, they were recognized as conspecifics and spared.

We walked further, ascending through the trees and up the slopes before the Three Sisters, climbing up steep, smooth rock faces and threading through a landscape of giant boulders, at one point using a rope to descend from one to another. In the USA, I would have said glacial erratics, but Madagascar hasn’t been glaciated for millions of years: these boulders were fallen rock, the residue of years of weathering and slow-motion crumbling of the great mountains above us. On one particular wide, flat, sunny rock, we sat down and took a break for a while, watching black kites circle lazily above us and soaking in the panoramic landscape of villages, fish farm, lemur-filled forest, boulders, rock faces, and mountain peaks around us. Mamy pointed out some tiny-seeming caves up at the top of one of the Sisters, had us focus in on one, and told us that it was the tomb of his great-grandfather, a Betsileo royal of the 1800s, King Samuel Ratsiomando. He said that as a Betsileo royal, of the Samuelson family, his mountain tomb had already been selected, and was visible from where we sat, but he was bound by custom not to reveal it. We learned that King Samuel had presided over a cultural shift in the funerary traditions of the Betsileo in the Anja area. It had been the tradition to bury the dead “in the bellies of the people,” but the people at that time came to the king and wanted it changed, on the basis that under this system the beloved dead eventually became excrement. Now, it was the tradition to sacrifice a zebu to please the ancestors, and to lay the bones to rest high in the mountains, in tombs of cave and stone, to watch over their descendants “like a second god.”

After we left that boulder, when continuing up the mountain, we saw one of those recent tombs (pictured), only two months old, with flowers and sacrificial zebu skulls atop the rocks that filled in the entrance. (I’d also like to note at this point that I made sure with Mamy that it was culturally appropriate and sufficiently respectful to write about and photograph Betsileo funeral traditions, historical and modern, and he replied that it was). The glimpse into the funerary traditions and lore of the Betsileo of the Anja region was an absolutely fascinating cultural experience, and added a new dimension to the Anja Community Reserve. Beyond a superb piece of ring-tailed lemur habitat and a much-needed economic lifeline that helped support and develop the surrounding communities, it was a sacred space, a place where kings were laid to rest, a place of tradition, history, and the stillness of ancient graves.

We ate lunch in a little rocky col between two of the Three Sisters, and then made our way back down through the forest by a different trail, which took us through a few great cave-like hollows between fallen boulders. On our way out of the reserve, we saw another group of ring-tailed lemurs, these ones atop another massive fallen-rock boulder, this one at the very edge of the reserve, at the boundary with the surrounding agricultural lands. We ascended the boulder ourselves, and shared the top with them for a while, watching them groom themselves and each other and scamper around the stones, and eventually move into the nearby treetops. For a while, just as we were leaving, one lemur sat on the edge of the rock, watching a man leading his zebu below. That image, of the lemur on the rock watching the cattle, and beside that the vegetable gardens, and the rice paddies beyond that, and the road and village in the background, seemed to encapsulate the beautiful harmony that typified the Anja Community Reserve. I was filled with a deep happiness at the sight, and all that it meant. The lemurs, by their mere presence, are attracting tourists and making money that bettered the lives of the humans, and the humans were in turn abiding by a conservation ethic that preserved the habitat and safety of the lemurs. This truly is the dream for conservationists in the Anthropocene: to create multifunctional living landscapes in which both humans and wildlife could thrive, mutually interdependent and supportive. I shall always remember Anja Community Reserve as a beautiful example of how such things should be done.

We stayed that night in the Hotel Petit Bouffe in Fianarantsoa, one of Madagascar’s larger cities, also in the Central Plateau region. The food was superb, and we all ordered multiple entrees-I had an excellent four-cheese pizza as well as potato croquettes. Added to that feast-like meal, showering and sleeping in a soft, be-sheeted bed (and sleeping in the next morning, to boot!) rendered the Hotel Petit Bouffe experience amazingly luxurious. I wholeheartedly recommend it to any visitors to Fianarantsoa. As I told the nearby hoteliers and staff after dinner, “Mafinatra be ny hotely” (The hotel is magnificent). We also had a nice encounter when withdrawing money from a local ATM, with a local man who seemed amazed to see Americans in the flesh. He had excellent English, and he said that he had thought of Americans as grim action heroes, like in the movies, but that we were “so peaceful, and joyful!” We were indeed. The weekend refreshed and inspired us all, priming us nicely for the next few weeks of fieldwork at KAFS.

A Workweek at KAFS: Collecting Data, Teaching English, Planting Trees

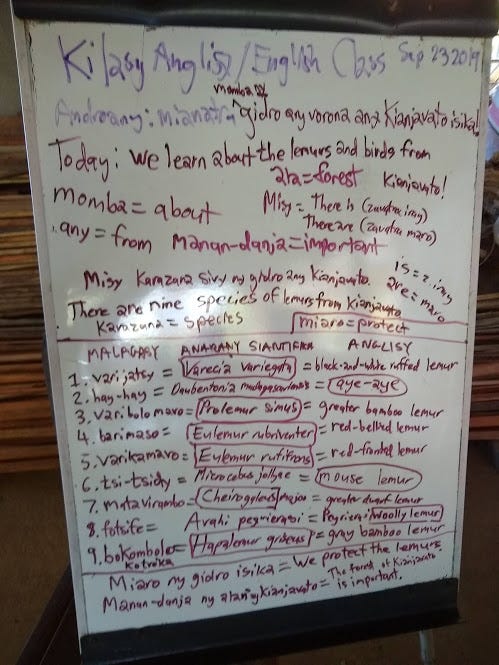

On Monday morning, I joined the compost team with Nelson, chopping up more roadside shrubs to serve as the organic matter base for future seedlings’ growth matrix. That afternoon, I taught perhaps my most influential English lesson yet: a combined language and biology lesson about the nine lemur species of Kianjavato Commune. I started out by teaching the sentence “Misy karazany sivy ny gidro any Kianjavato” (There are nine lemur species from Kianjavato) and then drew up a nine-row, three-column grid, containing the English, Malagasy, and scientific names for each of the nine species. For example, varibolomavo in Malagasy is the same animal as “greater bamboo lemur” in English, and is known worldwide by the scientific name of Prolemur simus. Eulemur rubriventer, the red-bellied lemur, is borimaso in the local Malagasy dialect. Cheirogaleus major, the greater dwarf lemur, is matavirambo. Hapalemur griseus, the gray bamboo lemur (very secretive: although they live here, I haven’t seen any yet!) is bokombolo, or alternatively kitroka. For each species, I passed around KAFS’ copy of Lemurs of Madagascar, Conservation International’s authoritative guide to all lemurs, opened to that animal’s entry. I also flipped through the entire book, pointing out the immense variety of lemurs in existence, and repeated “Madagasikara fotsiny” (Madagascar only), attempting to convey the scope and variety of the country’s incredible endemic biological richness. My students-thirteen strong that day-were fascinated, and I was eventually asked to leave the whiteboard up for a few days so more staff members could get a look at it. We also learned sentences like “Manan-danja ny ala ny Kianjavato,” (The forests of Kianjavato are important), “Miaro ny gidro isika” (We protect the lemurs) and “Miaro ary mianatra momba ny varibolomavo isika” (We protect and learn about the Prolemur simus). I profoundly hope that my humble efforts will help spread the word of the global importance and ecological value of my Malagasy colleagues’ homeland, and I feel honored to be able to share some information about my students’ natural heritage.

On Tuesday, I was privileged to rejoin the Prolemur simus team for a day, Reforestation having sufficient volunteers for the daily tasks. It felt great to be back on the trails of Sangasanga for a day, data-collection notebook in hand, adding a small piece to humanity’s store of information about a critically endangered primate. That day, I joined Rasolo and Delphin in following Hopper of the East Two group. (As a side note, there have been some very exciting positive developments in the Prolemur simus populations since I worked with them, but that falls under the heading of confidential information, which MBP must needs disseminate in an orderly fashion. Perhaps I will be able to write about it, or share MBP’s take on it, in months to come). I can say that it was absolutely awesome to be among Prolemur simus again, watching the group go through their morning rhythm of resting in the trees, eating jackfruit, moving to a bamboo grove, and eating bamboo leaves. In this last stage, the three of us ended up in the center of the group, with lemurs all around us. Pictured is Juvenile Female, staring at me from a temporary perch on a bamboo stalk.

Early in the follow, I also got a close look at a group of Eulemur rufifrons, who, as is their wont in the early mornings, were hanging around with the varibolomavo. This “rufie” (a male, by his facial coloration) was curious, and spent some time very clearly looking at me, wondering no doubt what on earth was the business of these strange creatures. E. rufifrons are so closely related to several other members of their genus, such as E. fulvus and E. rufus, that they weren’t considered their own species until relatively recently. Lemurs of Madagascar reports that they have relatively low intraspecies aggression rates, primarily eat fruit, and that all the babies are born with the male facial coloration, with females losing it later. They are one of the more common lemurs in Madagascar, although they are threatened across their reign by hunting for food and habitat destruction for slash-and-burn agriculture (tavy).

At the end of the follow, the three of us shared a jackfruit, from the same jackfruit tree that the lemurs had been feeding from earlier. Delphin climbed the tree to knock down the jackfruit, and I caught it and donated my knife to serve as a tool to cut it apart. We shared the jackfruit on the walk back to Kianjavato. It was delicious: juicy and rather pineapple-like, but with, to my mind, a more appealing texture. It felt like sharing a meal, removed in time only by a few hours, with the varibolomavo I loved.

That afternoon, only one student was available for my aye-aye team English class, so I gave him a one-on-one in-depth version of the “Lemur Species of Kianjavato” class I taught the day before.

On Wednesday morning, I was the volunteer for a planting event on a hill very near the main town of Kianjavato, based out of the Kianjavato nursery. It was a hot day, and we were on a deforested hillside, so it was sweaty work: requests for water were many, and although I had brought two full water bottles in my backpack anticipating this eventuality, we soon ran out. One woman came up with a load of sugarcane on her back, and we all, volunteers, staff, and day laborers, paused to share the bounty. I gave my knife to Romuald to help split up a stalk of cane (which he did skillfully, in seconds) and then tried to eat the internal pith. The first few chews gave a welcome burst of sugary water, but a few more left an unyielding, chewy, fibrous substance with no taste or moisture whatsoever. I glanced around, worried that I would need to swallow down the whole thing, and then noticed most people were just sucking the sugar-water out of the cane and discarding the rest. Another little lesson for an inexperienced “vazaha” from northern climes: how to eat sugarcane.

My English class Wednesday afternoon started with an extension of the natural-world theme I began on Monday: learning the names of a few common local birds. As bird names in Malagasy vary substantially by region (as do lemur names, but I had more information beforehand on them), it was a very two-way, participatory lesson, in which I learned the Malagasy names for certain birds in the bird guide even as my students learned the English names. (I didn’t teach the scientific names for the birds. Unlike mammals, there is an international system for standardizing bird names in English, so an American Robin or a Cuckoo-Roller will go by the same common name in all English-speaking avian circles, while Hapalemur griseus is known variably as the gray bamboo lemur or the gray gentle lemur). I learned that the local name from the Crested Drongo (a beautiful passerine, common at KAFS, easily identified as the only all-black bird in Madagascar) is “railovy,” or “king/queen’s bird,” as it had been a symbol of the old Malagasy monarchy, perhaps due to the crown-like tuft of feathers on its head. This led into a discussion of the terms “king” and “queen” in English (Malagasy has one gender-neutral word for ruler: “Mpanjaka”) and eventually into an impromptu discourse on past, present, and future tenses for adjectives and verbs. I felt I explained it rather well, but felt compelled to apologize “Miala tsiny, anglisy sarotra” (Sorry, English is difficult) when we hit the confusion of distinct past-tense forms for each word, like “slept,” “ate,” and “saw.” When teaching English, I have always tried to minimize the grammatical nuances in favor of ensuring retention of the basics that will make a person understood: vocabulary and sentence structure. The approach, I feel, is paying off: I have been very impressed with the dedication, tenacity, and excellent memory of all of my students.

As with all Thursdays on the reforestation team, our primary task on the 26th of September was the nursery check, stopping in at all of MBP’s 16 nurseries along the main road of Kianjavato Commune. We delivered supplies, from brooms to buckets, and I wrote down seedling counts, requests for new supplies, and orders for compost, sand, and red soil for the rest of the week. It was a pleasant task, made even more amenable by the spell of lovely weather we’ve been getting here at KAFS. Since the September 23rd equinox (the fall equinox for the northern hemisphere, as it’s now tilting slightly away from the sun, but the spring equinox down here in the southern hemisphere, as we’re now tilting slightly towards the sun), we’ve gotten a spell of warm, sunny days. The natural world responds, too-for example, the dwarf lemurs (Cheirogaleus spp.) are coming out of hibernation, and one volunteer saw one at the edge of camp a few days ago. It may be confirmation bias, but also I feel I’m beginning to notice more insect activity, particularly butterflies, as the season changes. It’s certainly not anywhere near as sharp a discontinuity as I’m used to in New England, but the temperature difference is definitely there. Until recently, during the Malagasy winter (which felt to me rather like a Maine summer), I wore my hoodie in the mornings, but now I’ve ditched the hoodie and am wearing short-sleeved shirts much more often. The difference between Maine summer and Madagascar winter was slight, but I suspect that the difference between Madagascar spring and Maine fall will be much greater. It’ll be interesting to experience the rapid shift between seasons when I fly home in mid-October.

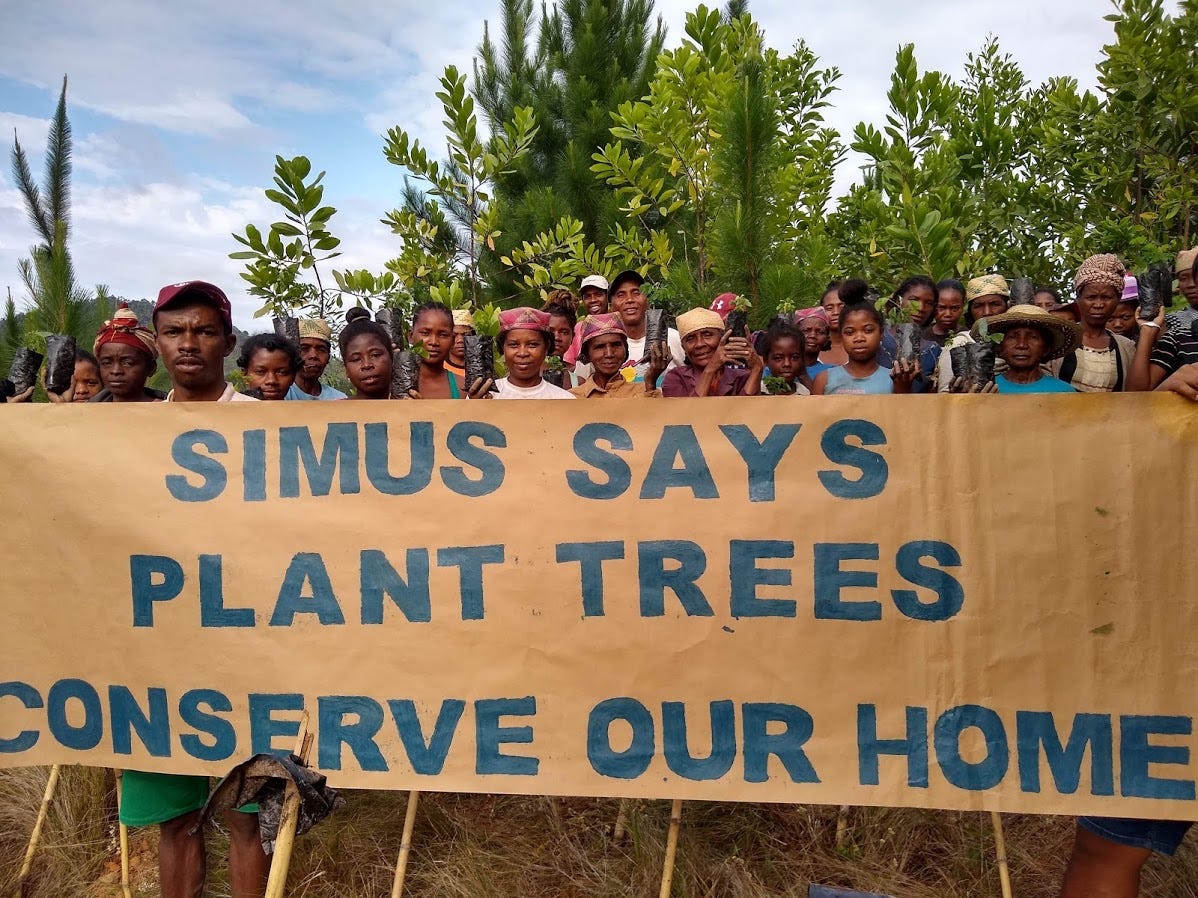

On Friday, September 27th, the Reforestation team went into overdrive for the Simus Says event. Both a pun on “Simon Says” and an expression of what Prolemur simus might say if it could speak and understand the threats to its habitat, Simus Says is a yearly day of en-masse planting events. Normally, we have two planting events per day on our weekly planting days, Wednesdays and Fridays, but on Simus Says we had five, spread across the Kianjavato Commune and totaling 13,000 trees! I went with Nelson (he of the compost squad) and Ismael to a planting event based out of Vohipotsy, one of the four “distant nurseries” not accessible by the main road. We walked for perhaps an hour, starting from the Vatovavy nursery entrance, the same trails on which I had learned, a few weeks ago, the true difficulty of carrying a basketful of seedlings on one’s head. It was a lovely event-I took an array of pictures of the event for MBP (including the one above), did my regular planting-volunteer duties of entering everybody’s names and ID card numbers and distributing the pay, helped with planting the trees, and hung out with the other planters, sharing songs and taking pictures of individuals for them to admire on request. At many MBP plantings, including this one, the workforce mainly consists of members of the local Single Mothers’ Club, who often bring their kids to the planting and chat and sing gaily as they work. These women have invariably been kind, hardworking, and friendly in my experience, and their presence is another example of how the Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership is a wise and farsighted organization, with a profound human and social dimension to every aspect of their conservation work. First of all, of course, it is simply a good and decent thing to do to give these often-marginalized people a safe place to work and a way provide for their kids. Longer-term, it is almost tautologically a good thing for a society to invest in mothers, especially single mothers. As a multitude of studies have found, women with kids are more likely than men (with or without kids) to use the resources they have in long-term investments, like education and healthcare, that lead to better things for their children. Offering the local single moms, safe, stable jobs that they could bring their kids to (Single Mothers’ Club members work half-day shifts at the nurseries on non-planting days) kicks off a great virtuous cycle. Women who can earn money on their own can support themselves on their own without needing a man for economic support, which means they generally have fewer kids, which means they can invest time, care, attention, and money in the kids they already have, which leads to a better educated and healthier next generation. And, of course, fewer kids mean that fewer acres of land are needed to feed them, always an important consideration in a subsistence-agriculture economy with a fast-growing population like Madagascar. The presence of MBP’s Single Mothers Club initiative will likely be paying dividends for the Kianjavato Commune for decades to come.

On the walk back from Vohipotsy to the road, I saw stooping figures in a river, by the side of a hacked-open hillside, at the other end of a long valley. I asked Ismael what they were doing, and he said that they were mining and panning for precious stones I gasped-I had read about this, but it was the first time I had seen it in reality. Madagascar is as rich in precious stones as it is in precious wildlife species, and in recent years, many Madagascans have sought to augment their income by obtaining them and selling them, often at pitifully low prices, to middlemen who then sell them for great amounts in Asian, European, and American gem and crystal markets. For more on this issue, and how to ensure that any gem purchases are from ethical sources, check out National Geographic’s and the Guardian’s articles on it.

After returning to KAFS and relaxing for a while, I spent the afternoon and evening entering the planting data for the day-all 13,000 trees-while my teammates, Dakota and Dana, labored long on inventorying all Reforestation equipment and preparing the budget for the next week. On breaks, I read about the recent UN Summit, and was reminded of the global context for our work. First, I was incredibly proud to read the text of Governor Janet Mills’ speech before the UN saying that Maine would not wait to act on climate change, but was committed to using its forested land, windy and sunny shores, and entrepreneurial people to become carbon neutral by 2045. I also read of the importance that nature-based solutions to climate change-like the reforestation work that MBP was doing right now-had been accorded at the summit. Norway had struck a deal with Gabon in which the Scandinavian kingdom would pay the Central African nation up to $150 million over 10 years, paying $10 for each certified ton of climate change-causing carbon dioxide sequestered by Gabonese rainforest and protected from deforestation and degradation. Gabon is 88% forest cover, one of the few African countries to maintain most of its primary rainforest, and its government is now committing to preserve 98% of its existing rainforest from logging. Although much implementation remains, this is a historically spectacular, very big deal! Furthermore, five renowned conservation groups, Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC), Rainforest Foundation Norway (RFN), Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), World Resources Institute (WR), and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), launched the Forests for Life Partnership. This new initiative, with $50 million in funding already lined up and $200 million more on the way, aims to prevent the degradation of 1 billion hectares of planet Earth’s top-quality carbon-sequestering forests, with seven focal regions including the Amazon, the Congo Basin, New Guinea, the northern boreal forest zone stretching across Russia and Canada, Mesoamerica, South and Southeast Asia, and, yes, Madagascar! MBP isn’t a part of the Forests for Life Partnership, but it’s quietly doing exactly the kind of work these heavyweights are calling for, and doing it passionately, efficiently, and well. Along the way to Vohipotsy, I saw wide groves planted by MBP five years ago, now twenty- and thirty-foot trees sequestering carbon in their woody bodies and providing shade, shelter, and connectivity to local species. I feel incredibly proud of my comrades, from Madagascar and around the world, in MBP and in a thousand other organizations, who are working every day to stabilize our planet’s climate and protect its ecosystems.