What Skeptical Climate Voters Need to Know About Kamala Harris

Clearing up confusion about the Biden-Harris administration's climate record

In the 2000 U.S. presidential election, George W. Bush beat Al Gore by 537 votes. 8 years of federal power, a couple catastrophic wars, and nearly a decade of lost climate progress were decided by fewer people than my high school graduating class.

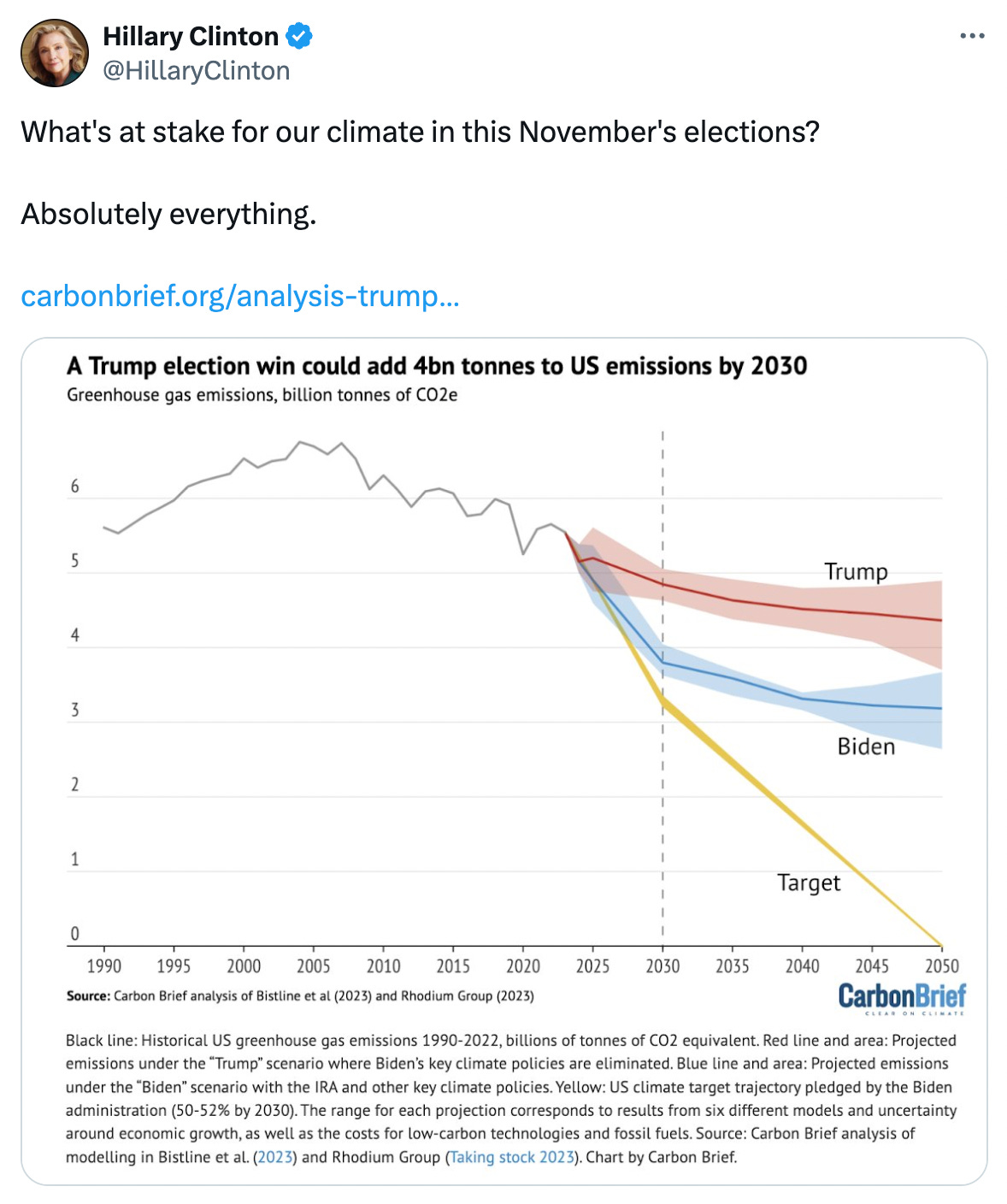

This year, as in 2000, Americans face a similarly stark difference between candidates when it comes to climate policy. If Kamala Harris is elected, the country has a real shot at reaching the emissions targets outlined in the Paris Agreement. If Donald Trump is elected, the country is likely to emit 50% more greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, a difference of more than a billion tons of emissions per year, according to projections by Carbon Brief.

Despite this difference, some climate advocates aren’t fully supportive of Harris. I know this because whenever I write about the administration’s climate policies or the upcoming election I receive emails and comments from Biden-Harris skeptics.

Last week, I polled my audience of 15,000 readers. 91% of readers said they plan to vote for Harris. 4% said they plan to vote for a third-party candidate. 2% don’t plan to vote. 1% are still undecided. Another 1% plan to vote for Trump.

My informal poll understates the risk of low climate voter turnout. The Environmental Voter Project has identified millions of voters who rank climate as their number one issue who don’t consistently vote or turn out at all. Many of them reside in swing states.

In this article, I want to share some of the arguments I’ve heard for why climate voters aren’t supporting Harris and make my case—backed up by deep reporting and research—for why they should.

I’ve written about the Biden-Harris administration’s smart climate policies and impressive progress. This article won’t re-cover that territory, but instead respond to the critiques of the administration’s climate record that I’ve heard.

I’m writing this in hopes that I can convince a few people to vote for Harris. But I’m also writing this for those who are already passionately supporting her campaign.

The real work of democracy isn’t writing newsletters; it’s talking to and listening to our friends, family and neighbors. In his book, The Persuaders, Anand Giridharadas argues that public opinion changes one conversation at a time. Political persuasion is inherently unscalable work. I hope this article can help support some of that work and inspire new conversations.

Record fossil fuel production

The critique I hear most often from climate voters is that Biden and Harris have led the country in an era of skyrocketing fossil fuel production. As one reader recently wrote me, “[Oil] production is at record levels, and the industry shows no sign of letting up.”

Harris hasn’t shied away from this fact either. In her debate with Trump, she said, “We have had the largest increase in domestic oil production in history because of an approach that recognizes that we cannot over-rely on foreign oil.”

The data supports this claim. Oil production is up 20% since 2020. America is now the world’s largest producer of oil. The country will export more liquified natural gas (LNG) than any other this year. To say that oil and gas production is hitting records almost understates the data. Ever since the fracking boom began, America’s fossil fuel production has surged like never before.

This surge in production will have enormous consequences. Harris alluded to the geopolitical implications during the debate, but said nothing of the consequences for the climate to the frustration of many climate activists.

Oil and gas are the primary drivers of climate change globally. The only way to cut emissions is ultimately to wean ourselves off fossil fuels.

But in order to assess the Biden-Harris administration, it’s essential to understand the causes of growing fossil fuel production.

How much can a president influence production?

If you ask Biden, Harris, or Trump, who’s responsible for the latest oil and gas boom, they’ll all point to themselves. But in reality none of them are. Oil and gas production depends on myriad factors that go far beyond the power of a president.

Take just one of those examples: drilling technology. Much of America’s recent growth in production can be attributed to fracking technology that dramatically increased the productivity of each well. Companies are drilling deeper into the Earth and extracting more oil and gas at each site. As Shelly Webb wrote last year for E&E News:

In the Permian Basin alone, the average lateral length of horizontal wells increased to more than 10,000 feet in the first nine months of 2022, compared to less than 4,000 feet in 2010…

The number of barrels of oil produced per foot of drilling has increased 200 percent since 2014, with much of that progress coming in the last three years.

Even if the federal government hadn’t issued a single lease or permit in the last three years, oil and gas production would have risen. In fact, oil’s growth over the last decade coincided with a decline in federal leasing and permitting, according to an analysis by Resources for the Future.

Without Congress, the president can only influence production that happens on federal land. Banning oil and gas drilling on all land outright would be unconstitutional and immediately reversed by the Supreme Court. But 90% of the country’s oil and gas production happens on private and state land.

Trump has said he wants to be a dictator on day one. He’s told voters this could be the last election. But right now, America is a democracy with three branches; and just as that limits a president’s abuse of power, it also limits their ability to control oil and gas production.

Look at the history of oil production and you’ll see more intuitive cracks in the logic of this first critique. Between 2000 and 2008, oil production fell significantly. If Biden and Harris are climate villains because of the recent growth in oil production, the same logic suggests that George W. Bush is a climate hero because of the decline in oil production during his presidency. (Make no mistake, reader: Bush was no climate hero).

Clearly, we have to look at more than just production numbers to evaluate a president’s climate policies.

The Biden-Harris administration’s great betrayal

A president can’t force companies to drill or magically boost well productivity overnight, but he or she can lease federal land and permit projects. For many climate activists this is where the Biden-Harris administration committed their greatest sins.

On the 2020 campaign trail, Biden promised to ban oil and gas drilling on public lands. He didn’t leave any room for misinterpretation. At a campaign event in New Hampshire, he said, “No more drilling on federal lands. Period. Period. Period. Period.”

But through his first two years, Biden opened up 324,000 acres of public land for oil and gas drilling. To many, this was proof that the President was like any other politician—willing to say whatever it takes to get elected and quick to break promises. It’s proof that when Harris says she’ll act on climate, she’s probably lying too.

But the administration’s oil and gas leasing policies have a complicated history—one that’s essential to understand when assessing Biden and Harris’ climate record.

Biden and Harris vs. the federal court system

One week after taking office, Biden followed through on his campaign promise when he signed an executive order instructing the Interior Department to pause all federal oil and gas leases. He soon learned the limits of a president’s power in a country with three branches of government and a federal court system full of Republican-nominated judges.

Republican-led states sued the administration over its leasing policy and within five months, a Trump-appointed federal judge forced the Interior Department to resume leasing federal land to oil and gas companies.

“There’s a gap between what some advocates want the president to do, and what he can actually do,” Michael Gerrard, a Columbia University climate legal expert told The New York Times last year.

Still the administration has found ways of limiting the amount of land it leases. The 324,000 acres leased in 2021 and 2022 sounds like a lot until you compare it to the 2.4 million acres the Trump administration leased in its first two years in office.

Some climate activists point out that when it comes to permitting, the Biden-Harris administration looks far worse. Through their first three years, administration issued 9,779 oil and gas permits on public land compared to Trump’s 9,982 permits.

But again, the administration’s hands were tied by the American legal system. As The Washington Post’s Maxine Joselow wrote in August:

Interior cannot legally reject an oil company’s application for a permit to drill on public lands after it has already won those acres in an auction.

The Interior Department was forced to lease land and then forced to approve permits on both the land they leased and past administrations leases.

“The fact is that President Biden has followed the rule of law in this country, and the rule of law says that if you have already given a lease to a fossil fuel company, you have to give a permit,” Leah Stokes, a professor of environmental politics at the University of California at Santa Barbara, told The Washington Post.

The Willow climate bomb

Few decisions that the Biden-Harris administration made enraged climate activists more than their approval of the Willow project, an $8 billion oil drilling site on federal land in Alaska.

According to the administration’s own estimates, the oil extracted from the site over 30 years will result in 254 million tons of carbon emissions. Following a massive social media campaign, millions of Americans asked the administration to block the project. But they approved it anyway.

It’s hard to overstate what a disaster this was for the administration’s public approval among climate voters. As The New York Times reported at the time:

A March poll from Data for Progress, a liberal research group, saw a 13 percent drop Mr. Biden’s approval ratings when it came to his climate agenda among voters aged 18 to 29 in the aftermath of the Willow decision.

In approving Willow, the administration had the same goal that Harris had during the last debate when she talked up fracking: It was trying to signal to swing voters that—despite all the climate policies it was passing—it wasn’t pursuing a radical agenda.

Reasonable people can debate the merits of this strategy.

The climate crisis undoubtedly requires radical action. There is no moderate path from billions of tons of emissions per year to zero, no chill way of remaking the physical world, and replacing trillions of dollars of infrastructure. The chill pathway leads to a hot, wild, and unstable world.

But in a democracy, climate policy requires public approval. And today, most Americans want policy that isn’t aligned with what experts say is needed to avoid climate disaster. As Heatmap’s Robinson Meyer pointed out recently, two-thirds of Americans want a mix of fossil fuels and renewables, according to polling by Pew Research Center.

In order to win elections and continue passing climate policies, Democrats believe they need to make compromises. And barring big changes to the Supreme Court, Electoral College or voter preferences, I think they’re right.

Weighing the good and the bad

One of the narratives that emerged from the Willow debate was that the Biden administration’s fossil fuel approvals, permits, and leases were cancelling out their other climate policies.

“[Biden] takes one step forward with the I.R.A., and two steps back with the Willow project,” Jamaal Bowman, a progressive House Representative from New York, told the New York Times following the approval.

This narrative was meant to put pressure on the administration. But it ultimately misled voters.

When the oil extracted from the Willow project is consumed it will emit 254 million tons of carbon. But that’s not the true climate impact of the project. A rigorous analysis has to consider what climate modelers and economists call “leakage.” As The Washington Post’s Shannon Osaka reported last year:

“There’s plenty of oil and gas in the world,” said Samantha Gross, director of the energy security and climate initiative at the Brookings Institution. “If we don’t produce that oil, and there’s still demand for it, someone else will.”

In economics-speak, this is known as “leakage.” The idea is that if there is a decrease in fossil fuel supply — through a ban on drilling in one country, for example — fossil fuel prices will rise, and then another company will expand drilling elsewhere in the world. Simple supply and demand.

After accounting for this leakage, the additional emissions from the Willow Project drop to 70 million tons. That’s a lot more than zero, and in a world where every fraction of a degree of warming matters, that’s a problem. (Ideal climate policy cuts demand and supply at the same time).

But how does that 70 million tons of climate impact compare to the emissions reductions that are expected from the Biden administration’s other policies?

Over the next 30 years, the IRA is expected to cut emissions by 21 billion tons. The administration’s tailpipe rules that are expected to accelerate adoption of EVs are expected to cut 7.2 billion tons over that period. The power plant rules finalized earlier this year will wipe out another 1.38 billion tons.

And those are just the policies that got the most media attention. An executive order aimed at improving the energy efficiency of water heaters will cut 2.5 billion tons. Another order aimed at LED lighting will cut another 222 million tons.

Those five policies—which aren’t a comprehensive list of the administration’s climate actions—will result in a combined 32.3 billion tons of emissions reductions over 30 years.

“One step forward and two steps backwards” has a nice ring to it. But the actual numbers suggest a different picture entirely. In passing those five policies, the administration took 461 steps forward. With its Willow approval, it took one step back.

“I’m voting for target”

Earlier this year, Hillary Clinton tweeted out a chart from Carbon Brief’s analysis that I mentioned at the beginning of this story. The analysis showed that the policies passed by the Biden-Harris administration would lead to emission reductions of 43% by 2030, compared to 28% under a Trump administration.

Immediately people began sharing Clinton’s tweet with captions like “How can I vote for ‘Target.’” For many people, the chart put numbers to an intuitive sense that the administration’s climate policies weren’t perfect; they weren’t enough to cut emissions in half by 2030; and they weren’t enough to get us to zero emissions by 2050.

I fear this belief will keep many climate voters home in November. The feeling—the vibe, if you will—extends beyond the issue of climate change. Despair and apathy have become central emotions in our democracy.

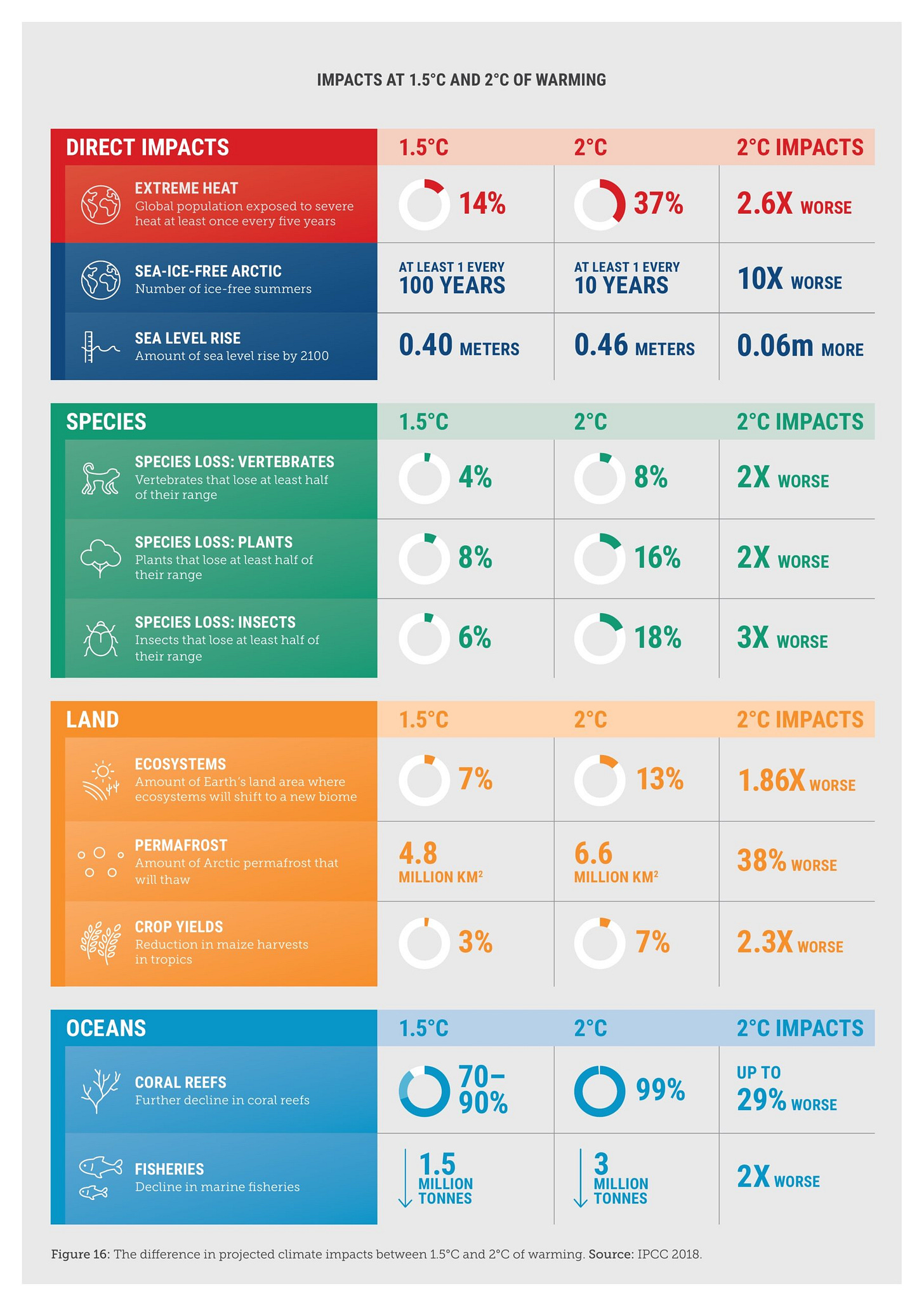

But progress depends on each of us fighting the urge to allow despair to slip towards nihilism. The difference of a billion tons of annual emissions might sound as meaningless as the difference of 0.1 degrees of warming. But the consequences—the higher risks of natural disasters and droughts, the increased food insecurity, the species losses, the suffering—are real, as the IPCC has painstakingly documented.

Policies passed by the next president will significantly influence how much our world warms up. An IRA 2.0 bill under Harris that continues America’s climate progress will result in less warming. An IRA repeal under Trump will result in more.

The Biden-Harris administration has made much climate progress already. The billions of tons of emissions reductions made possible by their policies give the country a chance of reaching the Paris Agreement targets.

The country can continue to make progress. But in order to do it, we must elect Kamala Harris in November.